|

Short accounts by Tring residents of

aspects of their lives and of past events,

collected and preserved by local historian Jill Fowler.

――――♦――――

|

CONTENTS

TRING AT WAR 1914-1918, by John Bowman

THE COUNCIL, by Bob Grace

TRING FIRE SERVICE

(author unknown)

ALL BECAUSE THE FIRE

BRIGADE WASN'T THERE? by Denis Aldrige

THE FIRE BRIGADE, by

Jill Fowler

THE

WRITINGS OF FRANK JOHN BLY,

antiques dealer

EARLY DAYS OF THE WAR, by Doris Miller

MEMORIES OF A TRING EVACUEE,

by

Joyce Hollingworth

EMUS, TOBOGGANS,

FIREWOOD AND OLD TIN PLATES, by Ron Kitchener

AKEMAN STREET IN THE 30s AND 40s, by Doug

Sinclair

THREE GENERATIONS OF FARMERS IN TRING, by Stephanie Wells

MEDICINE IN TRING - A SHORT HISTORY, by Dr. D. F. E. Thallon

SEVENTY YEARS AGO, by

Dennis Aldridge

THE TRING ASSOCIATION

FOR THE PROSECUTION OF FELONS

THE CLUBS OF A HUNDRED

YEARS AGO, by Jill Fowler

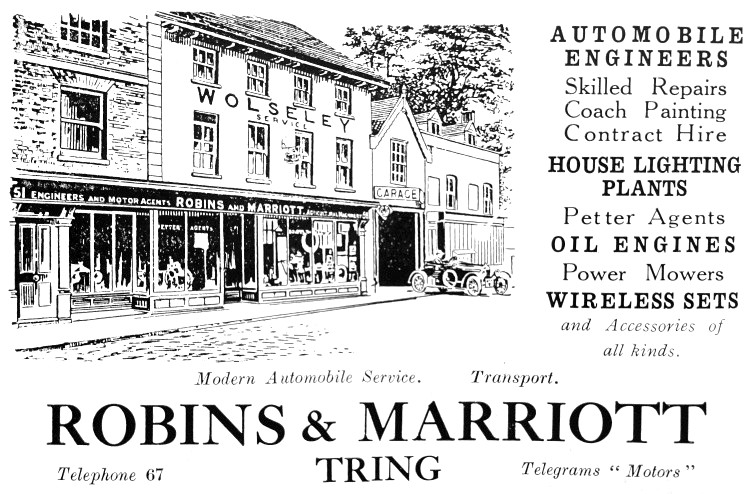

TRING AND THE MOTOR CAR,

by Jill Fowler

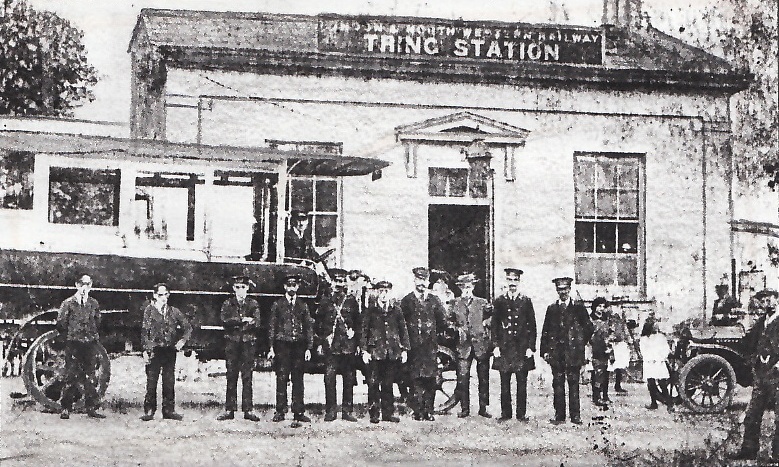

TRING STATION - TRUTH

AND HALF TRUTH, by Tim Amsden

MEMORIES OF TRING IN THE

THIRTIES, by Jerry Spencer

BORN IN THE

SAME YEAR AS THE QUEEN,

by Pam Cockerill

――――♦――――

TRING AT WAR 1914-1919

Researched and written by John Bowman.

August 1914: Reservists were reporting to their Naval and Army establishments,

and the Territorial Army mustered at their local drill halls.

The Territorials were primarily a home defence force of volunteers

who were requested to sign for service where required; the majority

volunteered at the outbreak of war.

Lord Kitchener, an outstanding military engineer and soldier, and well

known for his service in Egypt, The Sudan and South Africa, was appointed

Minister of War. He immediately asked for 100,000 volunteers to

supplement the small regular army, most of which was engaged in

France supporting the French and Belgians against the Kaiser’s army.

The 100,000 target was achieved in the first few days following the

proclamation. Preparations were then made for the recruitment of a

further 100,000 men.

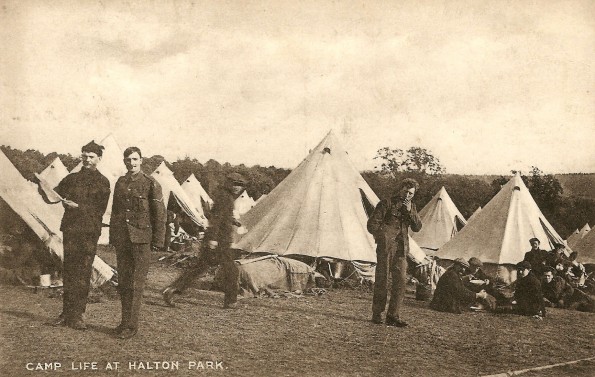

In September 1914, it was rumoured locally that a new Army Division

was to be formed at Halton Park, which had been offered to the crown

as a Rothschild contribution to the war effort. A tented camp was

erected on what is now the Halton Airfield and men began arriving

from the north-east, from Northumberland, Durham and

Yorkshire to form the new army’s 21st. Division.

Due to a very wet autumn, the tented camp was soon waterlogged and

the soldiers were out housed in any available accommodation. Three

thousand soldiers were billeted in Tring, mostly with local

householders.

The school in the High Street was commandeered. The pupils were

accommodated in various locations. The boys went to the Church House

and Market House/Hall. The girls went to the lecture hall in the

High Street Free Church, and the Western Hall, which was situated

where Stanley Gardens is now.

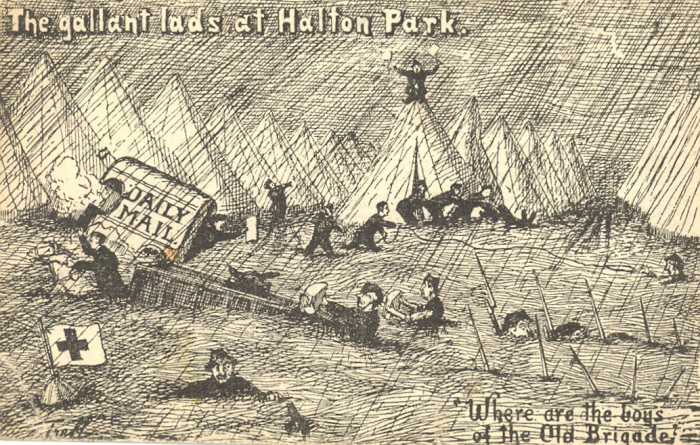

The ‘gallant lads at Halton Park’ in a

sea of mud.

The Victoria Hall and the Gravelly School became medical and

hospital accommodation, the infant pupils being housed in the

Sunday School Room of the Akeman Street Baptist Chapel. The YMCA

building, in the Tabernacle Yard, Akeman Street was opened as

writing and reading rooms for the soldiers. Bathing facilities were

installed in the Museum’s outbuildings.

A bathing parade.

The billeting rates paid for soldiers were quite generous for the

time and, no doubt, supplemented the income of the townspeople,

which was lost when so many of the population volunteered.

In November, it was reported that Arthur Wells who lived at

Tringford had been lost at sea. He was a stoker in the Royal

Navy, and had been recalled at the beginning of the war. He

was serving in HMS Aboukir, a cruiser. His Majesty’s

Ships, Aboukir, Cressy and Hogue were elderly ships of the “Battle”

class [Ed. – Cressy class] and all three were lost, torpedoed in

the North Sea, on the same day, 22nd September 1914. Reginald

Seabrook of Tring, a seaman, was serving on HMS Hogue when it was

sunk and he was picked up from the sea.

Together with sister

ships Aboukir and Cressy, HMS Hogue was torpedoed and

sunk in the North Sea by the German submarine U-9 on the 22nd September,

1914.

In total,

62 officers and 1,397 enlisted men were lost in this disastrous

engagement,

which revealed to a complacent Royal Navy the danger of submarine

warfare.

In Tring, various groups of ladies were knitting comforts for the

troops, scarves, gloves and balaclava helmets were welcomed by all

the troops in the trenches. The front had settled to a line

which was to stay until early 1918. The trench systems

throughout were an elaborate mishmash of deeply excavated trenches

in the Arras/Somme area, to built up defences in the flat coal

mining areas around Vimy/Lens/Bully and the Ypres salient, where

water would appear at two to three feet under the surface.

Large quantities of sandbags were needed for the defences.

Also wattle hurdles, chestnut paling and withy fascines. The

manufacture of these was a rural craft, a local industry. Of

course, the manufacture of sandbags was a commercial undertaking.

It is estimated that each division of 15,000 men would need over one

million bags a month.

The voluntary effort by women’s groups to make sandbags was

organised by a Miss Tyler who worked from North London as a

collecting point. The purchase of hessian was undertaken

locally, in the Home Counties. Women’s groups made the bags

measuring 33 inches long by 14 inches wide. By September 1914,

10,000 sandbags a day were dispatched to the front. The

collecting point in Tring was Hazely, a street in Tring, where Miss

Helen Brown and her helpers bundled the sacks for collection.

All costs for this enterprise were met by public subscription.

Every pound raised provided 60 bags.

A poem written by a soldier of 21st Division:

|

The boys from Halton Park

There are five and twenty thousand

Bold recruits who have made a start

To train to fight for their country

In this spacious Halton Park.

When they are trained and ready

To the front they will embark.

Then you will hear the people say

‘There’s the lads

from Halton Park’

And when Berlin is taken,

The Kaiser will remark

“Where did those fearnoughts come from?”

Why, of course, from Halton Park.

And when we come home victorious,

And each man has made his mark

Where will the honours go to?

Why,

the lads from Halton Park. |

Summer 1915: the district nurse,

Miss Girardet, has

resigned and is presently nursing at the military hospital on

Wandsworth Common. She has been thanked for her 17 years

service to the community. Miss Green has been appointed in her

place.

A cartoonist’s view of the Wandsworth

Military Hospital.

|

“Miss Girardet has been

here as a Staff Nurse since October, 1914. She is one of

the most capable nurses we have, and is generally loved

by all of us for her kindness and goodness to those

around her. She was trained at Westminster Hospital and

has been District Nursing since.” Fanny Clara

Girardet was later awarded Royal Red Cross Medal for her

wartime services. |

The 21st Division are now in France and have been in action around

Loos/La Bassée. Halton Camp is now the training facility for

the East Anglian area.

Gallipoli has been evacuated. A combined force of French and

British troops, have occupied Salonica and have moved into Thessaly

and Macedonia, in support of the retreating Serbian army. The

Kitchener battalions of the Oxford and Bucks Light Infantry are part

of the force. A number of local men are in these battalions.

The casualty lists are depressingly long. Almost every family,

locally has either lost a relative, or had news of one wounded or

taken prisoner.

The production of shells and ammunition is being co-ordinated by the

government. The shortage in 1915 was felt by our armies on the

Western Front, and is no doubt the main cause of our failure to

progress militarily.

1916: saw the National Service Act coming into operation. This

allowed the direction of the work force as required for the war

effort. Local tribunals were established, which allowed

exemption for men with large families, men and women who held

essential jobs and men running family businesses and farms.

The pronouncements of the tribunals were not always acceptable, and

recourse to an appeal board was often sought.

The shortage of food, due in part to the German submarine warfare is

having a serious effect on the population. The licensing laws

were changed, with pubs having restricted opening hours. These

restrictions remain virtually to the present day.

|

|

|

Field Marshal Lord Kitchener

(1850-1916) |

HMS Hampshire, a cruiser, was sunk north of Scapa Flow in the Orkney

Islands on June 5th 1916 [Ed. – Hampshire is believed to have struck a

mine laid by the German minelaying submarine U-75. She sank with

heavy loss of life]. She had on board, Lord Kitchener and

a delegation, which were on their way to Murmansk in Northern Russia

to meet the Russian Imperial Command. Lord Kitchener’s

body was never found. However, Able Seaman Stanley Collier,

one of the crew, was recovered from the sea and buried in the

military cemetery on the island of Hoy. He was a Tring man and

is commemorated on the Tring war memorial.

The Chiltern beech woods were being cut down to provide timber for

the trench systems in France. Three forestry engineer units

were at work in the area, one being from Australia. The

consumption of timber was so great at the front that a special port

facility was built on the river Seine, at Rouen, solely for the

handling of timber.

The meadows in the Vale of Aylesbury were in great demand for the

production of fodder for horses, many thousands of which were used

for transportation and supply by the Army, at home and in France.

At Paines End, just over the county boundary in Drayton Beauchamp

parish, the Royal Engineer (Signals) had established a small unit

engaged in radio communications. They were housed in tents and

a portable canvas hut. The lady in a cottage nearby was asked

if she could supply hot water for the soldiers’ ablutions. She

said she would, but that she had no fuel to heat the copper

in the outhouse. The next morning there was a visit from the

Bucks policeman from Aston Clinton. He asked if the family had

seen anybody passing with ‘wooding’ trolleys, as a quantity of

timber was missing from Pavis Wood. Later that day the estate

policeman came and asked the same question. Of course, the

woman denied having seen anybody passing. When she next went

to the outhouse, she found it was full of logs!

During 1916 the British and Commonwealth armies took over most of

the front extending from the Somme River to a point north of Ypres

where the remnants of the Belgian Army held the front to the Channel

coast. Preparations were made for a major attack to be made in

the area north and south of Albert, which we now know as the Somme

offensive. The battle raged for four months.

During this time many names were added to the Tring Roll of Honour,

many men were posted as missing, believed killed. On March

19th the Church Council discussed the building of a war memorial to

commemorate the young men of Tring who gave their lives during the

war. It was suggested that the memorial should take the form

of a crucifix, similar to the roadside memorials which are found in

France and Belgium. This would be very familiar to all the

soldiers who had served and would be a fitting reminder to the

living and memorial to the dead. It was agreed to commission a

design showing Christ crucified on a cross.

War savings groups were being formed. Street Marshals

collected the pennies in exchange for stamps which were affixed to

cards. When full (15/6d) they were exchanged for a certificate

worth a pound sterling in five years. This type of saving

continues to the present day in a similar form with the National

Savings Bank.

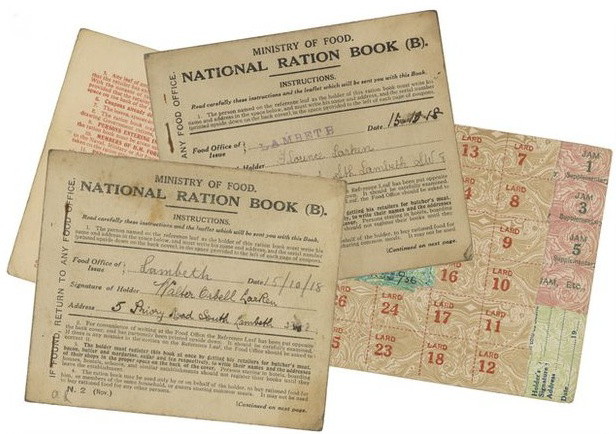

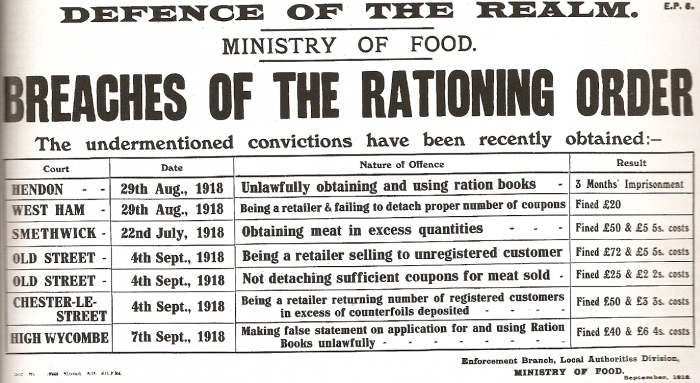

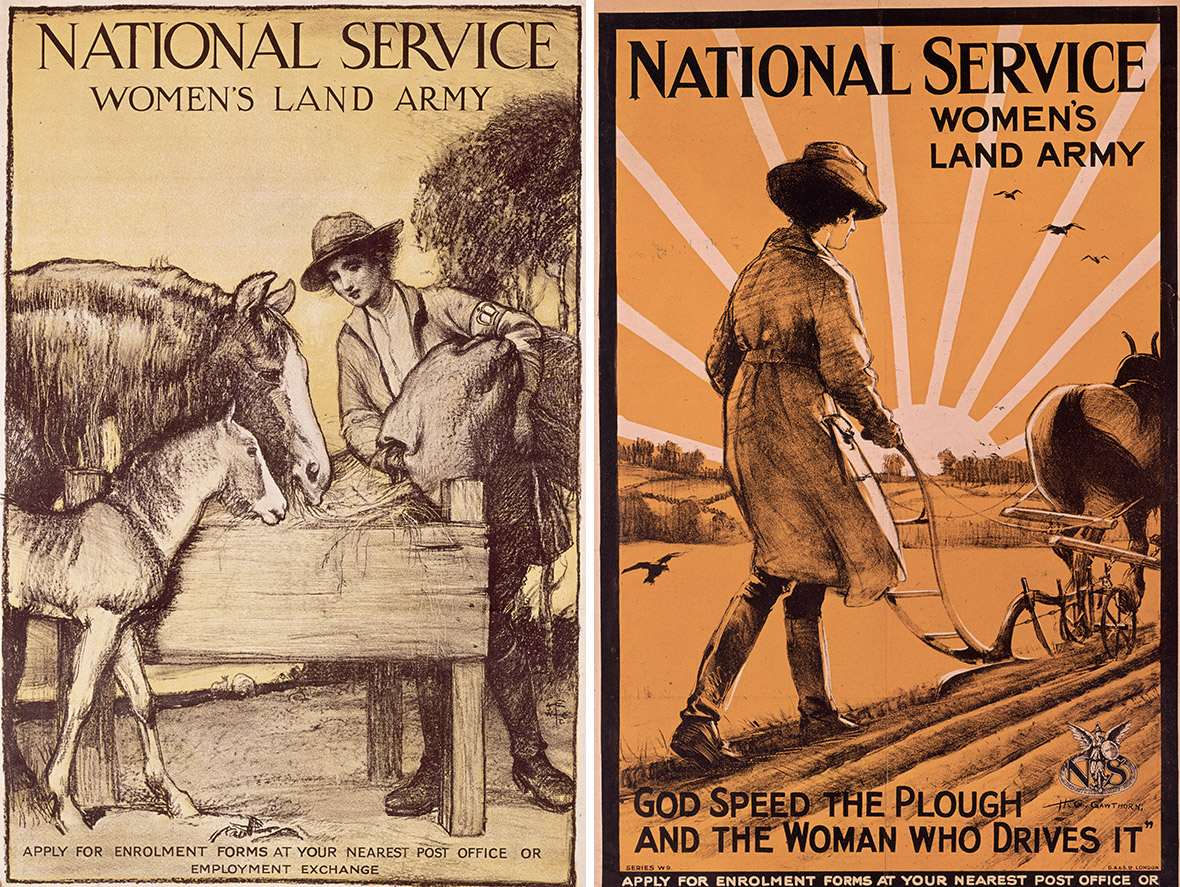

Rationing (1917): food is becoming short due to the German

submarine warfare waged against our merchant ships.

The shortage of

labour on the land is being circumvented by the formation of a corps

of women volunteers known as The Women’s Land Army. Young

women are also being directed into munitions factories. The

naval and military have their own women’s arms, the WRNS and WAC’s.

The women are taking over the duties of motor drivers, cooks,

clerks, etc., allowing the release of men to fill the gaps in the

fighting services.

Halton is still the Eastern Command Training Depot. The Royal

Flying Corps are moving into the North Camp area. A flying

field has been established, with an Australian squadron flying from

it. The Royal Flying Corps training organisation, concentrated

in the new workshops being built by German prisoners of war under

the direction of the Royal Engineers, has trained 15,000 Air

Mechanics during 1917.

A Handley Page 0/400 bomber displaying Royal

Flying Corps insignia at the

Australian Flying Corps Training Depot,

Halton Camp.

On the Western Front, an offensive was started in the Arras area

during the early spring. The German army was pushed back,

resulting in the capture of Vimy Ridge by the Canadian Army Corps.

Although the high ground was not of a great height, it did hold a

commanding view over the Douai plain, with its coal mines and

industrial complex towards Lille and the south Belgian bulge.

The Bolshevik revolution, and subsequent peace with Germany, has

allowed thousands of German and Austrian troops to be moved

westward. The entry of the United States into the war partly

evened up the score, but the Americans were largely untrained in

warfare.

In the autumn of 1917 an offensive move in the Ypres area was

launched, to break out from the salient. The objective being a

possible capture of the Channel ports of Ostend and Zeebrugge, which

were bases for the “U” boats engaged in sea operations in the

Western Approaches.

1918:

On April 1st the Royal Air Force was born by the amalgamation

of the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service. As

aircraft developed, an offensive strategy developed whereby enemy

lines of communication were attacked. Even industrial

complexes were attacked in the Ruhr and Saar areas.

|

A First World War British bomber,

the Airco DH. 4.

During the last five months

of the War, British aircraft dropped a total of 550 tons

of bombs (including 390 tons dropped by night) on German

targets for the loss of 109 aircraft. |

The German nation was beginning to crack. Lack of food and the

casualty lists were causing and demonstrations throughout greater

Germany. Early in 1918 the German High Command launched an

offensive westward in the Somme area, pushing back our forces almost

to Amiens.

|

German troops advancing

during Ludendorff’s Spring offensive, March 1918.

Germany had the temporary

advantage in numbers afforded by nearly 50 divisions

freed from the Russian front following Russia’s

surrender. |

Food shortages and unrest was showing throughout Britain, very

similar to Germany. Socialism was surfacing taking heart from the

success of the Russian Revolution.

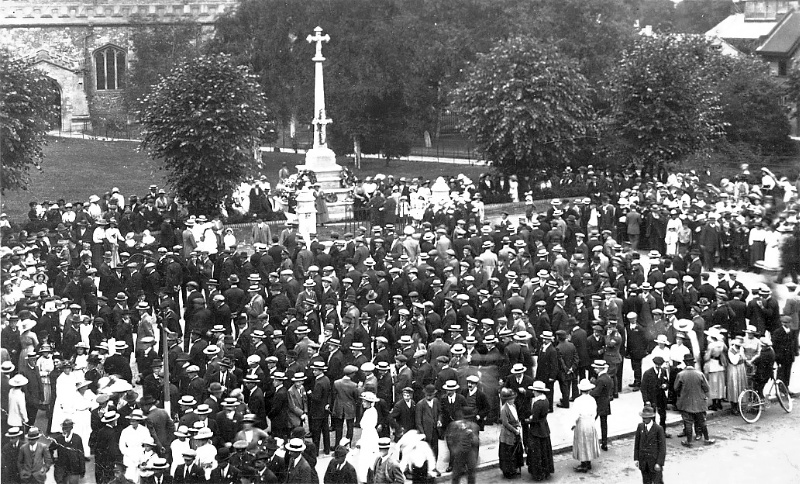

The Tring war memorial is nearing completion. It is hoped that the

unveiling and dedication would be held on St Peter’s day 29th June

1918. Due to various delays the memorial was unveiled and dedicated

on 27th November 1918.

Thanksgiving

for Peace on Church Square: 24th July

1919.

The War Memorial is in the background.

The Parish Magazine for April 1918 published a letter from an

officer in the Royal Flying Corps in Italy:

“The other day I was at

--------- aerodrome, it began to snow, so I beetled back here as

rapidly as might be. The snowstorm put up a pretty good fight

but we beat it alright. But we had to go! Normally I fly

at 50-55 miles per hour, to ease the engine, but I saw now that I

should get a move on. So I started at 70 mph, and for the

first 10 miles kept level with the storm, which was about a mile

away. I could see quite clearly up to the south but then it

looked like a thick white mist. I said to myself ‘My child,

carry on at 80 mph’. But even at this pace the snowstorm

gained on us slightly. In the end we beat it by four fields.

I have been caught too many times by rain and muck to take any

chances by going slowly. These jiggers will do 105 mph near

the ground and I was flying at only 800 feet. It was quite

amusing and my engine was priceless.

I went up for a joy ride the other day to try the electric heating,

which I think I told you about. There is a 250 volt dynamo on

the machine driven by a small propeller 18" across, and a switch box

containing about eight switches. Three of these are for body,

hands and feet. For your body, you put on under your tunic, a

wash-leather waistcoat, which has resistance wires all over it.

For your hands you have thin cotton gloves, with wires down the back

of each finger. For your feet you have socks - the sort you

put in your boots when they are too big - these also have resistance

wires in them.

The other switches are: (1) for heating the guns to keep them from

freezing; (2) to power the klaxon horn used for contact while

flying; (3) for navigation lights, which are on the wing tips and

also behind the observer, and underneath the machine. (these are to

show who and where you are in night flying), (and also to prevent

being run into); (4) for charging accumulators for wireless; and (5)

for Holt landing flares under each wing for night landing, and are

fired by a hot wire.

When I got up I turned on the three body switches and everything

worked gorgeously. In fact, I had to turn the hands switch off

after a bit as they got too hot.”

Letter from a Royal Engineer (Signals) officer April 3rd 1918:

“At last! After

twelve of the most strenuous and exciting days I have ever known,

the remnants of us are safely out for a bit of green field, able to

sleep. Ever since the fight began we have been at it all day

and all night - fighting, marching, retreating, counter-attacking,

etc., etc.

Out of the twelve nights of the fight I was four nights without a

wink of sleep and have certainly not averaged three hours sleep out

of the rest of the twelve days. Never had boots off, except

once to wash my feet; shaved about three times; washed hands and

face about every other day; and with it all have been wonderfully

and marvellously fit - huge appetite and perfect digestion, walked

and ridden countless miles without fatigue or soreness; and come

right through it without a scratch. A most wonderful

experience!

Yesterday we came out of the fight battered and dirty but still

cheerful. I ended up by an all-night march of 24 miles, so

tired and sleepy that I could not remain on my horse, but had to

walk to keep awake, after which I slept all morning, most of the

afternoon, and all night, and could still do with more.

The Signal Company has been pretty fortunate on the whole in the way

of casualties, one officer killed and some valuable NCOs, but very

few men and only three horses.

When we are refitted we will, I suppose enter the fight with renewed

vigour. The end is not yet, and though the Hun has won the

first act, it does not follow that he has won the rubber. Our

post has been held up from the start but I have received it all

together yesterday.”

Bucks Herald, June 1918. Herts Recruiting Campaign for

Women on the Land:

“A recruiting rally for women on the land will be held in Tring on

Saturday, June 8th. A procession of land army girls and part

time workers from Tring and surrounding villages, decorated wagons,

etc, will start from the ‘Britannia’ at 6 p.m. and march through the

town to the market place, where a short open air meeting will be

held.

A letter thought to be from Lieutenant Kesley, published in the

Parish Magazine, June 1918:

Palestine

“I have been moved from camels to donkeys; the Corps is under the

same administration as camels, and is newly formed, so of course it

has to be officered, and I have been selected as one of them and

posted to No 1. It is really a big scream. I wish you

could hear the noise at feeding time. I have 500 of them, and

it is a regular Donnybrook! Of course, I am no longer on the

coastal sector and probably, shall have a chance of getting to

Jerusalem, which is about 25 miles distant, but the country is about

the worst I have ever struck. It is very mountainous with

hardly any cultivation, and the mountains are covered with huge

boulders of rock, and only donkeys can get about on them, with the

exception of goats. But they are not forming a goat corps yet!

We seem to be away from the world up here, away in the hills.

Everything is very quiet except for the hum of an aeroplane; it

seems almost living a hermit’s

life.

Later: At last I have seen Jerusalem. Just before entering the

city, Nebi Sainwil, the traditional tomb of the prophet Samuel, is

clearly visible from the road. This where some of the stiffest

fighting took place, and one cannot understand how our boys overcame

such strong positions; it was superhuman. I took a guide to

the Holy Sepulchre; there I saw our Lord’s tomb. The church,

which is built over it, is very beautiful inside. I cannot say

what passed through my mind as I stood by the side of his tomb, but

everything seemed to be at peace. I also saw the mosque of

Omar, the Jews’

waiting place, and the garden of Gethsemane. It is hard to

realise what happened here.”

June 1918: Letter from Guy Beech, Chaplain to the Forces, former

curate at Tring.

With a Middlesex Regiment Battalion B.E.F., May 3rd 1918.

“As the address shows you, I am now attached to the ‘Diehards’.

My last letter was written just before I left the reinforcement camp

to join the Division. Eventually I reached it close to the

town I had left the week before I was posted to this battalion whose

padre had been killed in the recent fighting. But how long I

shall be with it is uncertain, as it seems likely to be broken up,

which will mean my being transferred to some entirely different

unit. Most of the men have been drafted away, and their place

may possibly be taken by Americans. We have been perpetually

on the move from one village to another in back areas, quite a long

way from the fighting line. We are billeted in first one, and

then another French house; usually a farmhouse built four square

like an Oxford college quad, and usually with a refuse heap in the

centre!

In the last village my bedroom overlooked a pretty little valley

with an aerodrome on the opposite hill and on clear evenings I used

to watch the aeroplanes come out one after the other from their

hangars, like wasps from a nest, and go off in formation, laden with

bombs for the enemy territory. Here in another farmhouse, I am

roused at by the old French peasant starting forth with his plough

and horses for the fields. The French are indeed wedded to the

soil. Everywhere you see them working on the land, the women

and old men, and there they are from sunrise to sunset every day.

Doubtless it is one great reason of the strength of France, and one

can’t help wishing we English people loved the soil as they do.

We are under orders to move again tomorrow and have a seventeen mile

march before us.”

G.B.

An Economic View, published in mid 1918: IT CANNOT LAST.

Through one means or another many people are earning large wages.

Hundreds of firms are paying excess profits tax. And many

workers outside the big industrial world are receiving salaries and

wages, which, for purely war reasons cannot last. Thousands

are earning comparatively good pay, which they will take as a matter

of course until ‘their services are no longer required’. What

is to be the future of these?

There are two distinct types of worker: first, the organised wage

earner; second the new worker in office situations. The first

section, though quite aware that the war (and war prices also) are

liable to fall when peace comes, will look to the State to prevent

the dislocation and unemployment that have followed previous wars.

But a guarantee against actual want does not mean continued

prosperity. Even when a minimum wage is the rule it will be

far less than the present maximum. The second section is in

a position quite undefined. To both the National War Savings

Committee offer sound advice when they say, ‘Save while you can and

buy War Savings Certificates’.

Let us grant that the State would not allow wholesale

disorganisation and unemployment. But let us remember that the

State, like the individual, depends on trade. It is impossible

to guarantee high wages, for the so called ‘good times’ of war

depend on artificial causes. It is to be hoped that new trades

and fresh energy will flourish and abound. But behind such

hopes lies the plain fact that the men and women with £10, £50, or

£100 in hand will be saved an anxiety. For no state exists

that can restore to its citizens what has been lost or wasted, or

create wealth out of thin air.

It is not necessary to buy certificates one by one. £1

certificates are issued in book form; or twelve may be bought at one

time (on one certificate) for £9-6-0 and £25 certificates cost

£19-17-6 each. If you have any odd sum, you can put it all

into certificates in exchange for one document and you can withdraw

part of the money at any time if you need it. A small reserve

fund may make all the difference some day, between having to jump at

the first job that comes your way, and being able to wait until you

can secure congenial occupation. The certificates you buy

today may mark the turning point of your career.

Education: the Rev. Basil J. Reay, Diocesan Inspector of

Schools, paid visits to each of our schools during July and has sent

us most encouraging reports. From these we make the following

extracts, which speak for themselves:

“The school is in excellent hands, and the scholars are being

taught to think for themselves, with very good results. I was

particularly pleased with the way in which the bible narrative was

known, and with the clear evidence of the application of the moral

and practical lessons to the lives of the scholars. The tone

throughout the school was excellent”.

“This was an excellent school in which the scholars are being

very fully taught and where, not only is the knowledge imparted, but

the children are being encouraged to think. The staff are to

be much congratulated on the result of their care and instruction.

An excellent tone was apparent, and the keenness and bright

answering of the children was delightful”.

“The children have received careful and sympathetic teaching for

which they made, on the whole, an adequate return. Good work

has been done, and many of the children answered in an intelligent

manner. The tone and reverence was pleasing”.

“There was evidence in this school of careful teaching, and keen

interest on the part of the children; and in both classes, the

answering was bright and general”.

We are sure that all our readers who have a care for the well being

of the rising generation, will read these remarks with real

pleasure, and will congratulate those who have made it possible for

the inspector to make them.

August School Honours:

Boys: Kenneth H. Desborough has obtained one of two open minor

scholarships at Berkhamsted School. Francis Mildred has won a

County naval scholarship. John Lines, who passed the written

part of the examination, was disqualified due to defective eyesight.

Girls: Nora Lines has been elected to a free place scholarship at

Berkhamsted High School.

Our congratulations to teachers and scholars alike.

September 1918. The War Memorial: the total sum as estimated

for the erection of a war memorial: £450-0-0 has now been received

from public subscription. The cost of the wrought iron gates

is considerably more than first estimated, and it is expected that

more costs will be incurred, so contributions are still needed to

offset unforeseen costs.

Christmas and Tring men at the Front: the vicar called a

representative meeting of the inhabitants of Tring, at which it was

decided to send all of our men in the Royal Navy, Mercantile Marine,

Army and Royal Air Force, and those in hospitals will be sent a

postal order to the value of 5/-. A parcel, or money where it

is safe to send it, to the value of 10/-, will be sent to our

prisoners of war in enemy hands. Collections for this

enterprise, and names of entitled to receive this gift.

November 1918: on 11th November an armistice was signed, to

cease hostilities at 11.00 a.m. on that day. There was great

rejoicing throughout Great Britain.

An excerpt from the war diary of Mrs Ethel M. Bilborough, of

Chiselhurst, Kent: November 11 1918:

“I was trying to write a

coherent letter this morning when all of a sudden the air was rent

by a tremendous bang! My instant thought was a raid! But when

another explosion shook the windows and the hooters at Woolwich

began to scream like things demented, and the guns started

frantically firing all round us like a mighty fugue! I knew

this was no raid, but the signing of the armistice had been

accomplished! Signal upon signal took up the news; the

glorious pulverising news - that the end had come at last, and the

greatest war in history was over.”

General Robertson

presiding at the Tring War Memorial unveiling ceremony

(Robertson remains

the only British soldier to progress from the rank of Private to

that of Field

Marshall).

The unveiling and dedication of the Tring war memorial was performed

on Wednesday November 27th 1918 on the Church Square at 3.30 p.m. by

General Sir William Robertson GCB, KCVO, DSO (General Officer

Commanding in Chief, Great Britain), who gave the address. The

memorial was then dedicated by the Very Reverend T C Fry DD, Dean of

Lincoln. |

The Treaty of Versailles Ends World War I, but

German resentment over harsh peace

terms leads to a rise in nationalist sentiment and the eventual rise

to power of Adolf Hitler.

In this painting is by the Irish artist William Orpen,

President Woodrow Wilson (United States - holding papers),

and Prime Ministers Georges Clemenceau (France)

and David Lloyd George (Great Britain), are seated centre.

|

1919.

The Treaty of Versailles was signed on 18th June 1919 so ending the

Great War. A national day of rejoicing was set for 19th July.

However this date was brought forward to Sunday 6th July.

This, of course, caused some confusion, however all went well on the

day. The festivities started with a short service on the

Church Square at 11 a.m. followed by festivities in the park.

A good time was had by all.

――――♦――――

THE COUNCIL

Written by Bob Grace, Tring Councillor.

In the local paper in December 1894 there appeared a tribute to the

Local Board of Health written by Mr J. T. Clement:

|

“Farewell old Local Board, farewell

Thy end is drawing near

But ere the fatal moment comes

Hear thee a word of cheer” |

The writer goes on to give a factual but light-hearted account of

the work done by this forerunner of the T.U.D.C. [Tring Urban

District Council] In this very short note on 79 years of

Local government, I have tried to follow Mr Clement’s lead, alas not

in verse.

|

|

|

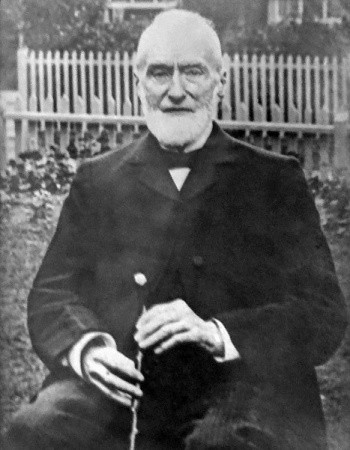

Frederick Butcher

(1827-1919). |

The first [Tring Urban District] Election in December 1894

had been well contested and Mr Stevens, Boot and Shoe Maker, topped

the poll, he being a very respected townsman, always available to

help with your problems, and a Baptist lay preacher of note.

At the first Meeting (3.1.95), Frederick Butcher, local

Banker of Frogmore, member of H.C.C.

[Hertfordshire County Council] was made Chairman. The

Hon Walter Rothschild (later 2nd Lord), M.P., was also a member.

Glancing through reports, no doubt these great bankers gave their

careful consideration to the Granting of a Pawnbroker’s Licence to

Mr Seabrook and that Mr Attwell of the Red Lion could hold a Lodging

House Licences for his 1/- a night boarders; the first Rate of 2/6

in the £ brought trade to Mr Seabrook.

Under Mr Butcher’s Chairmanship and the guidance of Mr A. W. Vaisey

as Clerk (salary £125.0.0d per annum) the monthly meetings were

referred to as a “Duet with Occasional Chorus”. Health was and

still should be the prime duty of Local Government. At this

period Scarlet Fever and Diptheria epidemics were rife and the

building of the Little Tring

Hospital was an enormous boon to the Town. In 1902

Smallpox was endemic and patients were housed in a tent at Aldbury –

to quote Mr Clement:

|

“But human faces marred and scarred,

Eyes darkened, long have been

Things of the past, for rare now

Such saddening sights are seen.” |

This plague was still with us. By May 1903 the Matron of the

new Hospital felt that after eighteen months’ work she might ask for

three weeks holiday, which was promptly refused, but she might take

14 days on the understanding that she returned if a patient was

admitted.

The Station Road, which had had ruts three feet deep, had now been

surfaced with flint, with the aid of a steam roller. The

Landlord of the Robin Hood was sent a bill and strong letter for

having managed by diplomatic means to get the roller to rolls his

yard without the surveyor’s knowledge! The Council felt that

the Station bus should now be able to meet the trains and as it was

failing to do so, consideration to a take-over almost succeeded.

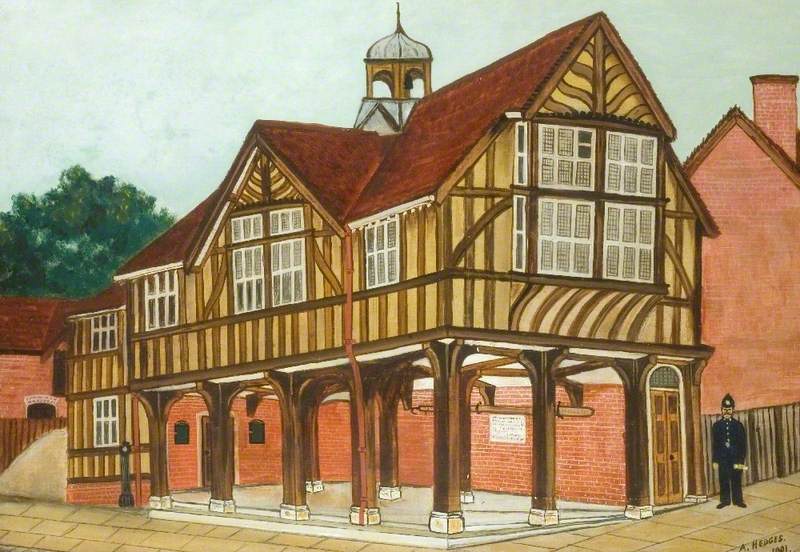

The New Market House, High Street,

Tring,

by A. Hedges (1901).

|

|

|

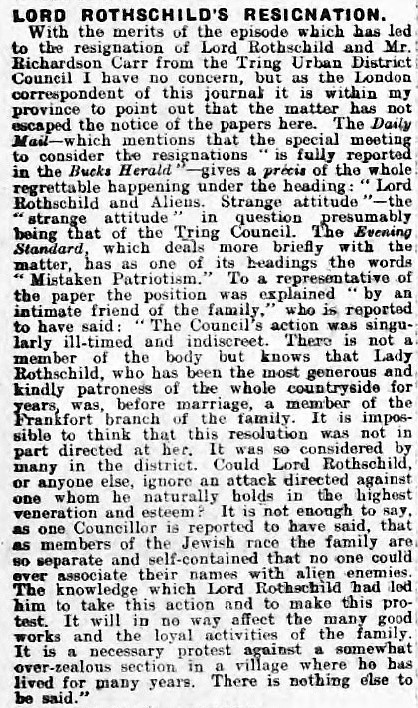

Bucks Herald, 24th

June 1916 |

Meetings were held in the market house in the room which had been

designed as the Market Hall and Corn Exchange. Members

complained of cold feet and in 1910 the ground floor was enclosed

at a cost of £90.0.0d. Heat was, however, generated when the

Surveyor, who had to cover the 25 miles of district roads, asked for

£5 per year bicycle allowance, which was allowed by a small

majority, but the request for a telephone at £5 per year with all

local calls free was immediately refused. Refuse collection

was late and uncertain and was only able to continue when Cllr.

Rothschild used his good offices to get permission for the ash carts to tip

[refuse] into the

disused canal at Little Tring. Traffic through the Town

now came in for attention and 1911 saw a request for a Motor Speed

Limit. This was eventually granted from Langdon Street to the

Rose and Crown. At this time it was possible to buy milk at 11

dairies and milk shops; bread from 12 bake houses; meet from 7

slaughterhouses, and to work in 26 factory premises. 616

children were at school. Death rate 15.3 per 1000 – Birth rate

18 per 1,000 – BUT death of infants under 1 year, 61 to 1,000

births! If since 1912 the Council has helped to bring this

figure to Nil in 1972-73, it has justified its existence.

The 1914-18 War did not miss Tring. Rate relief was allowed

for houses

given over to Belgian refugees and its hospital, schools and hall

became Tring Military Hospital, which in 1915 was receiving patients

from the Dardanelles. The writer would have voted in support

of a request from the School Managers for “Better heating at Church

House and Market House, now used for the school”, for during the last

winter the temperature did not exceed 40ºF on many days (I remember

trying to sit as near under a gas light as possible with my overcoat

on). Council, however, became very heated and passed a

resolution that “All aliens be imprisoned or deported” – this

was in bad taste to say the least, considering the position of the Rothschilds and their employees, many of whom came under this

heading and in many cases were fighting in the Allied Forces.

Lord Rothschild and the chairman of 16 years standing, Mr Richardson

Carr, resigned immediately! On the reverse face, however, a

move to mark the award of the V.C. to Edward Barber was voted “No

Action”.

|

|

|

The Rev. Charles

Pearce. |

The next Chairman, Pastor Charles Pearce, spent weeks

visiting as many wounded Tring men in hospital as possible and the

Council agreed to tend the graves of the fourteen soldiers who died

locally and are buried in our Cemetery.

The price and scarcity of meat caused public concern and the Council

set up a Food Control Committee. They tried without success

to stop animals sold in Tring Cattle Market leaving the town; they

also failed to stop Council workmen leaving to work at Halton Camp

for 10d. per hour! The Armistice was greeted with the public

demand via Sir Steven Collins, M.P. for a ‘War Trophy’. This arrived

in the shape of a very old German Gun, which appeared never to have

been able to fire. From its place of honour in the Market

Place it was moved to Miswell Lane Recreation Ground from where it

was quietly sold for scrap metal! The further gift of an

ex-service ambulance was refused owing to the cost of a garage and

insurance.

|

|

|

Private Edward Barber

(1893-1915) V.C. |

1918 brought the great Influenza Epidemic and Health properly took

precedence over business. The surveyor was instructed to get the

ventilation improved in the Empire Picture Palace, Akeman Street.

Prices came under examination and seven members formed a

Profiteering Committee. There is no report of anything being

done at a stroke, but as is usual a Coal Strike followed and all

the gas street lights were

extinguished. Two

lamp-lighters were part-time employees and it was decided not to pay

them even half wages for the strike period.

A report that boys were playing football in Miswell Lane Recreation

Ground on Sundays was passed to the Police to stop it. They

refused to take any action. It was then forwarded to the

Ministry, who in those days could give a definite answer in return,

which again was No! Further complaints from Miswell Lane

concerned an industrial site, where sausage skins were processed –

this time the complaint was smell rather than noise!

By the mid-twenties leisure appeared on the agenda and the need for a

swimming pool was noted. Next the Education Committee added

their pleas for it and within ten years a Swimming Pool Committee

was set up. The first application to set up the County Library

in Tring was turned down “As against the interests of shopkeepers”.

However this was reversed at the next meeting and, to rub the result

in, the books arrived on a Sunday! The library had to be run

entirely voluntarily and a payment of £2 paid by the Council

was overruled by the Ministry and had to be found by public

subscriptions. By 1928, 648 people were on the list and 473

books were permanent. In 1932 it was allowed to pay a

Librarian £13 per year on the condition that it opened two

nights per week, the approximate lendings being 250 per week.

In 1936 the books were turned out of Market House to the Junior

School in the High Street. In January, 1937, Mr. Thomas Grace was

appointed the Chairman of the Library Committee, a post he held

until its last meeting, with at least one other member who has been

on the Committee becoming the Council’s longest serving Committee

Chairman.

|

Photo courtesy of

Mike Bass.

Besides being a

long-serving town councillor and a well known local historian,

Bob Grace (author of this account) was famous in the locality for

his lantern slide shows. |

In 1928 the Health of the town was again to the fore. The

Surveyor reported over 70 cases of overcrowding and, to the M.O.H [Ministry

of Health], that 34 houses were unfit, some of which had been

condemned in 1914 (one or two remain today). Many children

from these homes who attended the Council School were suffering

from T.B. [tuberculosis] and Ricketts. He reported that

the tenants of these houses could not afford more that 3/- to 5/- a

week rent inclusive. The Council, who were refused Ministry

help, could not rehouse these people and a voluntary scheme was set up at New Road, the houses being

built by a public appeal headed by Chairman John Bly. One man

without a home found to be living on his council allotment was

ejected as a trespasser. With all his extra Health work the

Surveyor asked to have a typewriter, which was firmly refused,

as was the public’s request to be able to pay for the newly laid-on

electricity in the Town. It was, however easy to reach

Aylesbury to pay; Premier buses ran every half hour, Viking express

coaches at the hours, Chiltern buses if required.

The Council received complaints that people were shopping out of

Tring and tried to get the licences of the buses reduced, but by

1934 the L.P.T.B. [London Passenger Transport Board] cut all

services to one per hour and did not connect with the trains.

Only after many meetings was some improvement made. It was, however,

possible still to use the Canal. 76 boats were Tring

registered, eleven being motor. Road traffic was causing

concern and in October 1932 the County Surveyor was asked to improve

Cow Lane to the London Road junction, and two months later to consider

traffic lights at the Akeman Street/Frogmore Street corner. By

1935 the Council was refusing a pedestrian crossing in High Street,

and the Road Safety Committee placed their resignation en block

in the hand of the Council to try to get the crossing, which did not

come until some thirty years later! Town Planning was not a

council power in 1933 but it was agreed to do all they could to

oppose the setting up of a Motor Race Track at Folly Farm on land

which, when this was refused, was bought to set up the Cement Works.

It was refused to signpost field paths but it did, however, under

pressure from the Surveyor, draw up a map of all the known rights of

way!

In 1937 a joint Planning Committee with Berkhamsted U.D.C. and R.D.C

drew up a Town Plan and recommended an industrial area between the

Station and New Ground. Green belt areas were agreed and the

purchase of the Woodlands pressed forward by Chairman Donald Brown

M.C. He had the difficult task to prepare for War. An

A.R.P. Committee was formed, and First Aid etc., was instructed by

Cllr. Kettle, at first with little support, but the report to the

Council, October 1938, that Air Raid Trenches had been dug at

Miswell Lane, Dundale Road, near the Brittania, High Street and the

School, brought the threat home and work really started.

With the arrival of evacuees requiring another Committee, which was

most unpopular, and in September 1940 the first bomb brought War to

Tring!

When Victory came, the Clerk reported 1,152 Red Warnings, 15

incidents, 36 High Explosives, 2 Land Mines, 1 Oil Bomb and a number

of incendiaries, 162 houses damaged, no-one killed or injured,

although the incidents included air crashes in which Service

personnel died. V.E. day had been celebrated by street parties

but proposals to welcome home members of the Forces failed to get

enough support, except to send most a pocket wallet.

However, a new Committee of Townspeople was forming, that of the

Ratepayers Association (now Residents) and at the next Council

Election they won all the seats. From this date, a study of

the Minutes of your Association gives a picture of Council

proceedings in which the writer has pledged some part and I will not

comment further.

To again mis-quote Mr Clement:

“So cheer up then thou U.D.C.

As now they labours cease

May you now rest in peace!

Tring then in future years may be

A place of just renown

By ‘Dacorum’ wisely ruled,

An Almost Model Town!” |

R. G. Grace.

――――♦――――

TRING FIRE SERVICE

This piece (author unknown) appears to have been written in the

1970s. |

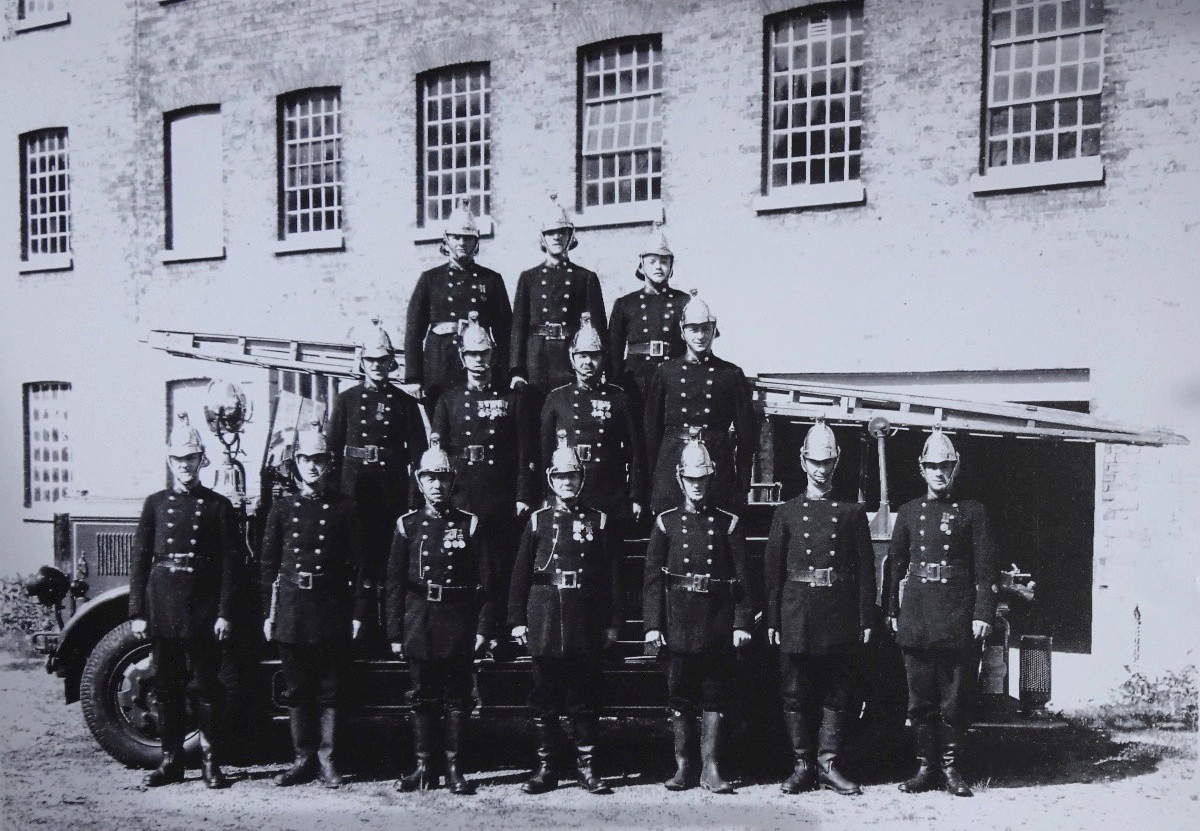

|

Tring Fire Brigade posing

with their horse-drawn fire engine, which remained

in use for almost

two hundred years before being replaced in the 1920s.

Spare a thought for the apparently impatient driver behind you next

time you are in a queue of cars in Tring High Street. Don’t

discount him as another menace soon to be removed by the opening of

the by-pass [opened 1973]. He could be one of Tring’s

vital citizens and one day you may be thankful that no queue of

traffic impedes his journey.

Why? Well he could be driving Tring’s fire engine. Tring

Fire Station is manned by thirteen able-bodied part-time officers,

three of whom live and work in Tring and are thus on permanent

standby. A fire alarm these days is not sounded by the old

-fashioned siren. Electronic wizardry provides each fireman

with a personal alerter which operates within a five mile radius.

These have been available for three years and although more

expensive are much appreciated by the neighbours of the siren tower.

A radio signal from Divisional Headquarters triggers a device at

Tring Fire Station. This transmits another radio beam which

when received by the alerters causes them to emit a buzzing alarm.

It is then down tools and off to the fire station with grateful

thanks for an understanding employer.

The Brigade with Tring’s first

motor fire engine. It was so under-powered

it could not climb the hill to Wigginton.

The staff of the station – in official jargon it is a Retained

Station – come from various walks of live. The occupations

they hold include a painter and decorator, printer, farm worker,

factory foreman, electricity board worker and security officer.

They are led by a Sub-Officer Gosling, and to help him in his work

he has two leading firemen and ten firemen. This band of volunteers

cover a wide area round Tring, including Wigginton, Pitstone, Hastoe,

Cholesbury and Aldbury. During the day only three men work within

range of the alerters, but at night all thirteen can be raised by

this system. It is the first seven at the station who go out on

call, six to man the fire engine and one to remain on watch at the

station; not surprisingly this latter job is the less-favoured of

the jobs. These men enjoy the thrill of not knowing what they might

be going to deal with when an alarm comes. The type of call can

range from a simple chimney fire, involving no mess with modern

equipment; to pulling a donkey out of the canal. The firemen can

cope with all types of calamities including flooding, grass fires,

motor accidents and even light aircraft crashes. The fire engine, or

pump, is modern, with a 400 gallon tank of water and a 35 foot

extension ladder. It also carries breathing apparatus, equipment to

deal with chemical spillages from lorries winches and of course a

two-way radio.

Tring Fire Station had at least one hundred calls a year, with

happily few false alarms. The men are proud of their record of a

four minute turnout to any call, and that includes travelling from

home to the station. If you have volunteered to be woken at anytime

of night after a hard day’s work, with the knowledge that you have

to be in the next day at work after a call, you would expect some

financial recompense. Payment these men get, but hardly worthy of

the task they perform is £1.95 per turnout for the first hour, which

after tax deductions, and if a daytime call-out also loss of working

hours which have to be made up, leaves a fireman with little

compensation for his trouble. But it is just such dedicated men who

provide you with the security of help when you dial the triple nine. |

|

Tring Fire Brigade with their

new Leyland fire engine outside the Silk Mill (c.1930s).

――――♦――――

ALL BECAUSE THE FIRE BRIGADE WASN’T THERE?

by Denis Aldrige, May 2000

There had been a fire at Spencers Green in January 1926. The

Tring Fire Brigade had not attended. Members of Tring (Urban

District) Council wanted to know why the alarm bells had not been

rung; who should have rung them; and why had no effort been made to

go to the fire. In other districts the police rang bells to

alert members of the fire brigade. In Tring the police had to

notify Mr Gilbert Grace who maintained the alarm bells in his house.

On this occasion the police had notified Mr Grace who had then

consulted Mr Putnam, Captain of the Brigade, who was nearby.

The Captain decided not to attend the fire because he believed that

the brigade’s hose would not reach the nearest water supply (at Ebbs

Pitt Pond below Dancers End) and he was sure that the Aylesbury

brigade had a longer hose and could get there more quickly with its

motor engine.

Tring police had notified Aylesbury and the Aylesbury appliance had

indeed got to the fire quickly and had dealt with it satisfactorily.

Nevertheless councillors regretted that Tring Brigade could then, at

least, have offered to help the Aylesbury men. In fact, there

was no certainty that horses or firemen were available in the town

during the working day. Cllr Goddard contended that seven

firemen had been available. But that was not known at the

time. Moreover councillors were aware that when a serious fire

broke out in Mr Howlett’s bakery on an afternoon some months before

only one fireman was to be found and the building had been badly

damaged.

The immediate result of the Spencers Green fire was that Tring

Council unanimously decided that its fire engine and hose cart

should be fitted with drawbars to enable them both to be attached to

a lorry. Two firemen were to travel on the fire engine to

control it and the remainder were to go on the lorry — Messrs Gower,

Prentice and Rolfe agreed to allow their lorries to be used for this

purpose. — The Surveyor was also asked to look out for a more

up-to-date, second hand engine and for motor pumps on sale.

The captain of the Brigade took umbrage at the implied criticisms of

his actions and gave notice of his resignation with effect from 31st

March. This distressed the Fire Brigade Committee which

promptly passed a resolution expressing its confidence in Mr Putnam

and asking him to reconsider his decision. The Captain was

only prepared to do so if the Council would agree to provide the

Brigade with adequate equipment. The Committee immediately

asked him to draft a list of requirements in order of priority (lest

the Council would not agree to buy everything at once).

A rick fire at Church Farm, Marsworth on the evening of August 7th

concentrated councillors’ minds still further. After the fire

alarm had been sounded in Tring “a large crowd assembled outside

the fire station and cheered ironically when the Brigade eventually

got away alter a long delay -- due partly to the fact that the

arrangements for hauling the fire engine with a lorry and drawbar

attachment did not work very smoothly ...... the new method was

tried because of the difficulty in getting the engine horsed.”

On arriving at the fire there were further problems. The

engine had not been used for some time so the leathers were dry, and

for a while only “a tantalising trickle of water could be pumped.”

Nonetheless the Brigade was able to save much of the 21 ton hayrick

and prevented the fire spreading to farm building and to two other

ricks.

The Council had already invited surrounding parishes to join a

contributory scheme for the provision and maintenance of a new

engine. By 24th January 1927 it was plain that the surrounding

districts had no wish to contribute. Tring Council hoped to

provide £600 from the next budget but that would not meet the cost

of a motor fire engine and the other appliances in the Captain’s

report of March 1926. The Fire Brigade Committee considered

the town to be well equipped with hydrants so it decided that a

motor fire engine would be an unnecessary expense and suggested that

the Council should buy a lorry instead. However, early in

March 1927 the Council accepted an invitation to inspect a motor

fire engine at Woodbridge in Essex on the understanding that they

were not committing themselves to buying one. At the end of

April, still not convinced by the demonstration, the Fire Brigade

Committee wanted a demonstration at the various hydrants in Tring

both with and without the engine. The Council Chairman was

certain that Tring did not need a motor engine and that it was

premature to allocate £600 before they knew what support surrounding

villages would give. At this point, the Council turned its

attention to a letter from Mr Grace inviting it to buy “the

electric alarm bell, switches, batteries, wires, installations etc.”

installed by his father. These items had cost about £50 but he

would be happy to sell them for £25. At that point it was

decided to buy a “half horsepower one mile radius siren” and

eleven 50 foot lengths of hose to the annoyance of Mr Bly who

considered the siren to be a great waste of money. It would

cause a commotion in the town and would not be necessary if they

possessed the bells as well.

Cllrs Goddard and Hedges had grown impatient with the delay.

By mid June I927 the Council still had not been able to secure a

demonstration in the town; only Portslade Council had responded to a

questionnaire on the efficiency of the (Baico-Tonna) engine being

considered; and surrounding villages had not indicated any

willingness to contribute towards the cost. However, Cllrs

Goddard, Mead and Rodwell persuaded the Council to place an

immediate order for this type of machine from Pemsel and Wilson of

Boxmoor. Anxious to reduce the burden on Tring ratepayers,

councillors also agreed to ask for a donation from “certain fire

insurance companies”, from Wigginton, Aldbury and Puttenham, and

for a loan from “the Ministry” to meet a total cost of £600

-- £451 for the fire engine, the remainder for appliances.

The Public Works Loans Board turned them down as “the purpose for

which the loan was required did not come within the class of loans

for which the Board had power to make advances”. It was

the Ministry of Health which approved the raising of a loan of £550

for the Council’s purpose. The villages still showed little

sign of contributing but the lack of their support was only going to

increase the Tring rate by ½d

so in the second week of September 1927 the Council agreed to

continue with the current procedure of simply charging a fee to

cover the cost of call-out to a village fire. Councillors also

agreed to increase Brigade personnel by two or three.

12th October 1927 -

official reception of the new Baico-Tonner motor fire engine.

Messrs Pemsel and Wilson brought the new machine to Tring for

testing on October 12th. It certainly pumped satisfactorily

but it could not get up Marlin Hill and needed several attempts to

reach the top of Hastoe Hill. Dispute then arose between the

Council and Messrs Pemsel and Wilson as to the merits of a low speed

axle and a gear box to remedy the problem. The axle would have

reduced the appliance’s speed to 16 - 18 m.p.h. from its existing 35

- 40 m.p.h. Agreement was finally reached on November 7th.

The firm gave a guarantee that with the gear box fitted — without

further delay and at a cost of a further £17-10s-0d -- the fire

engine would get up any of the hills in the district fully loaded.

The offer was accepted and on December 10th 1927, just a month short

of two years since Tring Fire Brigade’s failure to go to Spencers

Green, the Council received confirmation from the Fire Brigade

Committee that the motor fire engine had indeed carried the men and

full equipment up Hastoe Hill, Marlin Hill and Oddy Hill several

times. Councillors immediately agreed that a cheque for

£476-2s-5d should be despatched to Messrs Pemsel and Wilson.

Whereupon Cllr Bagnall referred to unfair reports which had been

circulated and asked the Press to take particular note that on

November 26th “under conditions none too good as regards weather

and roads, and from a cold start in the fire station” the fire

engine went up Marlin Hill to the Hastoe cross-roads in nine minutes

with full equipment and seven men, and then went from New Ground

Waterworks up Hemp Lane to Wigginton Church in six and a half

minutes.

――――♦――――

THE FIRE BRIGADE

by Jill Fowler, July 2013.

Until well into the 20th century Tring firemen would attend a fire

with a cart pulled by horses. This was said to have been

bought by the vicar and church wardens in 1750. In the 1890s

and early 1900s the horses were usually provided by Mr Gower who had

a removal business. There would be frequent reports of fires

in Tring, many of them chimney fires. One more disastrous fire

was in the hard winter of 1895 when Lord Rothschild’s Home Farm in

Park Road was completely destroyed. Due to frozen conditions

water was not readily available. The captain was Mr Gilbert

Grace from the High Street hardware shop and he led the fire brigade

until shortly before his death in 1914.

Mr Gower eventually changed to a pantechnicon for his removals and

sometimes the horse cart would be pulled by a lorry. The

Bucks Herald of September 11th 1926 reported, under the title of

“Motor Fire Engine”, “Surrounding villages are to be asked

to contribute to a new engine, the other one, now pulled by a lorry,

being completely out of date.” The new fire engine was

soon to prove its worth. The Tring Gazette of 1928

reported: “The provision of a motorised fire engine at Tring

proved to have been fully justified when the brigade fought a blaze

at The Grove. The speed of its arrival enabled most the furniture to

be saved, whereas the whole house would have been burned by the time

the old horse-drawn engine had arrived.”

For years the Fire Brigade was housed in the Vestry Hall near the

church. An early photograph shows the firemen standing in

front of the door with “Fire Engine” in large letters above

them. When the new Market House, on the corner of the High

Street and Akeman Street, was completed in 1899 it replaced the old

Market House that stood in front of the church. The ground

floor was open to supply easy access to the stalls.

Ten years later it was decided that the Vestry Hall was too small

for the fire brigade and plans were made to convert the Market House

for it. The work was completed in the autumn of 1910.

Many older Tring people remember the sound of the air raid siren

wailing from the top of the building and the firemen running down to

man the engine.

There were two major fires in Akeman Street. In 1965 a fire,

said to be caused by a grain dryer, destroyed a large grain store

and drying machinery at Bob Grace’s mill. Luckily the firemen

prevented the fire from spreading to the historic mill, now known as

Graces Maltings.

Ten years later there was a serious fire at Rodwell’s bottling

factory. Firemen fought all night to control it, with six fire

engines in all, from Tring, Berkhamsted, Hemel Hempstead and

Aylesbury. They were most concerned that the fire might spread

to the nearby Natural History Museum. The cause of the fire

was unknown, but most damage was done in the storage department

which housed a great deal of sugar. The bottling department

was able to carry on as usual.

A sad fire was in 1994 when Grace’s 240 year old Parsonage Place

barn, thought to be the oldest in Tring, was severely damaged.

It was said to be arson and a 17 year old boy appeared at Hemel

Hempstead Magistrates Court charged with starting the fire.

Eventually, as fire engines became larger, it was necessary to have

a purpose built Fire Station in Brook Street. The ground floor

of the Market House has now been “re-opened” and houses a shop.

In the early days a lot of the firemen , all volunteers, were

business-men, able to leave their premises at a moment’s notice when

the alarm was raised. They would have been amazed at the fire

engines and equipment available today, but their devotion to their

job, in spite of their difficulties, earned them the respect and

gratitude of Tring people.

――――♦――――

WRITINGS OF FRANK JOHN BLY, ANTIQUES DEALER

The first fourteen years of F.J.B

From the local broadsheet or weekly newspapers a notice - “On the

First of December in the Year of Our Lord 1904, Letitia Bly of 22

High Street, Tring was safely delivered of a male child.” No doubt

this was further repeated at the Baptist Chapel on the following

Sunday where Letitia and John were members, if not from the

Pulpit then certainly from mouth to mouth that “Lettie Bly had a

boy”.

After a short interval a visit was paid to the Registrar of Births,

Marriages and Deaths, and there recorded that one Frank John Bly, son

of John and Letitia Bly, was born on 1.12.1904.

I really remember nothing of the first five years of my life - not

in any real detail - but this I do remember, in 1909 a running

battle started between my dear parents and myself that was to last

for nine long years - I was taken to school.

My first kindergarten was with a lot of other boys and girls whom I

rather liked - or wanted to like - under the tuition of two rather

dear - and to me very old - ladies, the Misses Francis and Daisy

Collins at Elm House, Tring.

According to the

financial means of the parents, education in Tring in my young days meant

that boys went either to the National

School (Church of England plus County Council Aid), the Tring

Commercial School (a private establishment run by Mr Walter Edward

Wright) at White House Tring, or to Berkhamsted Grammar School. My

father chose the middle course, so off I went to Tring Commercial

School. It soon became quite apparent to everyone that I should

never win a scholarship to the Grammar School, so I remained under the

care of Mr Wright until reaching the age of fourteen. I have no

complaint about Mr Wright. He tried, and so did I, but we were

parallel lines; our ideas just didn’t meet. There were so many

things I wanted to do in my father’s workshop, the horse to be

groomed, the motor to be cleaned, anything rather than books.

But

less than a month after leaving school I knew I had been wrong.

Study I must, and study I did, and it’s taken possibly all my life to

make up for lost time. But my boyhood days were wonderful. In my

father’s workshop - a building about 200 yards from the shop -

were Mr Good, upholsterer and polisher; Mr West, cabinet maker; Williams Bradding, a young man doing all the odd jobs; and Lew

Crockett, the groom and general do-it-all.

Mr Good always said I was a “tiresome, interfering and meddlesome

child” (his favourite expression was “don’t meddle boy”). As an

upholsterer he always took a handful of tacks and while working held

them in his mouth. I found a few drops of paraffin dropped in his

tack tin cause him some slight discomfort, which helped me put up

with his meddlesome ways. But I learned a lot from Mr Good.

He was

a man of great patience and long before I left school he had

taught me to straw web a chair seat and hand stitch a hair stuffed

‘roll edge’ on a Georgian stuff-over chair – but I never did put the

tacks in my mouth, just in case!

Mr West always had all the tools I loved to use and from him I

learned at a very young age how to use them – I’ve still got scars

on my hands where the chisels slipped to prove it! But again,

before I left school, I had learned to know one piece of mahogany

from another; French walnut from English; how to iron down veneer

and cut bandings; and cut and shade in hot sand oval shell inlay.

Maybe I was wrong, but to me time spent learning in the workshop

was better than sitting at a school desk.

|

|

|

Frank Bly |

William Bradding, being younger, joined in everything. Our workshop

was heated by an old iron circular ‘Tortoise’ stove, its pipe going

through the wall into the fireplace and chimney of the next showroom.

One late winter evening, Mr Good and Mr West having gone home,

the stove fire had gone out. To restart it we poured some paraffin

on to the hot coke. This didn’t flame but must have turned into gas

because when we put a match to it, it went with a terrific roar.

The stove didn’t move, but a large wardrobe in the next showroom

did, and the hole in the ceiling where the chimney stack

came through the roof left no-one within a quarter of a mile in

doubt that something had happened. Father soon arrived and it was

our first ‘black and white’ show – I was black with soot and father

was white with worry and rage, although he was relieved to find us both alive.

All was forgiven, except for suitable punishment.

I’ll come to Mr Crockett later, but the only one in

the workshop, or anywhere else for that matter, was my father. He

could do everything. To me he was ‘all things to all men’ apart

from being a master craftsman in the workshop, a keen student of

many subjects, a fine judge of English Furniture, an outstanding

dealer, a great teacher and, above all, a wonderful father. He

could make the best rabbit hutches, pigeon cotes, railway stations,

build the best boats and chests for birds eggs.

To my father and mother I was always known as “the boy”. I can

never remember hearing my father swear, but whenever - and it must

have been on hundreds of occasions when I did wrong, or annoyed him

- he said “drat the boy”, into the word “drat” he could get

more feeling, more expression and wrath than any other word I have

ever heard. If it was in the morning, then one “drat” would

cower me for the day. But father practiced what he preached; “let

not the sun go down upon your wrath”, and we always made sure of

saying “good-night”, so that when I woke and my pigeons were at the

bedroom window it was another day to explore, another day to do

things in and (apart from school!) another day to be enjoyed to the full.

My father was one of the founders and secretary of the Tring Y.M.C.A.

He raised money with a lot of help from tradesmen and local gentry,

and equipped a fine gymnasium in what was at one time a chapel known as the Tabernacle. Gymnastic displays were given to raise

funds for needy causes and there are some photos that show the last display

in the Cricket Field just before the Great War. As well as the

men’s

and boys’ teams there was a ladies’ team organised by Miss Gwen Knight,

and one photo shows a display with my sister Doris on the left-hand

side. |

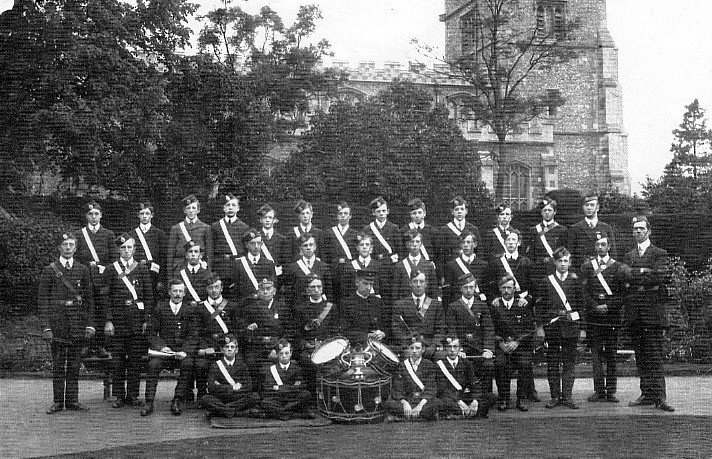

Tring Y.M.C.A. gymnastics

display team (date unknown).

|

Up to about the year 1913 my father had a beautiful grey mare,

‘Dolly Grey’,

who used to pull the four-wheel open furniture van. She was Lew Crockett’s pride and joy.

Her coat was groomed until it

shone, her harness was a picture, and when she went to be shod Lew

would put a blanket and halter on her, put me on her back, and off I

went at 7 in the morning to Mr. Stratford the blacksmith.

Dolly

Grey knew her way.

Mr. Stratford always made tea in a big enamel jug. He threw the tea into

the water, put it on the forge fire, blew the bellows until the

sparks flew and mash the tea. He then poured the milk and sugar into the jug and

out came tea the like of which I haven’t tasted since 1913, mainly, I

think, because the jug was only washed out when it wouldn’t hold any

more tea leaves!

My father bought Dolly Grey from Squire Jenny of Drayton Manor.

She never looked happy when she was in the van delivering or

collecting furniture being driven by Lew Crockett with William Brackley. I am

quite sure she felt it beneath her dignity. We also had a high,

two wheel cart that father drove when out making his calls, viewing auction sales or

attending Aylesbury market every Saturday when we

always ‘shut out’ and stabled at the Chandos Arms livery stables and

public house. As soon as Dolly was harnessed into the cart she

looked completely different. To see her trot was a picture, head in

the air, a proud and beautiful creature. One day when father and

I were going to Berkhamsted down the long hill known locally as Pendley Beeches,

when Dolly stumbled and went down in a heap on the

road. Father and I were both thrown out of the cart. I was of

course crying my eyes out with fright, but father quickly picked me

up and sat me on Dolly’s head which, as any horseman knows, is the

only way to make a fallen horse lay quiet. He then undid the

harness, dragged the cart back so she was clear of the shafts,

pulled me off her head and up stood Dolly Grey, trembling as only

a hurt and

frightened horse can. Her poor knees were cut and bleeding and I can

still see my father tearing up his shirt to bandage those cuts.

We all walked back to Tring. Neither of us ever got over that

incident and

father never drove Dolly again. She had to be taken to

Mr Seaton’s livery stables at Aylesbury where I am sure father sent

her because he wouldn’t have her put down in our own yard. Lew

Crockett had to take her. I saw her go but my father didn’t,

for he loved that grey mare. The cart and van

were sold except for the two solid wooden boards that ran along the

side of the van, which were written in gold letters ‘John Bly,

Antique Dealer, High Street, Tring’. These were taken off and

afterwards used on every van for many years, but eventually our Austin

van was stolen in Watford. The first thing the thieves did was to

rip off the name boards and smash them – we got the van back but not

the boards. I would rather have had the boards, the van I could

have replaced.

During the three years 1913 to 1916, so much happened. The

saddest of these years for father, mother and myself was 1916. I had no

brothers and only one sister, Doris Rose Bly. Doris was nine years

older than I, which meant that for twelve years when I was in any

real trouble Doris was there, guide, comforter, friend and wonderful

sister. Then Doris died from an illness that modern medicine will

cure, but in 1916 pneumonia was so often fatal. Even after

fifty-four years there is still no need for me to look at the old

photography album to remember her. She was such a pretty girl, slim

built, a talented musician on piano and organ. She played the organs at

two local Nonconformist Chapels, both having manually operated

bellows. When she practiced I used to go along to blow the organ

–

often, I regret to say, under pressure. Then within a few

weeks of her twenty-first birthday the end came, and although my

mother lived to be nearly ninety she never really recovered from

losing her Doris.

Doris was engaged to be married to a Tring boy, Archibald Bishop,

who, like most of the boys of that age group was in the Army.

He had been severely wounded in France and brought back to

a hospital near Manchester where Doris had been to visit him a few

months before her death.

Tring was still very much a Rothschild town (of which more

later), but when anyone was seriously ill straw was always laid for

about a hundred yards all over the main road to deaden the traffic

noise, for all the horse-drawn heavy carts and vans had iron tyres and

‘strawing’ was quite a custom to the time. The Great War was

on, so the heavy army gun-carriages and transports made such a noise

that Lady Rothschild had some of the older men who were still left on the

“Home Farm” bring down fresh straw every day throughout Doris’s

illness. Just another thing I shall always remember the Rothschild

family for, and I think that was the last time straw was laid in

the High Street. |

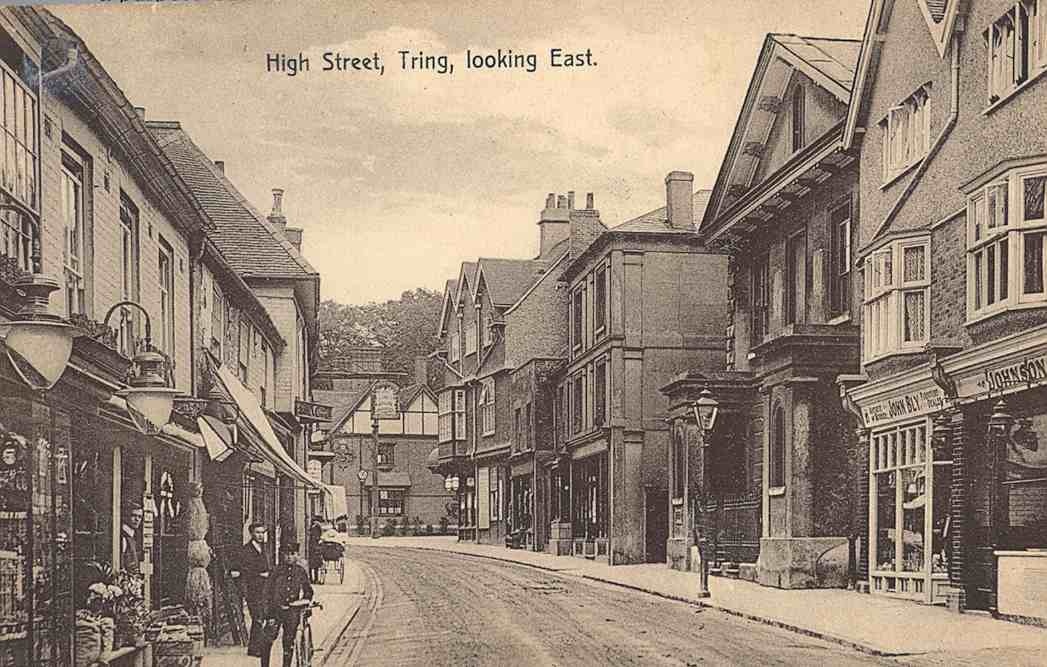

John Bly’s father’s antique shop is on the right of the picture,

next to the Tring Bank (Thomas Butcher & Sons).

The shop was pulled down in 1911 and later became the site of

the Midland Bank.

|

My father’s shop was one of the oldest

buildings in the High Street and we all lived above and behind it.

One

bedroom was built over a gateway leading to the yard at the

back, and also to the garden and coach house of the adjoining

property, which was the surgery and home of our local doctor.

In 1911 my

father’s landlord suddenly decided to pull

down the old shop together with that next door and rebuild. This put father into difficulty, but

fortunately the Old Brewery House with its yard and garden was empty and

only about three doors away, so into it we moved while the

rebuilding took place. This for me was wonderful; a big house, all

the old brewery buildings to explore and an immense garden, room for

rabbits, pigeons and, in fact, all creatures great and small.

1911 was a very hot summer. On the day of the great Agricultural Show in Tring Park,

while we were all at the show a terrible thunderstorm broke and a man was

struck by lightning and killed, which to me was awful and very

frightening. The Show was run under the very active support and

Presidency of Lord Rothschild. It was always held on the first

Thursday after August Bank Holiday and was known as the greatest one

day show in the country.

In 1913 a wonderful thing happened. After losing Dolly Grey father

didn’t buy another horse, but instead he bought a second-hand four-seater