|

|

|

The Bridgewater Monument. |

Slightly to the east of Aldbury lies the Ashridge Estate, once

the seat of the Duke of Bridgewater. In 1803, the Tring vestry

minutes record the Duke’s passing. His Grace’s fortune having

being spent constructing the Bridgewater Canal, the family seat,

Ashridge House ― according to the vestry minutes ― fell into

“decay to such an extent that in places the roof had become open to

the sky”. The entry goes on to record that at the time of

his death, the Duke’s canal revenues had made him a very wealthy man

and that he intended to rebuild Ashridge House on a very grand

scale, had death not intervened. Ashridge House, as it stands

today, was built between 1808 and 1825 by the architect James Wyatt.

In 1832, the ‘father of inland navigation’ was commemorated with the

erection of the nearby Bridgewater Monument, a 108ft tower built

overlooking the Grand Junction Canal.

The Tring summit ends at Cowroast lock, the odd name of which is

believed to be a corruption of ‘Cow Rest’, a relic from the days

when herds of cattle were driven through the Tring Gap to market in London. John Hassell observed that the spot was:

“. . . most erroneously named . . . Here we saw herds of cows

grazing, and observed a fresh drove of sucklers with their calves

coming up to remain for the night, and we found, upon enquiry, that

this inn [The Cowroast Inn] was one of the regular stations

for the drovers halting their cattle for refreshment; hence I should

suppose, the proper name is the Cow Rest, or resting place of those

animals, for along the road, and all the way through the breeding

and grazing parts of Bucks, Bedfordshire, and Northamptonshire,

there is a perpetual supply of cows passing to the capital . . .”

A Tour of the Grand Junction Canal in 1819,

John Hassell

A pair of L. B. Faulkner narrow

boats, southbound at Cow Roast lock. The nearer is carrying

coal.

The telegraph poles make a nice contrast with this earlier era of

human innovation.

――――♦――――

South of Cowroast, the Canal continues to follow the original course of the

Bulbourne, then, at Hemel Hempstead, of the Gade, of which the

Bulbourne forms a tributary. Both rivers powered numerous

water mills. When the Canal was built the Bulbourne and the

Gade were diverted into

it, with excess water being returned to the original river

beds across overflow weirs set into the canal bank. During its

early years, this extraction of

water for the Canal was to bring the Company into conflict with the water millers, particularly with the paper manufacturer

John Dickinson.

|

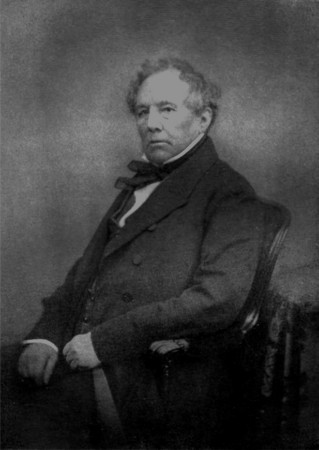

“John Dickinson thought it would be interesting to

become an astronomer, and built an observatory at

Abbot’s Hill in which he had a fine telescope set up.

When it was ready he entered it by himself to observe

the moon. He twisted the instrument about and aimed all

over the sky, but could see nothing. Swearing loudly, he

left the observatory and never entered it again. He had

in fact omitted to take the cap off the telescope.”

The Endless Web, Dame Joan Evans, 1955

|

John Dickinson

(1782-1869),

inventor,

paper manufacturer and

Fellow of the Royal Society |

|

|

Heavy traffic on the Canal resulted in more lockage water flowing down

it than had been anticipated, leaving insufficient to return to the

rivers for the use of Dickinson’s paper mills at Apsley; and, to

exacerbate the problem, that section of the Canal also wasted water through leakage. Dickinson’s complaint was not merely

about insufficient water

to power the mill wheel, but insufficient water to support the

pulping process. The 1793 Act required Company to build a

reservoir to compensate the water millers on these rivers for any

loss of water to the Canal ― expressed in the legal English of its

time, the gist of the relevant section reads:

“That before Brooks, Streams, Rivulets, Waters, Water-Courses, or

Springs, which now supply the Rivers or Streams of Gade, or Colne,

or the Berkhempstead River called Bulborne . . . . shall be taken or

used, for the Use or Supply of the said intended Canal . . . . be

diminished by Means thereof, the said Commissioners shall, and are

hereby authorized and required, to set out some Place or Places, as

near to the Line of the said intended Canal . . . . as they shall

judge most proper and convenient, a Piece or Pieces of Land, for the

making and forming a Reservoir or Reservoirs, for collecting

Flood-Waters sufficient to supply such Rivers, Streams, and Cuts,

with a Quantity of Water, equal at least to what shall be taken . .

. . for the Use or Supply of the said intended Canal . . . .”

Grand Junction Canal Act, 1793 (pp31-32)

― in other words the Company had by some means to put back, for the

use of the millers, the water it took out. But the reservoir

was not built and the long-running litigation that resulted led not

only to Dickinson being awarded damages, but the Company being

obliged to re-route the

Canal at Apsley to reduce the leakage. [6]

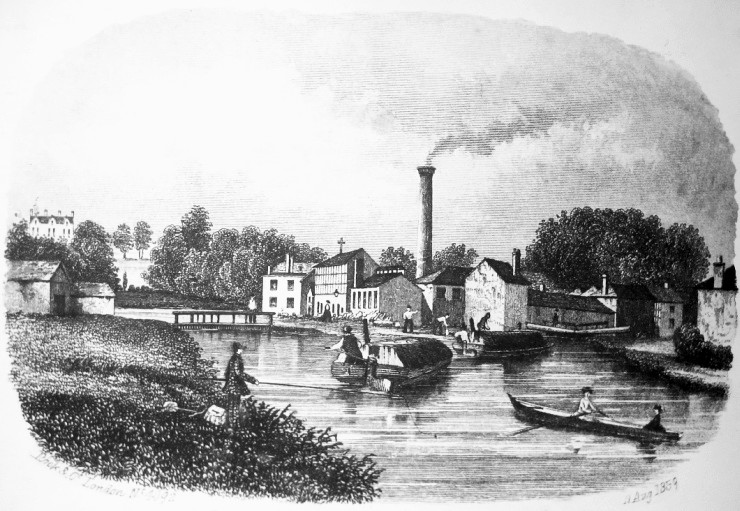

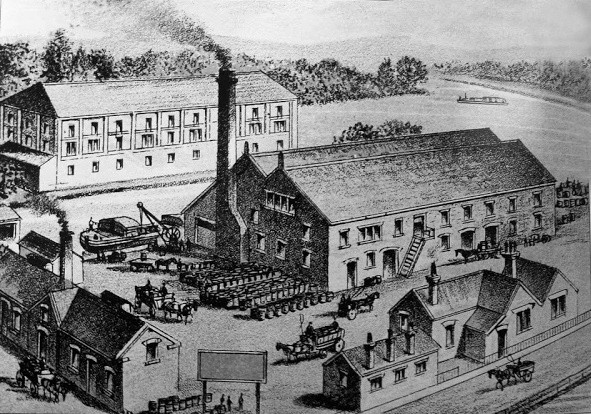

An artist’s impression of Nash

Mills, dated 1859.

As originally built, the Canal at this point followed a separate

course to the Gade, from above Apsley Mills to below Nash Mills,

where it rejoined the river after passing through a series of locks;

the deviation changed the course of the Canal to that of the river.

This required a further Act, which received the royal assent on 17th

March 1818, and the deviation opened that year:

“Dickinson had contracted to carry out the brickwork for the new

canal, and supervised it himself. He and a workman named Marks

had a violent quarrel over where a marking-post should be set in the

ground. They came to blows, and Dickinson was well and truly

beaten in the fight. The next day the workman expected to get

the sack; instead Dickinson gave him half a crown and later made him

sub-foreman at Batchworth.”

The Endless Web, Dame

Joan Evans, 1955

The damages awarded to Dickinson must have been substantial, for in 1816

the Board withheld the half-yearly dividend with the explanation

that (among other expenditure) the Company “had to pay heavy damages

unexpectedly awarded to Messrs. Dickinson and Longman, for a

subtraction of water from their mills on the Rivers Gade and

Bulbourne, between the years 1809 and 1815”. At the time

of Hassell’s visit to

Cowroast lock, this conflict with the paper

manufacturer (not to be the last) had recently been settled:

“On the right of the road at the Cow Roast, a lane leads to the

navigation, at the distance of about a hundred yards; there are two

cottages on the banks of the canal, which are called Water-gauge

Houses, one of which is inhabited by a servant of the Grand Junction

Company, the other is occupied by a person placed there by the Duke

of Northumberland. [7] Both of these persons keep an accurate

account of the height of the water at all hours of the day, and also

at the times of different boats passing the locks.

A deficiency in what is termed the river stream, or back water, for

supplying the bed of the River Bulbourne, which turns the wheels of

the paper mills upon that river, occasioned a protracted litigation

between the Company and Messrs Longman and Dickinson, who ultimately

obtained damages against the company.”

A Tour of the Grand Junction Canal in 1819,

John Hassell

Other than curing the leakage, the

Apsley deviation was to prove of benefit to Dickinson’s business in

another way, for the Canal now passed immediately adjacent to his mills, thereby

providing a ready transport link to other of his canal-side

factories and depots in London, and to the London docks.

However, Dickinson wished to have stronger control over the

water resources of the Bulbourne and Gade valleys and with this end

in mind he applied, in 1821, to have himself appointed an officer of

the Grand Junction Canal Company. His application having

failed, his wife duly confided to her diary:

“My Father . . . told us the Superintendent situation is to be

vested in the Select Committee so Mr. D.’s prospect has failed, a

thing we neither of us much regret.”

The Endless Web, Dame

Joan Evans, 1955

Trouble between Dickinson and the Company over the water

supply to his factories led to further litigation in 1851.

Three years previously, the Company had sunk a borehole adjacent to

Cowroast lock from which it extracted water for the Tring summit.

Because chalk is porous, it absorbs rainwater, in effect forming an

underground reservoir or aquifer that at Cowroast is maintained by a layer of

non-porous clay beneath it. Originally ― it was alleged ― this water found its

way into the Bulbourne, then flowed down the river valley to Dickinson’s

mills. After the new borehole had been dug, it was observed

that the level of water in a nearby well fell when it was being

pumped. This caused Dickinson to apply for an injunction to restrain the

Company from extracting water that he felt would otherwise be

available for the use of his mills. The court directed the eminent civil engineer William

Cubitt (1785-1861) to investigate. By taking careful

measurements in the Bulbourne when water was being extracted from

the borehole, Cubitt was able to demonstrate that the river level

did in fact fall at these times. Dickinson, having been granted a

perpetual injunction against the Company,

informed his sister that:

“This is not only a triumph, but a most important relief from

anxiety, because the costs on our side only have run up to £1700 and

upwards, and the [Canal] Company’s are at least as much.

This is the second lesson I have given

that rascally Company, and I should think it is the last time that I

shall have to fight them”.

The Endless Web, Dame

Joan Evans, 1955

But Cubitt’s method appears to

have been flawed, for some years later during a period of drought

that left the millers short of river water, the Company was still

able to pump water from their Cowroast borehole, thus proving that

their water came from another source. The injunction was set

aside by mutual consent, since when the Cowroast borehole (plus

another since added at Northchurch) has been of great

service in supplying the Tring summit during dry periods.

Canal scene at Dudswell lock (No.

48).

The rollers just visible behind the horse’s harness prevent the

towing rope from chafing.

From Cowroast, the Canal commences its

35-mile descent along the valleys of the Bulbourne, Gade, Colne and

Brent to its destination at Brentford, and in the course of its

journey negotiates 57 locks. The first section of the descent is

comparatively steep, with 33 locks encountered in the 15 miles to

Watford. The first is at the hamlet of Dudswell, which in

1798 was severed by the new waterway. Here, a prominent feature of

the canal

scene is ‘Mill House’, which has an interesting history

linked to the Canal.

The Company built Mill House to stable 20 boat horses, with

an adjacent cottage for a keeper, and leased it to Pickfords, who at the time had an extensive

canal carrying business. Their overnight fly-boat services

operated to strict timetables, which required fresh boat-horses to

be available at points along their routes. It is estimated that

during the course of the day up to 40 boatmen would exchange their

horses at Dudswell.

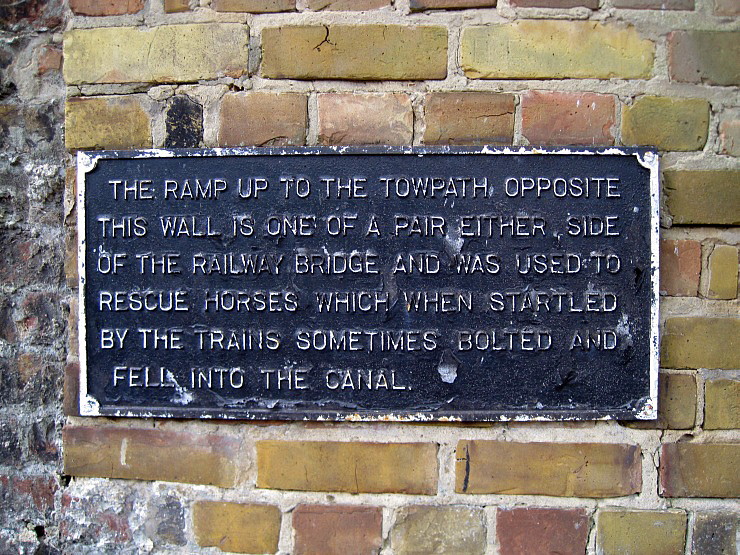

Boat horses were sometimes beautifully decorated. Their harnesses were fitted

with small brightly-painted rollers (just visible in the photograph

above) through which the tow rope ran

to prevent it causing chafing injuries, and in summer they

wore decorative cotton covers over their ears as protection against the irritating

flies. When hauling a barge, a boat-horse would often have a

metal bucket (its feed tin) left over its mouth to prevent it

stopping to graze on the towing path, for should it stop, the momentum

of the loaded barge was likely to pull the horse into the canal; the same

outcome could also result from the tow line snapping. Thus, at points

along the canal bank there were steps into the water to allow horses to be

recovered ― a few still exist. The horse’s feed tin, in common with

everything else associated with a canal barge ― drinking water can,

wash basin, cabin stool, headlamp, bucket, the walls inside the

cabin, the built-in furniture and doors ― was brightly painted with

pictures and posies.

|

|

This notice on the

Regent’s Canal

records another

cause of horses entering the water. |

In the late 1840s Pickfords gave up canal carrying in favour of the

railways, following which the Dudswell premises were taken over by

the Company’s newly formed Carrying Establishment which used the building until 1876, when

they too withdrew from the business. The next tenant was Albert Mead, a

member of the extensive Tring-based family who ran Tring Flour Mill

and the canal wharf at Gamnel Bridge. The Meads also operated a small

fleet of barges and had extensive business interests on the canal at

Paddington Basin. Albert Mead’s tenure at Dudswell lasted

until the 1890s, after which the building became the Dudswell Hay

and Corn Stores, a milling and mixing business that received

consignments of grain from local farmers, which were processed on

the premises and then offered for sale in various forms including

animal feed. During the 20th century, the Dudswell Mill passed

through a number of hands and uses, eventually becoming a warehouse

until, in 1986, it assumed the residential role it fulfils

today.

A

short distance to the south, the Canal reaches Northchurch where a

British Waterways borehole is located from which water can be back-pumped

to the Tring summit using equipment installed upstream at Dudswell and Cowroast

locks.

――――♦――――

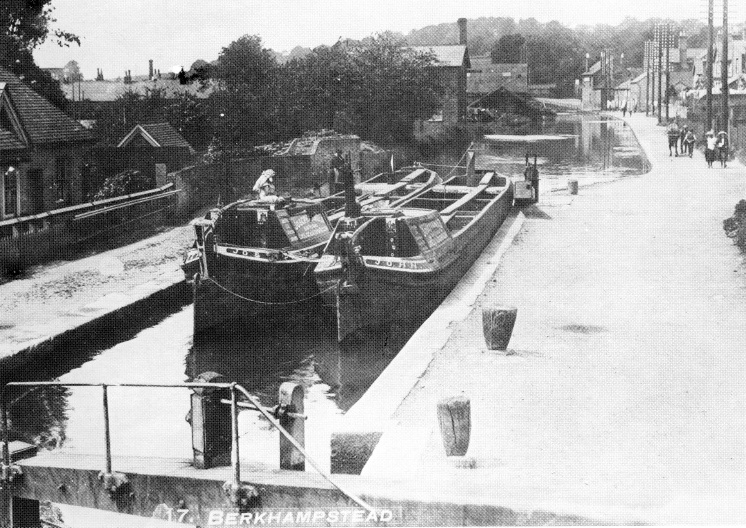

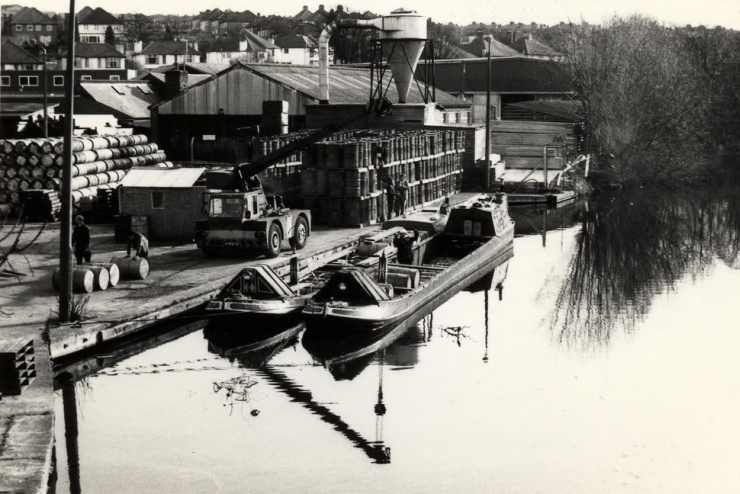

Approaching the Port of

Berkhamsted from the south.

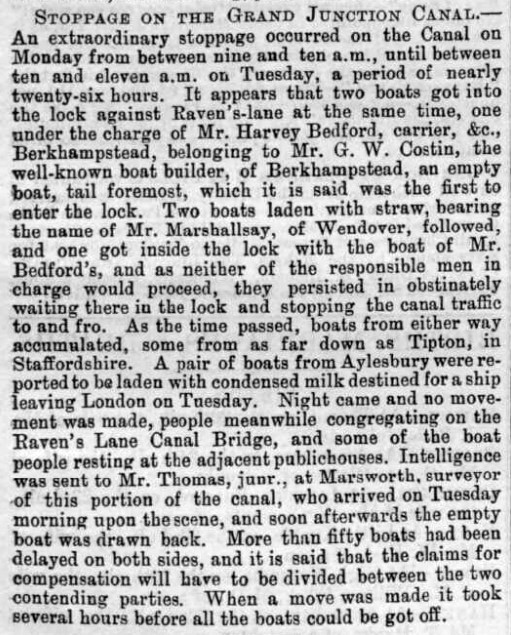

Stoppage at Berkhamsted, Buck

Herald, 1st March 1890.

To the south of Northchurch, the Canal flows into the ‘Port of

Berkhamsted’, or perhaps the former port, for of the eight working

wharfs that once served the town none now remain. [8] The section of

the Canal through Berkhamsted was opened in 1798. Castle Wharf,

between Ravens Lane and Castle Street, became the centre of the

town’s canal trade and it was this area that became known as ‘The

Port’. The town’s commerce then grew rapidly due to this

quicker and cheaper means of transporting the usual bulk

consignments of coal, grain, building materials and manure. Wharves, timber

yards, breweries, boat-building, and later a chemical works, and all

the people associated with these industries flourished as a result. Ironically, the

waterway was later to carry some of the

materials used in the construction of the London & Birmingham

Railway, which following its opening in 1838 captured much of the

Canal’s business leading to a decline in its fortunes.

Among the new businesses that the Canal brought to Berkhamsted was

boat-building. In 1799, the firm of Peacock & Willetts established a

boat-building business on the canal bank at Castle Wharf. Their

first craft, owned by William Butler, was launched in 1801 and

registered the following year in the Company’s Gauging Register. Named

Berkhamsted Castle after the ruined Norman castle that stands nearby,

she was the conventional length for a narrow boat ― 70 ft ― but at

14ft she had twice the beam, making her a river barge. [9] Gauging

records show that she drew 12 inches of water light and 49 inches when

loaded to 65 tons. When inspected she had on board “one

Fire Stove, one Pump, One Anchor and Cable, two Warps (or Hawsers),

one pair of Oars, three Sets, and two Planks”.

The Berkhamsted Castle was the first of 60 boats to be built in

Berkhamsted over the next 125 years. In 1826, the boatyard was

acquired by John Hatton, a boat builder, who appears in local

trade directories for at least the next 55 years. A further change

of ownership came in 1882, when the yard was acquired by William

Edmund Costin, later trading as W. E. Costin Ltd. Again, trade

directories record that he was a boat builder and coal merchant, who

traded at Berkhamsted for almost 30 years in premises described as

“dock, shed and yard, house and water house”. Costins built many of

the boats for the Aylesbury-based canal carrier John Landon & Co.

(later taken over by A. Harvey-Taylor). They were named after towns

in the South of England: Benfleet, Fulham, Blackwall,

Erith,

Guildford, Purfleet, Richmond and Westminster; the last of the

fleet,

the Hythe was launched in June 1909. Other large customers included

the canal carrier L. B. Faulkner of Linslade, who commissioned the

Vulture, Buzzard, Falcon, The Swan, Cygnet,

Dauntless, and White

City. The list goes on, with clients as far away as Birmingham — the

Bourne, Chess, Dane, Danube, Dart, Don, Dove, Isis, and

Wear were

built for the canal carrier, Thomas Clayton Ltd. Shortly before the

boatyard closed, boats constructed for carrying crude tar were built

for Fellows, Morton & Clayton. All these vessels were launched down

the company’s slipway sideways on, with the opposite bank being

sand-bagged.

A wide boat being launched

broadside on, this at Bushell Brother’s boatyard at Tring.

Boat-building ceased in Berkhamsted in 1910, and the premises were

then taken over by William Key & Sons, timber merchants, who became

established after supplying fencing for the London & Birmingham

Railway. The final owner, Bridgewater Boats, refurbished the old

warehouse as a modern dwelling and started a canal boat hire company

catering for the leisure industry. This business closed in 2002 and

the boatyard site is scheduled for redevelopment.

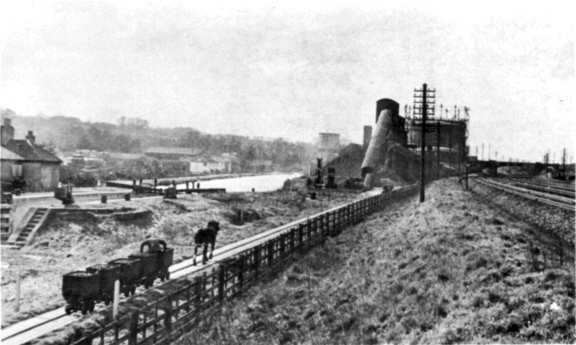

Berkhamsted

Gas Works ― Canal

to the left, West Coast Main Line to the right.

Castle Wharf also serviced ‘The Great Berkhamsted Gas, Light & Coke

Company’. Set up in 1849 to provide street lighting, the original

gasworks was built at the junction of Water Lane and the Wilderness.

Its deliveries of coal were by canal, via Castle Wharf, the gas company

despatching crude tar products to the London area in return. In 1906

the gas works moved to the triangle of land between the Canal and

the railway line east of Billet Lane, coal then being delivered via

a short access line from the railway sidings. Both gas works are

long gone, but a surviving memento of the first is ‘Adelbert House’

in Mill Lane, once the home and office of the Berkhamsted Gas, Light

and Coke Company’s manager.

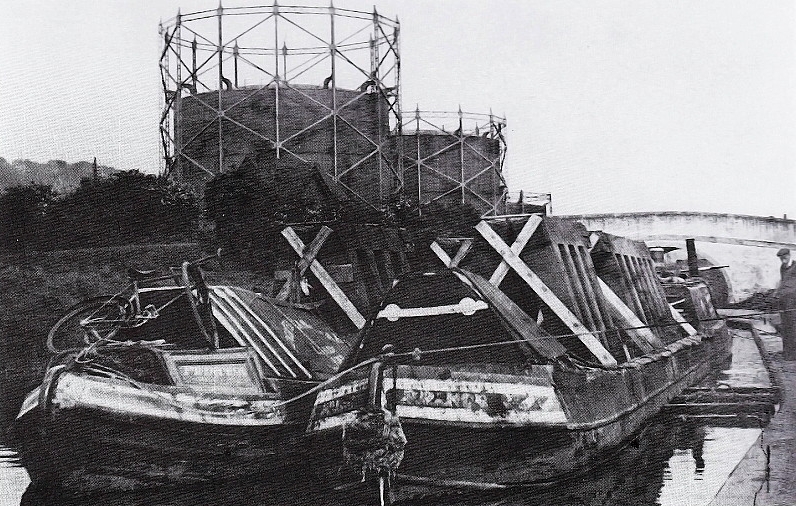

In 1990,

East & Son of Gossoms End, Berkhamsted, celebrated the founding of

the firm by Job East 150 years earlier. They have made a variety of

timber products including lock gates. Here gates have been loaded by

crane from premises into Prince and princess. The firm supplied 100

head gates and 102 tail gates for the New Hatton Locks in the 1930s.

The

gas holders of Berkhamsted Gas Light & Coke Co. are those in the

background.

The largest commercial operation in Berkhamsted to use the Canal was

the chemical business of Cooper, McDougall & Robertson,

manufacturers of sheep dip. This business was started by William

Cooper, a veterinary surgeon, who arrived in the town during the

early 1840s with very little to his name. He began to search for a

formulation that would combat scab in sheep, a type of mange caused

by the sheep scab mite and a condition for which there was then no

cure. By the early 1850s Cooper had developed an effective remedy

comprising arsenic and sulphur, and began its manufacture. So

successful was the product that business grew and with it the

factory premises, which eventually included a wharf where

barges discharged their loads of sulphur, arsenic and coal, and

loaded cases of powdered sheep dip for transportation to the London

docks.

In 1959, Cooper, McDougall & Robertson was acquired by the Wellcome

Foundation, and then in 1992 the French company Roussel acquired the

business and its Berkhamsted site. Having cost a fortune of

detoxify, the former industrial premises was sold and redeveloped

for housing.

――――♦――――

|

|

|

Boxmoor Wharf to

let: an advertisement from 1815 |

To

the south of Berkhamsted, the Canal continues its descent through Winkwell to Boxmoor,

following closely the course of the River Bulbourne.

Boxmoor Wharf was built by the ‘Box Moor Trustees’ with the proceeds

of the sale (in 1799) of common land at Boxmoor to the Grand Junction Canal

Company, the wharf’s income going towards the relief of the poor at

Hemel Hempstead and Bovingdon. [10]

Later in the century, the wharf became associated with the import of

wines and spirits:

“The best known of the lessees in the 19th century was Mr.

Balderson, who took over the lease in 1856. Henry Balderson was a

notable figure in the town; he was a dealer in coal, coke, stone,

corn, and timber. He was probably better known nationally as an

importer of wines and spirits, especially for his port and Olde

Stone Jar Whiskey. The former came in from Oporto in great barrels,

brought down from London by canal and then bottled at the Wharf. The

boats were called Mildred and Ellen. His son, Robert Henry, joined

the firm in 1890. There is no further record of the name after

1926/7, when it is believed that the business went into

liquidation.”

The Book of Boxmoor,

Hands and Davis (1994)

Boxmoor Wharf and dock

during Balderson’s tenure.

The wharf was taken over in 1947 by Rose’s of St Albans, who were

expanding their lime juice and lime oil refining business . . . .

“The unprocessed lime juice arrived by ship at London’s docks and

the casks were transported by barge down the canal to Boxmoor. Here

the juice was stored in huge oak vats, each holding up to 12,000

gallons. After a time, the clear green-gold juice was drawn off,

filtered and sweetened with pure sugar. It was finally bottled at St

Albans.”

L. Rose & Co.

What was known to boatmen as the ‘barrel run’ took ― on a clear run

― about 12 hours

from Brentford to Boxmoor Wharf. Rose’s was one of the last

companies to use the waterway commercially, ceasing their canal operations in

1981. The site is now occupied by a B&Q DIY store.

Boxmoor Wharf in its limejuice

days. By this date the dock had been filled in.

Another canal-side business based at Boxmoor was Foster’s Saw Mill,

which stood on the site of the present day River Park Gardens.

A mill had stood at Boxmoor since the 18th century, when it was

originally a shoe-heel and clog factory, powered by a water-wheel

driven by the River Bulbourne which ran through the premises.

This was later replaced with a steam engine. In 1930, the mill

was taken over by the firm J. W. Ward of Bourne End. Many

local people were employed there in the preparation and supply of

timber for building, fencing, joinery and even musical instruments.

The mill burnt down in 1967.

――――♦――――

|

Narrow boats at Apsley Mill.

The butty on the left (Kate) is loading finished products, probably

for London. The two on the right appear to be loaded with raw

materials for pulping. In 1890 Fellows, Morton and Clayton

contracted to operate the Dickinson inter-mill service. In

1897 they had replaced horse-drawn boats with the steamers Countess

and Princess together with the butties Maud and May; they were

replaced, in 1910, with Alice and Kate. |

At Two Waters, the River Gade flows into the Canal just above Boxmoor Wharf.

From this point to Rickmansworth

the history of the Canal becomes closely associated with that of paper

manufacturing:

“TWO WATERS, a

village in Herts, two miles S.S.W. from Hemel Hempstead, is

pleasantly situated at the union of the river Gade with Bulbourne

Brook and adjoining the Grand Junction Canal . . . . and in the

village is the elegant little cottage of Henry Fourdrinier Esq.

Two Waters, and its vicinity, have long been noted for the number of

paper mills erected on the sides of the stream; but that belonging

to Mr. Fourdrinier is more particularly worthy of notice, for

containing the invention of manufacturing paper by machinery.

By this machine, and appendant apparatus, every part of the process

is conducted without the intervention of manual labour; and it

cannot fail of exciting surprise in the spectator, on beholding the

rag first washed, then beaten or reduced to pulp; and, lastly,

conducted through pipes to the reservoir of the machine, which

constantly feeds itself, and, in a very few seconds, produces a

paper so perfect in all its parts, that it is wound off upon a reel,

exactly like a web of cloth.”

A Pocket Companion for the tour of London and its

Environs (1811)

A short distance to the south, the Canal begins its journey past the sites of the former John

Dickinson paper mills. In 1819, Hassell described Apsley Mill as:

“. . . .occupying a large space of ground, and rather resembling

a village than a manufactory . . . . Such of our readers who have

never seen the process of manufacturing this useful article, will be

highly gratified in visiting a paper mill. The machinery of this

mill is entirely worked by steam, from the washing of the rags to

the keeping of the pulp in a state of motion, while taken into the

mould from whence it is placed between flannels until it sets; and

afterwards it is pressed, dried and sorted for the market”.

A Tour of the Grand Junction Canal in 1819,

John Hassell

The paper-making process is indeed of interest and today is

demonstrated for the benefit visitors to the ‘Paper

Trail’ Museum at Frogmore Paper Mill, Apsley. Other than the Museum, little now remains of the

site as Hassell saw it, for following company acquisitions and closures

during the 1990s the former Dickinson paper mills received the attention of the

residential property developer.

Irascible though he was, John Dickinson was no fool [11]

and he and the Company were to have a close business relationship

over many years, hostile at times, but overall to their mutual

benefit. Originally the firm owned its canal boats, but in

1890 the canal carrier Fellows, Morton and Clayton contracted to

operate Dickinson’s inter-mill service. [12] FMC

replaced Dickinson’s horse-drawn boats first, with steamers, and

then in 1927 with motor boats. These were used to convey the

firm’s products to London, with return cargoes of raw materials such

as waste paper, rags, esparto grass, wood pulp, chemicals and china

clay. Following their conversion from water to steam power,

large quantities of coal were also shipped to the mills from the

Warwickshire coal fields. During the 1870s and 80s:

“Coal came by boat. At Nash Mills it had to be wheeled from

the wharf on the canal, over the Mill Head Bridge and down the

garden path on to the tip, a run of from eighty to one hundred feet.

A gang of six men was made up to wheel in the sixty tons from two

boats, the pay being 4d. per ton and thirty-six pints of beer (drawn

from two barrels kept on the premises), this working out to about

4s. plus six pints per man. The other mills allowed beer for

this work but were less generous in quantity.”

The Endless Web, Dame

Joan Evans, 1955

Among its many exhibits the Paper Trail Museum displays a

“Register of boats and coal arrival 7/1933 to 26/6/1942” at

Apsley Mill, which records pairs of narrowboats delivering around 53

tons of coal every two to three days:

“Most of the coal-boat skippers were Number Ones ― working

owners, whose wives and families were the crew. They all lived

aboard, in the tiny cabins of the leading and towed ‘butty’ boat,

the round trip from Warwickshire taking ten to twelve days. . . . It

was 1927 before the first Number One acquired a motor-driven boat

and cut the round trip time to four days.”

Canal Memories, pub.

Dacorum Heritage Trust (1999)

|

Discharging coal at Apsley

Mill. The Dickinson paper mills in the Apsley area closed in

1999, and the land has since been redeveloped.

Nash Mill was sold to the Sappi Group and continued to

make paper until 2006, when it too closed. |

During the 1960s the paper mills switched to oil-fired boilers and

coal deliveries ceased.

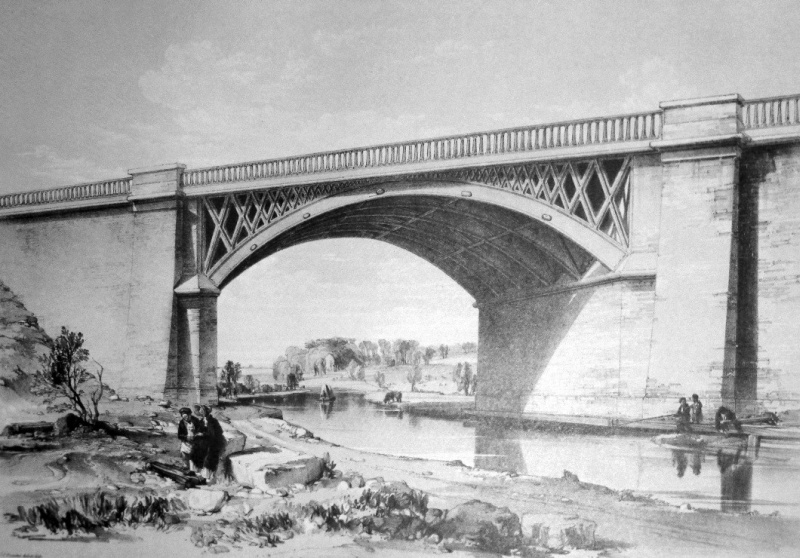

Just south of Apsley the canal passes the former site of Nash Mills,

another of Dickinson’s paper mills. During the construction of

the London & Birmingham Railway, the artist John Cooke Bourne made a

series of sketches of the railway under construction that included

an illustration of Robert Stephenson’s fine skew railway bridge,

which crosses the Canal near to this point. It is near the

location of this bridge that the southern end of the 1818 deviation

returns to the course of the original Canal.

Nash Mills Railway Bridge and the Grand

Junction Canal, by John Cooke Bourne.

――――♦――――

Continuing south of Nash Mills railway bridge, the

Canal reaches

Kings Langley and the site of Toovey’s Flour Mill. A mill stood here

on the River Gade long before the Canal arrived to pass close by. Following a dispute with Thomas Toovey, the

miller, over water rights, the Company bought his mill and leased it

back to him. The family-run business kept pace with

technical developments, installing, in 1894, steam power and the new

‘roller’ milling process by which grain is ground by a succession of steel

rollers (rather than with traditional millstones) in a gradual

reduction process, a system that

continues in use today. The firm maintained its own wharf and canal

boats, which carried imported grain from Brentford to the Kings

Langley mill. Records show that the Tring boat-builder Bushell

Brothers

constructed a pair of horse-drawn ‘wide boats’ (11 ft beam), the Langley and the

Betty, for Toovey in 1916.

‘Golden Spray’ was Toovey’s top grade flour and a canal boat

registered in 1922 in the name of T. W. Toovey carried that name. The firm continued in business until 1978 when it went into

voluntary liquidation. The machinery was then sold by auction and the

mill demolished.

|

The board for’ard of the cabin

proudly proclaims the Langley to be a product of Bushell Brother’s,

Tring Dockyard, where she is pictured.

Bushell’s received a repeat order in 1922, which resulted in the

‘Golden Spray’. Both were wide boats. |

Photo: meophamman

A short distance to the south of Toovey’s Mill stood the factory of

A. Wander Ltd., manufacturers of the malted dairy drink ‘Ovaltine’.

Ovaltine ― formerly ‘Ovomaltine’, from ovum, Latin for egg, and malt, originally

its main ingredients ― was created in the 1860s by Dr George Wander,

a Swiss chemist, to exploit the nutritional value of malted barley. Its success was such that the product was marketed internationally.

|

|

|

Discharging coal at

the Ovaltine factory |

The manufacture of Ovaltine commenced at Kings Langley on a small

scale in 1913. Sales grew and a much larger factory, the fine façade

of which remains, was built on the site between 1924 and 1929.

Erected by C. Miskin and Sons of St Albans, oddly, the architect of

this art deco masterpiece is unknown. To

ensure that supplies kept pace with the company’s growing demand for

barley, eggs and milk, two nearby farms were bought to provide Ovaltine’s natural ingredients. Known as the

‘Model Poultry’ and ‘Dairy’

farms, they were rebuilt in precise imitation of the farm that King Louis XVI

of France built for Queen Marie Antoinette, and featured

regularly in the firm’s advertising to promote their drink’s

wholesome qualities.

The canal-side location of Wander’s factory allowed the coal

needed to fire its boilers to be delivered direct from the

Warwickshire collieries, narrowboats completing the 10 to 14 day

round trip in a continuous circuit. In 1925, the firm introduced its

own fleet of boats, the first pair, the motorboat Albert and the

butty Georgette, entering service in January 1926. At its peak, the

Ovaltine fleet totalled seven pairs of narrowboats, but by 1954 it

had reduced to 3 pairs and contractors were increasingly delivering

the coal. Eventually the company switched to oil, the last delivery

of coal being made in April 1959.

In 2002, production of Ovaltine was transferred to Switzerland by

its then owners Novartis and the factory was sold for residential

development, which was described in the advertising as

“Luxury apartments and stylish townhouses on a popular Art Deco

development with historic charm”.

Both Toovey and Ovaltine made use of the Kings Langley section of

the Canal towards the end of its commercial life, but in

its early days the Canal served a much more agrarian society, as

was recorded by Arthur Young, an eighteenth century writer on agriculture:

|

“Mr. Newman Hatley, a considerable farmer at King’s Langley, has

opened a trade upon the canal, in order to give him a greater

command of manure for his farm. I was solicitous to know at what

expense a barge could be kept constantly in employment: he favoured

me with the following particulars.

“The barges carry 60 tons; and their construction costs £262-10s. They are navigated by a bargeman and his boy, and one other man,

with three horses: the bargeman and boy cost £2-12s-6d. a week; the

man 17s. A voyage takes ten days; locks and dues on a load of manure

amount to £5. Hay pays three farthings a mile per ton; the distance

extends 25 miles. Corn and other goods, 1½d. I was informed, that a

barge-load of night-soil [13] and sweepings of streets, in a compost,

costs at London £12.”

The Agriculture of Hertfordshire,

Arthur Young (1804) |

――――♦――――

To

the south of Kings Langley, the canal passes under the M25 viaduct

to reach lock 74, adjacent to which is the former ‘Lady Capel’s

Wharf’, a name that stems from the Capel family, earls of Essex. In

1546 Henry VIII granted the Manor of Cassiobury to Sir Richard

Morrison, who, with his son Charles, built a large house and

extensive gardens. In 1627 Charles’s daughter, Elizabeth, married

Arthur Capel (1610-1649) and the estate passed into the Capel

family. At the Restoration, King Charles II made Arthur Capel 1st

Earl of Essex.

A river barge at Hunton Bridge

― an early colour photograph (Vivex) from the 1930s.

The 4th Earl, William Anne (sic.) Capell (1732-99), was one of the

noblemen on the Grand Junction Canal Company’s board, and at his insistence the

Canal

was widened and landscaped where it passed through his estate. The

name ‘Lady Capel’ persists, although the wharf, which was a mile or

so north of the present park, is long gone. It was here that

large shipments of coal were landed due to a monopoly enforced by

the early Canal Acts, which barred coal from being conveyed

any further south. The 1793 Act makes clear the harsh penalties

awaiting any boat owner intent on breaking the monopoly:

“. . . . the conveying of Coals from the Collieries of

Warwickshire, Staffordshire, Leicestershire, and Derbyshire, by the

said intended Canal, to the City of London, may be detrimental to

the Coasting Trade of this Kingdom, by diminishing the Consumption

of Coals brought to the Port of London by Coasting Vessels; be it

therefore enacted, That no Coal, or Culm, or Cinders burnt from Coal

or Culm, which shall pass along the said intended Canal and

Collateral Cuts, or any Part thereof, shall be conveyed nearer to

the City of London than the Mouth of the intended Tunnel at Langley

Bury, in the County of Hertford, by any Barge, Boat, or other

Vessel, on Pain of Forfeiture of every such Barge, Boat, or Vessel,

and of all such Coal, Culm, or Cinders, as shall be on board the

same, and also on pain of forfeiting the Sum of Fifty Pounds by the

Owner or Owners of every such Barge, Boat, or Vessel . . . .”

Grand Junction Canal Act, 1793

In the event the Canal did not follow its intended path through the

“Tunnel at Langley Bury”, and the boundary of the coal monopoly was

transferred to the north-eastern edge of Grove Park, which is where

Lady Capel’s Wharf was located. [14] The monopoly was later relaxed to permit the

transit of 50,000 tons, a weight limit that was later removed, but subject

to the payment of ‘coal duty’ ― which in 1831 was £1-1s per ton ―

and Lady Capel’s Wharf became the nearest point at which coal for

Watford could be offloaded without payment of the duty. Officials

were stationed at the boundary marker to collect the duty and to

record the tonnage that passed.

Coal duty was introduced in the 17th century [15] as one of a range of

duties levied on some types of goods entering the Port of London and

certain surrounding areas. The proceeds were used to help finance

rebuilding following the Great Fire of London (1666). Buildings

damaged or destroyed in the fire that benefitted from the duty

included Saint Paul’s Cathedral and many of the City’s churches, the

Guildhall, the City’s markets and Newgate Prison. Eventually

numerous of the Capital’s public works and causes came to be funded

in this way such as (in the 19th century) the construction of the

Victoria, Albert and Chelsea Embankments, Northumberland Avenue,

Hyde Park Corner and the northern and southern outfall sewers (which

were largely responsible for wiping out cholera in London). When, in 1861, the area for the coal duty was altered to coincide

with the Metropolitan Police District, the coal duty boundary was

transferred to Stocker’s Lock near Rickmansworth. Coal duty was

eventually abolished in 1890.

――――♦――――

At

the north-eastern edge of Grove Park, the line

followed by the Canal today lies to the east of that authorised

originally by Parliament. The intention had been to cross the River Gade on an

aqueduct near to Kings Langley and then to drive a tunnel through

the high ground behind Langleybury House, then to pass down the western side

of the Gade Valley and descend into Rickmansworth through a

flight of locks. It is possible that this route was influenced by a wish

to avoid confrontation with the influential

owners of the Langleybury, Grove and Cassiobury estates that lay in

the river valley, then the domains of Sir John Filmer and the Earls

of Clarendon and of Essex respectively. But equally, driving a

tunnel at that time was, as Braunston and especially Blisworth

were to demonstrate, an engineering challenge fraught with risk.

The alternative line down the eastern side of the Gade Valley would

not only avoid the need for the aqueduct and tunnel, but take the Canal nearer to

Watford. At the General Assembly of November 1797 ― with the experience of tunnelling at Blisworth

by then before

them ― the Committee explained the change of line in the Gade Valley, stating simply that “the importance of avoiding a tunnel, few will now

dispute”. [16] And none did.

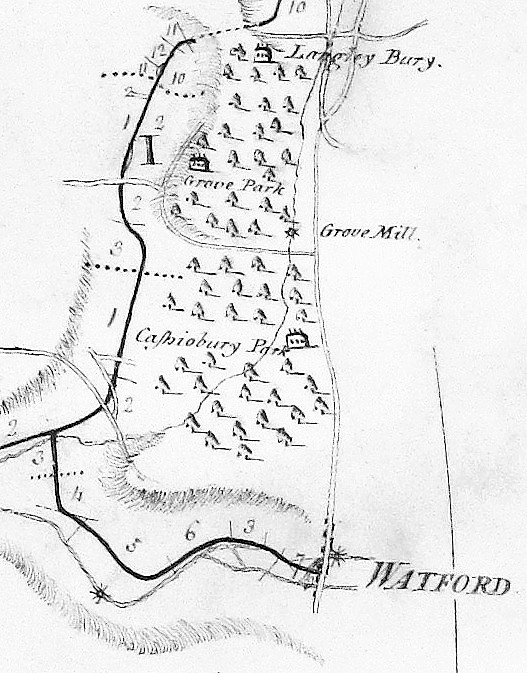

The intended line of the

Canal ran down the western side of the River Gade

Valley

― the line

taken followed the Gade, shown at the centre of the map

A contract to drive the Langleybury tunnel having already been let,

the Company Chairman, William Praed, entered into negotiations to

purchase land for the deviation that is followed today. Writing some

years after the event, Arthur Young had this to say:

“The proprietors of the navigation proposed to tunnel under

Crossley-hill, but the Earl of Essex, actuated by motives of

patriotism becoming his high rank, and consonant with his

philanthropy, agreed that the navigation should pass through his

park, which it accordingly does; great expense in tunnelling was

thus saved to the proprietors, and of freight in course to the

public.”

General View of the Agriculture of Hertfordshire,

Arthur Young (1804)

. . . . and John Hassell was also to join in the

kowtowing:

”Ready permission was granted by the present Earl of Clarendon,

and the late Earl of Essex, to allow this great national undertaking

to pass through their respective parks; and when we find the

opposition that the Duke of Bridgewater was continually receiving,

from parties, through whose premises he was unavoidably often

obliged to pass his navigable canals, it must stand as a monumental

record, and example of the urbanity and amor patriæ, these

distinguished noblemen exhibited for the weal of their country.”

[17]

A Tour of the Grand Junction Canal in 1819,

John Hassell

No doubt these patriotic landowners received adequate financial

compensation; in fact the Earl of Essex held out for a better price,

which he received. Their Lordships did, however, insist on clauses

in the Act that authorised the altered route, to stipulate that the

sections of canal that ran through their domains be made as

attractive as possible. And so they were and now form a delightful walk.

Cassio Wharf, at the southern end of Cassiobury Park, was the

nearest wharf to Watford; today the site is occupied by a marina. A

branch canal into Watford and onwards to St. Albans was in fact

authorised by Parliament in 1795, but in the cold light of day ― despite much agitation from the

citizens of both towns ― it must have appeared to the Company that the

costs of building and maintaining the Watford/Saint Albans branch outweighed

its likely

benefits:

”An act passed for another canal from St. Albans, to join the

Grand Junction below Cassiobury-park; but for want of power to raise

£17,000 by subscriptions, nothing has yet been done towards carrying

it into execution.”

General View of the Agriculture of Hertfordshire,

Arthur Young (1804)

Plans for the 2-mile

Watford Arm show that it would have departed the main line in the

vicinity of Croxley (lock 79) to terminate in a basin to the north of

the site now occupied by Bushy Station. Barnes surveyed the 9-mile

extension to St. Albans in 1792. This he planned to commence from the

vicinity of the Watford basin, then, following the course of the

rivers Colne and Ver (sections of each being canalised), would

terminate in a basin in the Ver valley about 1-mile to the

south-east of St. Albans Abbey.

In passing it is worth mentioning that other proposed branches for

which Acts were not obtained were to Chesham, Dunstable and Hemel

Hempstead. The 1-mile branch canal to Daventry was authorised by

Parliament, but not proceeded with; it is still discussed today, as

is a once-mooted branch from the locality of Fenny Stratford to

Bedford. In none of these cases does the business case appear to

have been sufficiently robust to justify the costs of overcoming

resistance from landowners and of construction.

――――♦――――

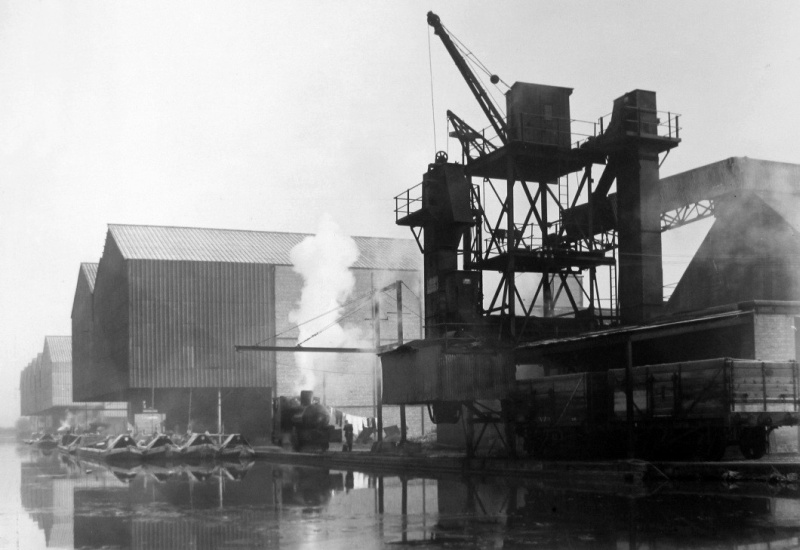

Croxley Mill

At the southern end of the Gade Valley the

Canal reaches Croxley and further territory once occupied

by John Dickinson’s paper-making empire. In 1830, Dickinson opened a

canal-side paper mill on Common Moor, which by 1838 was producing 14 tons of paper

a week. Papermaking was eventually transferred to Croxley Mill from Apsley

and Home Park (Nash Mill continued to manufacture specialist papers)

and by 1894 weekly output at Croxley had risen to 140 tons.

Croxley mill was mostly steam-powered, the coal to fire its furnaces

being transported by canal. Writing in 1896, Lewis Evans [18] gives an

interesting description of the factory’s coal deliveries:

“The actual buildings of the mill cover an area of about 24,000

square yards, or nearly five acres. The power for driving the

machinery is almost entirely derived from steam engines . . . .The

coal shed occupies an area of 200 ft. by 50 ft., and is capable of

holding 4,000 tons of coal . . . . The coal is unloaded from boats

on the Grand Junction Canal by a kind of dredging machine, which

delivers it to an endless chain-conveyor running in a trough along

the top of the shed. There are gratings in the bottom of this trough

through which the small coal can drop, the lumps which are too big

for the mechanical stokers passing on to the other end of the shed. The chain returns along the shed in an underground tunnel, the coal

for the boilers dropping on to it through openings in the floor, and

so being carried along for delivery to a second chain, which conveys

it over the mill-tail to the chimney, where it is elevated to a

third chain passing along the top of the boiler-house. This chain

distributes the coal down chutes to feed the mechanical stokers on

the boilers, the ashes and clinkers being carried out of the house

by the returning chain.”

The Firm of John Dickinson & Co. Ltd.,

Lewis Evans (1896)

Croxley Mill depended largely on the Canal not only of supplies of

coal from the Midlands, but for its but raw materials brought up

from the London Docks by barges and lighters and for the export of

its finished products:

“Though the mills were all established before the age of

railways, Mr. Dickinson with his usual forethought chose for his

enterprise a locality provided with excellent water-carriage, and

though the London and North Western Railway now passes close to

three of the mills, and one of its branch lines near to the other,

water-carriage is still found to be the cheaper and cleaner, so that

the greater part of the traffic of all the mills is even now carried

on by means of the GJC, on which there are quite a fleet of boats

employed in bringing coal and materials to the mills, and in taking

away paper and stationery. These boats each carry about twenty-five

tons at a time, and every evening paper leaves the mills by them,

and is delivered in London next morning at six at the company’s

warehouse, Irongate Wharf, Paddington.”

The Firm of John Dickinson & Co. Ltd.,

Lewis Evans (1896)

But progress gradually overtook the leisurely pace of canal

transport. In 1937, articulated lorries took over the Apsley to

London run to collect esparto grass [19] and wood-pulp from the docks,

while the inter-mill barge service ceased in 1947. Coal deliveries

by canal continued until 1970, when Croxley switched to oil firing.

A Commer articulated truck in John

Dickinson livery pictured at Tring Dockyard where Bushell Brothers

had built the

bodywork.

――――♦――――

“Owing to the heavy rain, the water has overflowed the banks of

the river Colne and Gade, so that the meadows in the neighbourhood

of Watford and Rickmansworth are completely covered, and a great

quantity of hay is washed away. A barge belonging to Mr. Moses

Robinson, of Birmingham, was driven on the bank of the Grand

Junction canal, about a quarter of a mile from the town of

Rickmansworth, on Friday morning, and instantly went to the bottom.

It was loaded with iron bedsteads. A woman and two children very

narrowly escaped a watery grave.”

Jackson’s Oxford Journal,

3rd July, 1824

Rickmansworth stands at the confluence of the rivers Gade, Chess

(which flows into the town from Chesham to the north), Colne (which

flows into the town from Watford) and the Grand Junction Canal,

which, in 1796, arrived from the south to establish a link with the

Thames at Brentford. Local businesses soon began to use the

Canal, especially when a short branch was constructed to a wharf

just off the town centre. A century later, Wilson’s

Imperial Gazetteer of England and Wales described Rickmansworth

as a small town with:

“. . . . a railway station, a banking office, a good inn, a

timbered market house on pillars, a church, Baptist and Wesleyan

chapels, an endowed school with £24 a year, alms-houses with £10,

other charities £32, an extensive brewery, a silk mill, four paper

mills, cattle fairs on 20 July and 24 Nov., and a fair on the

Saturday before the third Monday of Sept.”

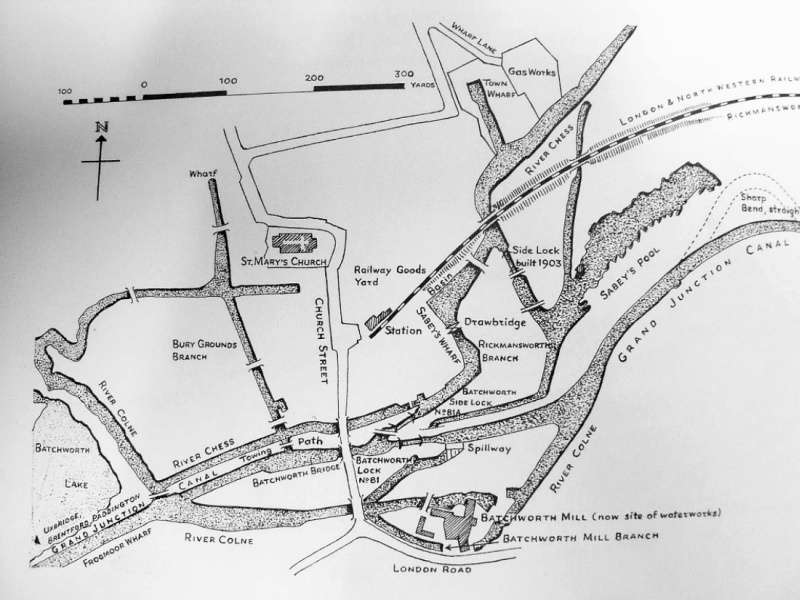

Waterways (shaded) at

Rickmansworth c.1870.

The railway, brewery and the paper mills referred to all benefitted

from links to the Canal, as did a bakery and, later, a boatyard.

The railway was the Watford & Rickmansworth Railway. Opened in 1862,

the line was never profitable and even less so when, following the

arrival of the Metropolitan Railway in 1887, the town was

connected directly with London. [20] Electrification in 1927 didn’t

ensure the line’s future; it

closed to passengers in 1952 and to freight in 1967. The railway’s

Rickmansworth terminus and goods yard, which was located opposite the parish

church, included a freight interchange siding with the Canal.

Salter’s brewery met with more success than the railway. The

Salter family’s connection with brewing dates from the 17th Century,

but it was only when Stephen Salter took over the business in 1750

that it began to grow. His nephew, who succeeded him, paid for

the River Chess to be made navigable for some 500 yards to the

firm’s brewery and maltings. Opened in 1804, Salter’s Cut [21] joins the Canal through a lock adjacent to Batchworth

Lock. Its main traffic was barrels of beer for Uxbridge with

the empties in return, although grain for malting and coal were

probably landed there as well. Besides

serving the brewery, the cut also served Town Wharf, the Rickmansworth gas works and a gravel pit

(Sabey’s Pool). [22]

In 1820, a short section of the River Colne just to the south

of Batchworth Lock was also canalised and used to convey shipments to Batchworth Mill.

The mill was used originally to spin cotton, its

machinery being powered by a waterwheel driven by the river.

Following the Canal’s arrival, there began a long-running dispute

over water levels at Batchworth. In 1809, the Company bought

the mill to obtain its water rights before selling it on, ex water

rights. In 1818, the mill was bought by John Dickinson and

converted to a ‘half-stuff’ mill, one in which rags and other

materials were prepared for turning into pulp at Dickinson’s other

mills, the output being transported to them by canal. But it

seems that the disputes over water continued until 1825, when a stone obelisk was erected in a pond to

act as a water gauge, the Company being liable for compensation

should the water level fall below a mark on the gauge. The

obelisk, which still stands, records the agreement made between the Company, John

Dickinson and R. Williams of Moor Park, who was the landowner. In 1886, following

the expansion of Croxley Mill (which by

then covered 16 acres), the smaller Dickinson mills became redundant

and Batchworth rag mill was sold and later demolished, the cut to

the mill being filled in 1906 when the London Road was widened.

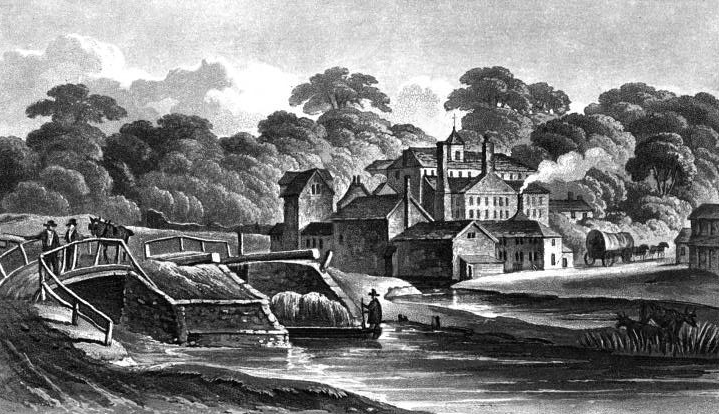

John Hassell’s sketch of

Batchworth locks and mill c.1819. Salter’s

Cut departs under the bridge on the left.

The mill was demolished

in the early years of the 20th century.

It is unusual to find a bakery served by

its own canal, albeit of a mere 300

yards in length, but such was the case at Rickmansworth. Taylor’s

Cut ran from a point just below Batchworth Bridge to a wharf

situated in the grounds of ‘The Bury’, the principal manor house of

the medieval manor of Rickmansworth. In 1843 The Bury was bought by

John Taylor, a coal and coke merchant who developed interests in

flour, grain and baking. Taylor built a cut, which passed in front

of the manor and nearby stable block to a wharf. Here, he unloaded

barges, their cargoes being stored in parts of the manor house that

he put to use as a warehouse ― unsurprisingly, the premises

are reported to have

deteriorated seriously by the time of his death in 1868.

Before leaving Rickmansworth, one further business should be

mentioned, that of W. H. Walker and Brothers, which besides trading

in timber, building materials, coal and coke, also ran a boat

building and repair yard. The firm were based at Frogmore

Wharf, now the site of a Tesco supermarket. During its years

in operation (1905-64), the boatyard became one of the canal network’s most

successful builders, launching 212 new boats and repairing over 600 others. Walkers specialised in wooden construction,

[23] building boats for,

among others, the canal carriers Fellows Morton and Clayton and the

Grand Union Canal Carrying Company, and for the manufacturing firms

of Cadbury of Bourneville and Wander (Ovaltine) of Kings Langley.

Batchworth Lock and the

entrance to Salter’s Cut on the left (a nice little tea shop exists

in between).

――――♦――――

|

|

|

The Stocker’s house and the London

Coal Duty marker.

“House. 1861-2. Built for the

City of London Corporation as a residence for its Collector of the

Coal Dues on the Grand Junction Canal. Stock brick.

Shallow hipped slate roof. 3 bays. Tall 2 storey front

with steps up to central entrance with a panelled door and

rectangular fanlight all in a rebated reveal. Large glazing

bar sashes in reveals.”

Grade II listing ― English National

Heritage description (extract) of Stocker’s House. |

South of Rickmansworth, below bridge 175, stands Stocker’s House, built in 1861 for the Collector of Coal Duties when the

boundary was relocated from its original position at The Grove near

Watford. This splendid Victorian dwelling suggests

that considerable status was attached to the Collector’s role. The

actual point at which duty became payable is designated by ― in the

words of English Heritage ― a “City of London Coal Duty Marker.

1861. Cast by H. Grissell, Regents Canal Ironworks. Cast-iron square

pier, one and a half metres high, painted white”. Both marker

and house are Grade II listed monuments.

Black Jack’s lock (No. 85) and watermill (now a guesthouse) lie a

couple of miles further south. The story behind the name is that the

mill and lock were named after a black slave who was bought and sold

with the land. With his donkey and cart, Black Jack delivered to its

customers the flour ground in the mill.

Nearby, at West Hyde, is Troy Cut, a 1,000-yard branch off the canal

built to serve Troy Mill. When milling ceased, the cut was

used to ship sand and gravel from nearby pits, now worked out. Indeed, the section of the

Canal between Rickmansworth and Denham is

lined with numerous worked-out gravel pits, now flooded and the

haunt of wildlife, fishermen and the occasional marina. And it was

in one such pit, during the 1950s, that the British Transport

Commission, who then ran the canal network, scuttled many redundant

narrow boats. . . .

. . . . an extract from the Inland Waterways Bulletin for

December, 1959, tells the story:

“We have more information about the sinking of narrow boats in

Harefield Flash . . . . Further investigation has disclosed that not

six boats have been sunk, but twenty-four. None of these appear to

have been offered for sale; though a firm of carriers inform us that

they might have purchased several, and the demand for converted

narrow boats is now so great that, for better or for worse, almost

any craft that will float at all, can be sold. British Waterways

themselves keep a list of applicants for boats suited to conversion.

Instead of offering the boats for sale, British Waterways apparently

paid the owners of the water where the sinkings took place, a

substantial sum, in the same way that payment is made for the

privilege of using land as a rubbish dump; and that they paid also

for a breach to be made, and later repaired, in a dyke, 20’ wide and

3’ high, which separates the subsidiary flash (normally an isolated

lake), from the main flash, which is accessible from the canal. The

boats were towed through this temporary channel, and then sunk right

across the subsidiary flash, like the fleet at Scapa Flow. Finally,

all these operations appear to have been carried out at a week-end,

on overtime. One can perhaps surmise why.”

Recent research suggests that over 50 boats share this watery

resting place including Daisy, once owned by the Aylesbury canal

carrier, A. Harvey-Taylor.