|

CONTENTS

DAME

ADELINE GENÉE, PRIMA BALLERINA

A KING OF

FRANCE IN TRING

A LETTER FROM

FANNY SMITH

MILITARY HOSPITALS IN TRING

during in the

Great War, 1914-1919

THE TRING AND

AYLESBURY TRAMWAY

THE WIRELESS − PRO.

AND CON.

ELECTRIC LIGHTING

A TALK ON TITHE

REMINISCENCES OF TRING

CHURCH

SEVENTY-FOUR YEARS AGO

A NOTE ON THE MUSIC IN

TRING CHURCH

TALK OF THE TOWN — IN

1701

SOCIALLE SECURITIE IN

MERRIE ENGLANDE

REGISTER EXTRACTS —1735

THE EXECUTION OF THOMAS

COLLEY — 1751

THE EXECUTION OF

EDWARD CORBET — 1773

THE TRIAL AND EXECUTION OF JOHN TAWELL ― 1845

BYGONE DAYS IN TRING:

1793

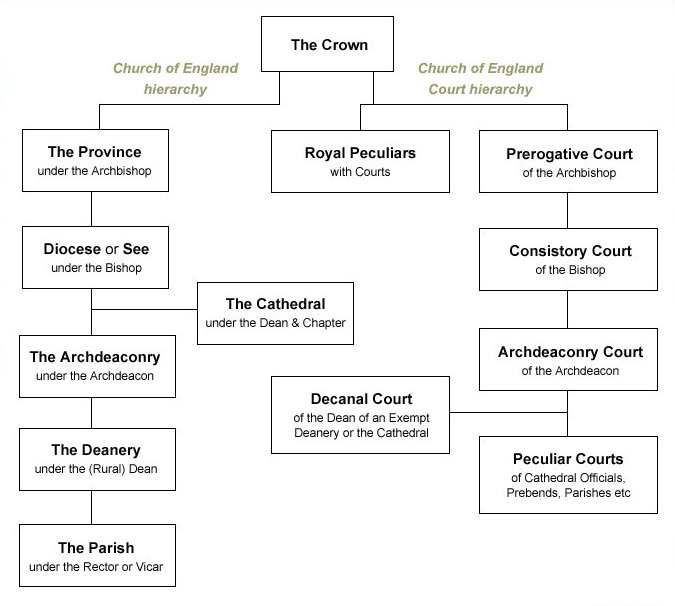

THE ARCHDEACONS’ COURTS

THE LOSS OF CHURCH

RAILINGS:

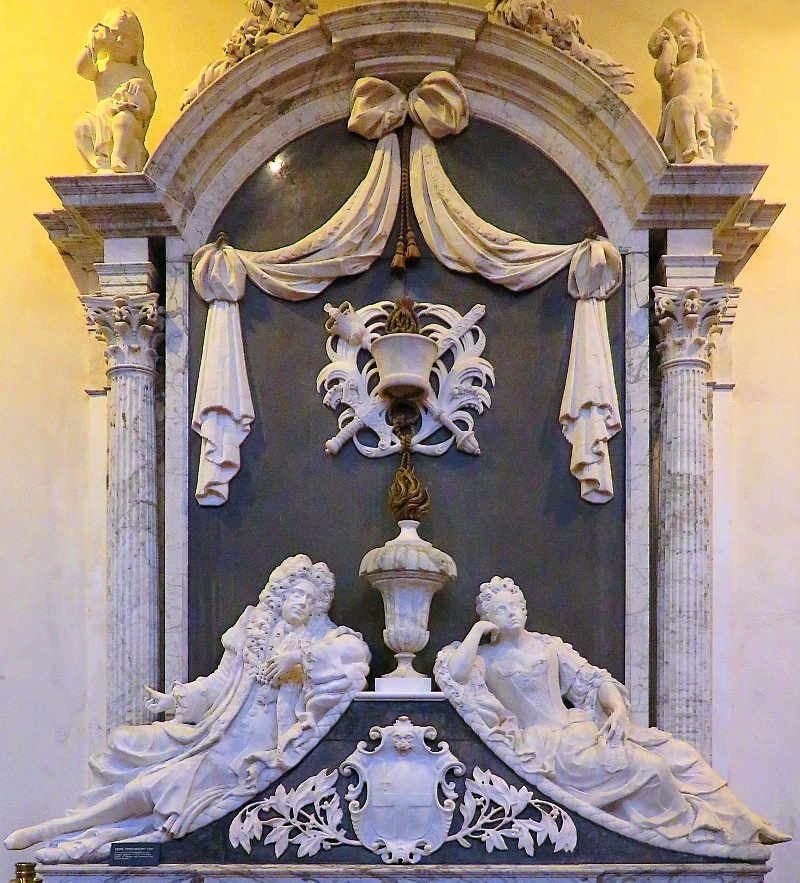

THE GORE MONUMENT

THE NAME OF TRING

DEATH OF MR. A. W.

VAISEY

TRING ’S

‘OTHER’ CHURCH

THE NORTH-WEST FRONTIER

GRAVELLY

FURLONG

SURRY PLACE IN

1912

JOSEPH CAN HEAR THE VOICES OF

TIME

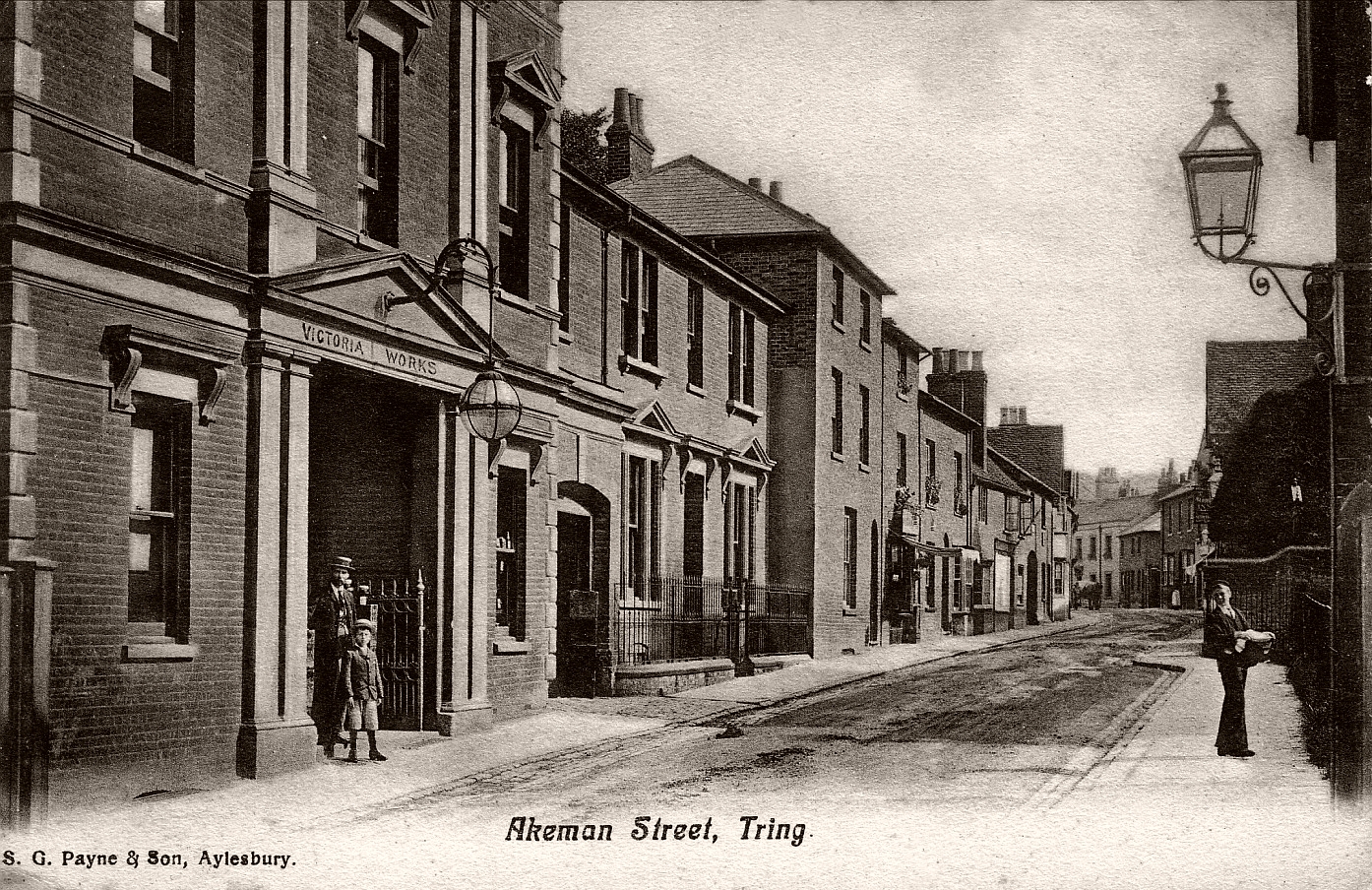

THE VICTORIA WORKS, AKEMAN

STREET

THE OTHER ALBERT HALL

――――♦――――

DAME ADELINE GENÉE, PRIMA

BALLERINA

Wendy Austin profiles a top Edwardian ballet dancer

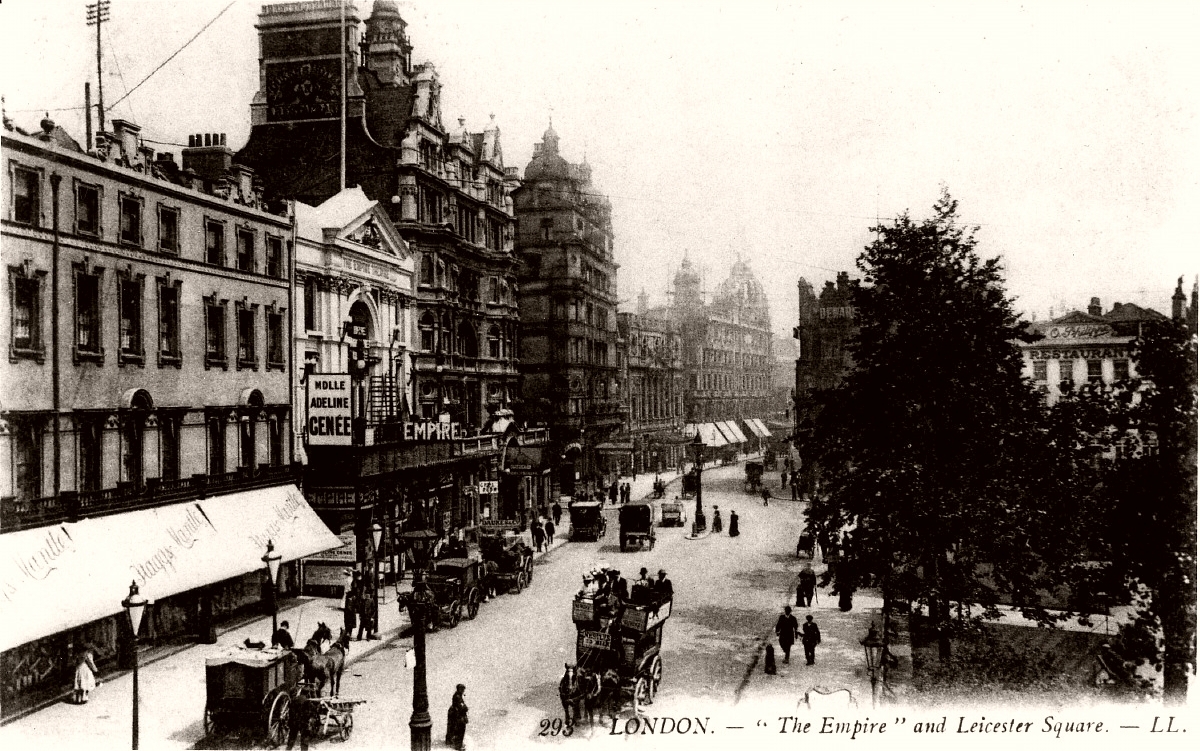

‘Fame is fleeting’. This well-worn phrase is shown as so true

when we look at the old postcard of the Empire Theatre, Leicester

Square, and the name highlighted on the frontage of that very centre

of London entertainment. Adeline Genée was at that time the

toast of Edwardian Theatreland, both in the capital and throughout

all the large towns of the provinces, but to-day, except among

ballet enthusiasts, she is almost unknown.

Adeline Genée:

premier of ‘La Camargo’ at the London Coliseum, 20th June 1912.

Genée was one of the very first of that new class of glamorous

artistes responsible for creating an interest in Ballet Dancing, an

art-form greatly appreciated on the continent but at that time

largely neglected in Britain. Although born in Denmark, Genée,

through her flawless technique and natural grace, became an English

institution in the years before the Great War.

All who saw her were immediately captivated by the artistry of her

work. Coming so closely after the burlesque, rough and ready

ladies operating on the boards at that time, Genée must have been a

revelation. It is interesting to note that the press comments

of the time used the same phrase constantly — “Her technical

perfection and sparkling invention” — it seems to say it all.

|

|

May

Cherry c. 1916: Adeline’s maid and dresser. |

My interest in Adeline Genée stems from the fact that for some years

my grandmother, May (née) Cherry, was her lady’s maid and dresser,

and she accompanied Adeline on her 1913 world tour. On my

grandmother’s death I acquired her collection of Genée mementos and

this caused me to want to learn more about her. I decided my

forays to Postcard Fairs would be a perfect place to search for

pictures of Genée, and I was not disappointed. These I found

had been published in great variety, and they open up a new window

on the whole period of the Edwardian theatre.

Genée was born in 1878 near Aarhus, Denmark, where her uncle,

Alexander Genée, owned an Academy of Dance. He quickly

recognised her outstanding talent, and in fact remained her ballet

master and impresario throughout her career. She made her

debut at the age of ten, and her first really big success came at

the Berlin Opera House in ‘The Rose of Schiras’ by Eilenbourg.

From there Genée progressed to Munich, London, then back to

Copenhagen in 1902 to dance before the King and Queen in ‘Coppelia’

in the part of Swanhilda — a role she subsequently made her own.

|

Mrs

May Gladys Vince, née Cherry, originally lived in

Williams Place, Tring, later demolished to make way

for Louisa Cottages. She left Adeline’s

service as maid and dresser when the ballerina

retired at the outbreak of the Great War, and

returned to Tring where she married. |

The Empire,

Leicester Square, c.1905. Genée’s name is displayed on the

billboard.

Adeline

danced here as prima ballerina from 1897 to 1907.

She first came to England in 1897 to fulfil a six weeks’ engagement

at The Empire Theatre, Leicester Square. What was intended as

a short period stretched to ten years, as her contract was

constantly renewed and new ballets were created for her. In

this time she achieved enormous popularity for her superb dancing

and expressive mime.

Adeline Genée in

‘The Dancing Doll’, Empire Theatre London, 1905.

The training and environment of Danish Ballet at that time was quite

as skilled as that of the Russian Ballet companies, and this seems

confirmed by the fact that Sergei Diaghilev, who was touring Europe

with his hugely successful Ballet Russe, at once recognised Genée’s

genius, and coveting her for his company, invited her to join him.

Genée, however, declined, and later privately described his

organisation as ‘a circus’, which was intended to glorify an

individual dancer, Nijinsky, rather than the art-form itself.

Like Pavlova ten years’ later, Genée was content to dance with her

own smaller and carefully-chosen company. Her artistry gave

pleasure to countless people — including officers of the ‘Titanic’

who sent a bouquet of red and white (the Danish colours) roses to

her dressing room on the night of embarkation on what was to prove

the fateful voyage.

She was toasted in song and poetry, and I quote one verse from a

poem ‘Lines to Adeline Genée’ published in 1913 (one verse is

enough! The florid Edwardian style is hardly to our taste today):

‘No sylph or faun of fabled dance,

No columbine or sprite,

Had half the power to lure and trance,

You Daughter of Delight.’ |

Genée’s long association with The Empire Theatre ensured her a place

as guest of honour at the final performance (a production of George

& Ira Gershwin’s ‘Lady, Be Good’), before it was demolished to be

rebuilt as a cinema in 1927. The star of that show, Fred

Astaire, in his curtain speech acknowledged her as the early

inspiration of his own career. When younger, he and his sister

were taken by their mother to a Ziegfeld production of ‘The Soul

Kiss’ in New York, which starred Adeline Genée. He tells that

they were brought by their mother night after night in the hope that

some of the artistry would rub off on them. Obviously in this

she succeeded.

Genée in fact toured the United States six times, the first being in

1908. As in Britain, her dancing was revelation to American

audiences and she received a rapturous reception wherever she

appeared. In 1913 she took her own company to Australia and

New Zealand, the first dancer to bring the classical style to those

countries.

Genée enjoyed many triumphant seasons at London’s ‘Coliseum’, where

she presented ‘La Danse’, an authentic record of Dancing and Dancers

from 1710 to 1845. She recreated roles made famous by great

dancers of the past, including Camargo, Taglioni and Provost.

Contemporary accounts of her appearance constantly refer to Genée as

“doll-like”, “elfin”, “light as thistledown”.

Adeline c. 1916.

All this was not, however, maintained without an effort of will.

Genée was a rigid teetotaller who dined frugally at three in the

afternoon, and allowed herself only a cup of coffee at six.

After that nothing until beyond midnight. She practised for at

least five hours every day in a room walled with mirrors, so that

she could see every movement, and how it appeared to the onlooker.

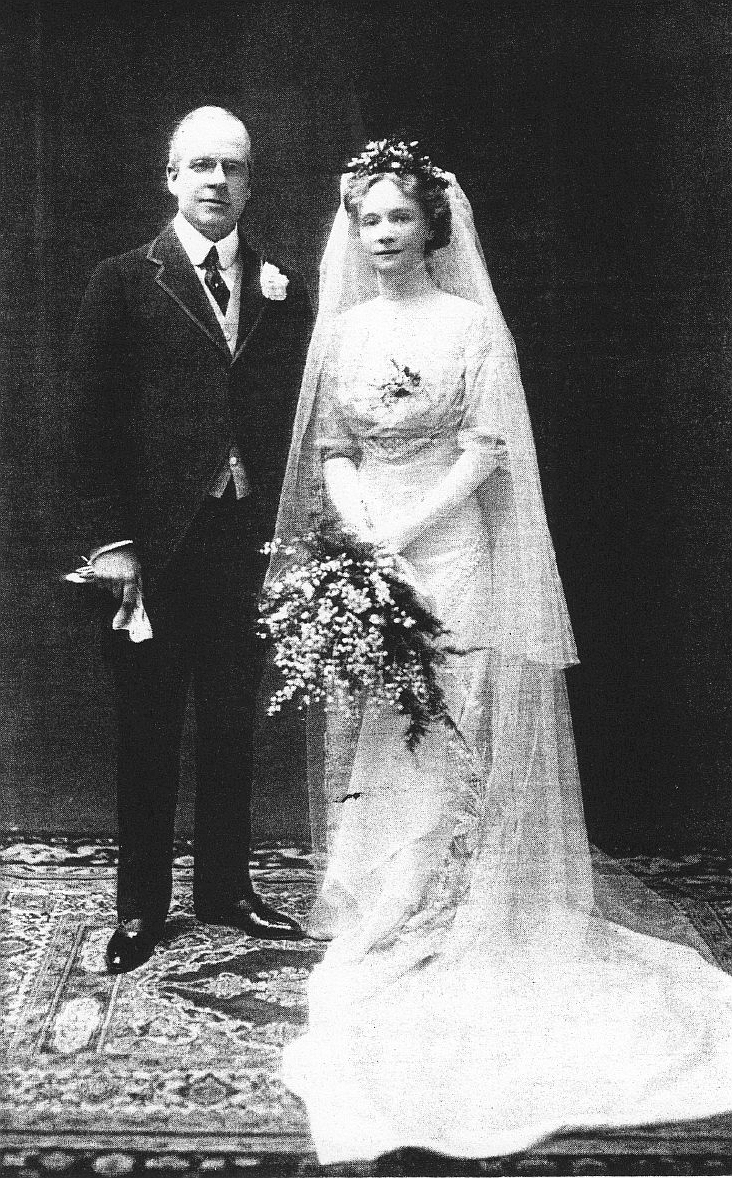

Genée did not make the mistake of carrying on too long, and at the

height of her fame and popularity she retired from the stage. In

1910 she had married a wealthy English lawyer, Frank S. N. Isitt,

and at the time of her marriage had promised him she would dance for

only a few more seasons. She kept her promise, retiring in May 1914.

However, the outbreak of war brought fresh demands for her to

continue, as it was thought her great popularity would be a, morale

booster to both servicemen and the general public.

Adeline Genée and

Frank S. N. Isitt on their wedding day in 1910.

“Don’t remember me only as a dancer” she once said. Only a

third of her long life was devoted to appearing on the stage.

In retirement, she worked hard to help create the Royal Academy of

Dancing in this country, and as the first President she travelled

widely, adjudicating, teaching and helping to select good teachers

throughout the country.

Even in retirement, Genée continued to receive honours. She

was appointed a Dame of the British Empire in 1950, and in 1967 a

theatre named after her was opened in East Grinstead. Also in

that year a yellow cluster rose bred by Harkness was named after

her. She died at the great age of 92, having admitted that she

had been lucky in never having had to fight her way to stardom.

I’m sure she would have been pleased to know that at least one

person is keeping her memory alive by collecting postcards of the

time, which depict her in the graceful poses for which she was so

famous, and in beautiful costumes (which my grandmother so proudly

helped to sew and care for). If any postcard dealers read this

article, perhaps in future when I ask “Adeline Genée, please?” I

will be met with recognition of the name. So far I usually

have to add “She was a dancer, but you may have her filed under

Actresses.”

Wendy Austin

November 1994.

――――♦――――

A KING OF FRANCE IN TRING

by Wendy Austin

Louis XVIII of France by Antoine-Jean Gros.

Seldom has a king found reason to pass through Tring publicly, let

alone a foreign king, so when it happened it made a newsworthy item.

Thus, on 20th April 1814 the Clerk to Tring Vestry recorded the

following:

“Louis XVIII, with his

retinue, passed through Tring on his return to France to take

possession of the throne. A detachment of Bucks Yeomanry with

trumpeters, formed the escort. Aylesbury gave him a great send

off, but there was no demonstration in Tring, although a great

number of people lined the street. During the King’s residence

at Hartwell House, the British Government have allowed him £20,000

per annum.”

Hartwell House, a Jacobean mansion, lies just west of Aylesbury, and

it might be that the town accorded Louis a great send off as either

many were relieved that his departure would mean a large saving to

the British public purse, or that the businessmen of the area would

genuinely miss Louis, due to the revenue brought in by the spending

of his courtiers, numbering over one hundred. Our Prince

Regent, the future George IV, had been generous to a fellow monarch

in trouble, granting him indefinite asylum in England, and Sir

George Lee, owner of Hartwell, had no doubt welcomed the kudos and

income (£500 p.a.) afforded by renting his house to an exiled king.

Hartwell House.

Louis had been fortunate, fleeing France in 1791 and thus escaping

the fate of his beheaded brother, Louis XVI, and many of his

relations. After some years spent in the Low Countries and

Sweden, he arrived at Hartwell in 1807: it must have been rather a

squash for such a large retinue, and life in rural Buckinghamshire

not doubt proved unexciting for one accustomed to the splendours and

intrigues of court life at Versailles. The story goes that he

took to his coach as frequently as possible to rumble his way to

London along the Sparrows Herne turnpike road to seek the

entertainments that the capital provided. Tring’s Vestry

minutes inform us that he passed through the town many times during

those years, but there is no record that he stopped at the Rose &

Crown. Louis’s first port of call was the main coaching inn at

Berkhamsted where he tarried a while, having become a close friend

of the comely daughter of the landlord of the King’s Arms. (It

should be mentioned that his wife, Marie Josephine of Savoy, had

died in 1810, and again the helpful Vestry minutes record that the

cortège passed through Tring on its way to Westminster Abbey.)

Following the fall of Napoleon, restoration of the French monarchy

came in 1814 when Louis returned to Paris to be greeted with a

boisterous reception. His subsequent ten-year reign was not

especially successful, although he did attempt to heal the wounds

caused by the Revolution. Queen Victoria’s mentor, her uncle

Leopold of the Belgians, admittedly always subjective, was no

admirer of Louis and in a letter to his niece wrote “Louis XVIII was

a clever, hard-hearted man, shackled by no principle, very proud and

false.”

By the spring of 1824 Louis was suffering from obesity, gout and

gangrene in his legs and spine. He died on 16th September 1824

surrounded by the extended Royal Family and some government

officials, in the process achieving the distinction of being the

last French monarch to die while on the throne.

――――♦――――

A LETTER FROM FANNY SMITH

with thanks to Mike

Hutchinson, Tring Park Archivist

The first Smith to live at Tring Park Mansion was Sir Drummond

Smith, the first Baronet of Tring Park and the only holder of the

title ever to live there (from 1786 to 1816) [Note].

It is unclear how Sir Drummond made his money - some was probably

inherited - but he was wealthy and was looking for a country estate

to move to from his existing home in Newmarket (Chippenham House).

When Sir Drummond died without issue in 1816, the estate was sold by

his executers to William Kay, a Manchester textile magnate who later

built and operated Tring’s well-known

silk

mill. But Kay never lived in the Mansion preferring

instead his London address at York Terrace, Regent’s Park, and over

the years he and his family rented the Park to a variety of tenants

until eventually it was bought by

Rothschilds in 1872.

One of the Mansion’s first tenants were Sir Drummond Smith’s niece

Augusta and her children. The letter below, written by Frances

(Fanny), one of Augusta’s daughters, gives an interesting insight

into the life of a well-to-do family in Tring in the 1820’s:

2nd October 1828 — We

continue to like Tring exceedingly and I do hope nothing will occur

to make us leave it. I like every thing about it, house, park,

country and neighbourhood; the latter, tho’ not numerous here, have

been very civil to us and among them there are some very nice

people. The poor here are very numerous and in a wretched

state, and Sunday School is constantly increasing; Eliza and I teach

the boys, the others manage the girls. The silk mill and straw

plaiting do not, I am sorry to say, tend towards improving their

morals or manners.

Our clergyman here is a very pleasant man and has a wonderful talent

both for music and painting, it is delightful to have him play upon

the pianoforte, and if he did but happen to be married we might see

him oftener then we can venture to do now in this evil speaking

world.

Our landlord Mr. Kay has treated us with rather more visits than we

wish for. He is offensively civil, but there is an easy

vulgarity in his manner, which is almost intolerable, and yet we

want to keep on good terms with him to remain here.

We had a very agreeable visit from the Protheroes who are very nice

people indeed, and very civil to us. Their son was an old

friend of ours and introduced us to his father and mother, they have

a most charming library; it is one that requires one to recollect

the 10th commandment not to wish for it, book and bindings. I

do not know what are the best.

Miss Gerinstons two of Lord Davulan’s sisters are some very

agreeable neighbours of ours, pleasing ladylike manners and people

of a certain air without being old maidish.

From this letter Fanny gives the impression that she is thoroughly

enjoying life at Tring Park. The silk mill and straw plaiting

industries of the area seem to give her cause for concern about the

morals of the young of Tring, who have no option but to work in

them. It is nice to see the sisters helping with the education

of the young of the town.

The town gossips of the time also play on her mind. Single man

visiting the young girls, even if he was a reverend was obviously a

no, no (Mr. Lacy did go on to marry a Miss Prickett, by all accounts

with a little help from Augusta). From Fanny’s description Mr.

Kay was not a well thought of gentleman. I imagine a

self-made man who didn’t worry a fig what the gentry thought of him.

All in all life seems to be rosy for Fanny and the Smith family.

Note: Augusta’s husband would have been the 2nd

Baronet of Tring Park but he died before Drummond. Following

Sir Drummond’s death the title passed to Augusta’s son Charles as

the 2nd Baronet; he married before Augusta moved into Tring Park and

never lived there. The title Baronet of Tring Park is extant,

the sixth and present baronet being Sir John Hamilton Spencer-Smith,

born 1947 (the heir presumptive to the baronetcy is Michael Philip

Hamilton-Spencer-Smith, born 1952).

――――♦――――

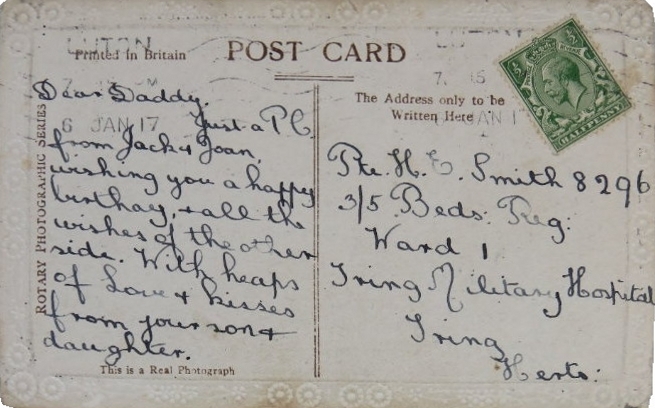

MILITARY HOSPITALS IN TRING

during in the

Great War, 1914-1919

by Ian Petticrew

THE NEED FOR TEMPORARY HOSPITALS

Following the commencement of hostilities many men too badly wounded

to make a recovery abroad were returned to Britain for medical

treatment. On arrival at British ports they were

assessed in Red Cross temporary hospitals before being dispersed to

military hospitals throughout the land.

Before the

outbreak of war the British Red Cross earmarked suitable buildings

for use as temporary hospitals. What they selected varied

widely, ranging from town halls and schools to large and small

private houses. The most suitable became “auxiliary general

hospitals”, which operated as annexes to central military hospitals.

Although under military control they were administered by the Red

Cross. Each could accommodate several hundred patients in the

bedridden

category, while convalescent and ambulant patients were sent

to smaller establishments. Some specialised units were also

set up, for example to treat shell-shocked and neurasthenic

patients; in this category Craiglockhart War Hospital near Edinburgh

dealt with shell-shocked officers, among them being the war poets

Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen.

Gadebridge

Military Hospital at Hemel Hempstead, a facility for 800 men,

specialised in treating soldiers with venereal disease (in 1918

there were 60,099 hospital admissions for VD in France and Flanders

alone. By contrast, only 74,711 cases of ‘Trench Foot’ were

treated by hospitals in France and Flanders during the entire war,

a total that also includes those suffering from Frost Bite.

While rarely fatal, on average VD cases required a month of

intensive hospital treatment).

These temporary hospitals and convalescent homes were to prove vital

for easing the pressure on the main military hospitals in treating

the rapidly increasing numbers of repatriated wounded servicemen

(well over 1 million in total).

Frodsham Auxiliary Military Hospital,

Cheshire.

During the period of the hostilities over 3,000 patients were

treated there.

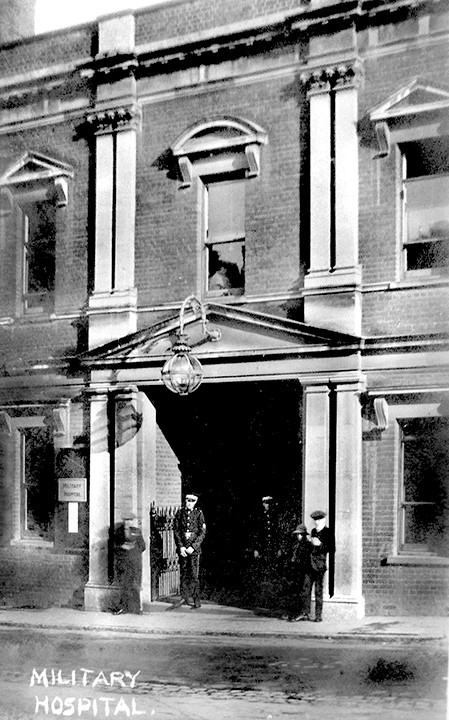

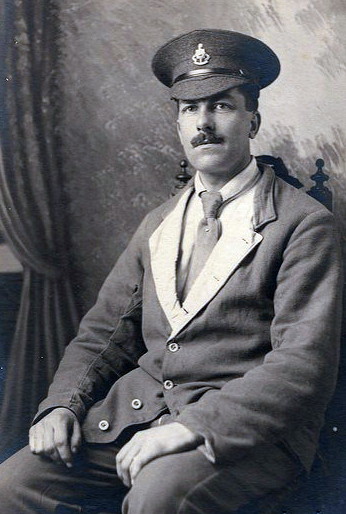

THE TRING MILITARY HOSPITAL

Where soldiers ended up depended largely on the

severity of their wounds. The patients at the smaller military

hospitals such as Tring did not, as a rule, have life-threatening

injuries but needed time to convalesce. That said, among his

recollections of Tring in past times, local historian Bob Grace

records that by 1915 Tring was receiving patients from the

disastrous Dardanelles Campaign.

During the war, at least three military hospitals –

probably physically separate elements of a single establishment –

are known to have existed at Tring. Very little information

about them survives; much of what there is appears in contemporary

editions of the Bucks Herald, in which the earliest reference

is to the Victoria Hall in Akeman Street:

“TO

THE EDITOR OF THE BUCKS HERALD:−DEAR SIR, In your last week’s

issue the following paragraph appeared − ‘A suggestion that the

Victoria Hall, Tring, should be equipped as a hospital for the

wounded is regarded in many quarters as somewhat premature.’ I

wish to state that it is the duty of Voluntary Aid Detachments who

work in connection with the British Red Cross Society to select

suitable buildings for temporary hospitals should they be required.

Guarantees are got from local residents for equipping these

hospitals, so that should the necessity arise they could be fitted

up at very short notice.

At present no hospital exists in Tring but should the War Office

require such, arrangements are being made by the local detachment

whereby a fully equipped hospital could be set up in a few days.

Yours truly,

WINNIFRED BOYSON,

Hon. Secretary and Commandant,

Tring Voluntary Aid Detachment.

Grove Lodge, Tring

August 20th, 1914.”

Bucks Herald, 22nd August 1914

This facility was set up initially to deal with the

large number of new recruits from the 21st

Division (part of Kitchener’s Third New Army, ‘K3’)

who were billeted in Tring while undergoing training, for this news

article refers to “illness” rather than “wounds”:

“The Victoria

Hall has been equipped as a hospital by the local Voluntary Aid

Detachment. It is furnished with six beds, and any cases of illness

amongst the recruits will be treated there.”

Bucks Herald 19th Sept. 1914

The Victoria Hall military hospital

(note sign to left of doorway).

Shortly after the military announced their intention

to extend their medical capacity in Tring:

“The military authorities are looking about for

further hospital accommodation, and in addition to utilising the

isolation hospitals of the district

[at Little Tring and Aldbury],

are contemplating taking over the High-street Schools.”

Bucks Herald, 17th Oct. 1914

. . . . and they

then moved quickly:

“Last week the military took over the High-street and

Gravelly

[at the top of

Henry Street]

Schools,

and they are now being fitted up for the

reception of cases of ordinary sickness occurring amongst the

troops. The authorities also expressed their desire to use the

Tring and Aldbury Hospitals for the reception of infectious diseases

amongst the soldiers . . . . The military patients at the

[isolation]

hospitals will be attended by Army Doctors, but beyond this the

administration of the hospitals (including the appointment of extra

nurses) will continue as at present . . . . The fee to be paid in

respect of military patients received into either hospital will be

27s. 6d. a week for each patient.”

Bucks Herald 24th Oct. 1914

Tring School (on the left).

It stood on the High Street site now occupied by the Library

and car park.

The schools’

pupils had then to be moved to temporary accommodation for the

duration:

THE

SCHOOLS:–

The children reassembled on Tuesday morning at their new quarters in

various parts of the town. All the town schools are now in the

hands of the military authorities, and are being prepared for

hospital purposes.

Buck Herald, 14th Nov. 1914

“The playgrounds at the High-street

Schools have been shut in by a high closely-boarded fence, which

makes it impossible for anyone to overlook the grounds from the

High-street. It is understood that the schools will be used as

a military hospital for the

[21st]

Division, and will take the place of the Victoria Hall, which is to

be vacated shortly.”

Bucks Herald, 19th Dec. 1914

This poor quality image is all that is

known to have survived from

Tring School’s

days as a military hospital. Note the hospital uniforms.

Meanwhile the military also commandeered Tring Market

House:

“It

was reported that the military authorities had applied for the use

of the Market House as a depot for hospital stores. The

Chairman, after consultation with the Chairman of the Market House

Committee, had granted the use of the building, and his action was

confirmed. It was left to the Market House Committee to fix a

charge to cover the cost of light and firing should these be

required.”

Bucks Herald, 17th Oct. 1914

Following the requisition of the schools their pupils

were moved to various locations in the Town. Boys went to the

Church House and Market House, girls to the Lecture Hall in the High

Street Free Church and to the Western Hall (now the site of Stanley

Gardens), while infants were sent to the Sunday School room in the

Akeman Street Baptist Chapel, while the YMCA building in Tabernacle

Yard (off Akeman Street) was opened as a writing and reading room

for soldiers, for whom bathing facilities were installed in the

Museum outbuildings. Although used for social purposes, it

seems that the Victoria Hall continued to serve as a medical

facility until at least 1916:

“On Wednesday evening a soldier of the Herts

Territorials, while cycling near Ivinghoe, came into collision with

a motor car. He was thrown from his machine, and his collar

bone dislocated. He was put into a car and driven to the

military hospital, Victoria Hall, Tring, where his injuries were

attended to, and he was afterwards moved to the military hospital at

Aylesbury.”

Bucks Herald, 27th May 1916

In 1916 a Zeppelin is believed to have passed over Tring on its way

to bomb London. The military hospital was made ready to

receive the expected casualties from an air raid on the town:

“ZEP

SCARE:–Soon after midnight on Saturday a warning to prepare for an

air raid came through. Specials and firemen were at once

called out, and at the military hospital preparations were made for

the reception of casualties. How near the Zeppelin came to

Tring is uncertain, but the light from the one that was set on fire

and which fell at Cuffley was distinctly visible in the town

illuminating a wide area, and the noise made by the engines was

plainly heard. It was 4.30 on Sunday morning before the danger

was reported over, and the tired specials and others were permitted

to return to their beds.”

Bucks Herald,

Sept. 9th 1916

ORGANISATION AND NURSING

No information exists on how the Tring Military

Hospital was organised, but the pattern followed was probably the

same as that applying to similar establishments elsewhere:–

-

a Commandant in charge of the hospital;

-

a Matron (or equivalent) who directed the nursing

staff;

-

a Quartermaster responsible for the receipt,

custody and issue of articles from the

provisions store;

-

members of the local Voluntary Aid Detachment

(VAD) who were trained in first aid and home nursing.

Local GPs sometimes helped, while women and those too old to work in

a main military hospital often volunteered for part-time work.

There were also some paid roles, such as cooks. The Bucks

Herald makes a couple of references to those who worked at

Tring:

“A VETERAN

HOSPITAL

ORDERLY:– ‘Bob’ Matthews, one of the best known and most esteemed of

the R.A.M.C.

[Royal Army

Medical Corps]

orderlies at the

Tring Military Hospital, has a record of service of which he may

well be proud, and it is creditable to him that he is still able and

willing to carry on such splendid work, although much of it may be

of a menial character. Residing at Maidenhead, he assisted in

the formation of the local Red Cross detachment, and was one of the

first to answer the call for volunteers at the beginning of the war.

He has to his credit some 30 years’

service in the Berks Volunteers, and held the Long Service Medal,

retiring with the rank of sergeant. Keenly interested in the

friendly society movement, his work for his local Court of Foresters

was of a most useful character, and his interest in sport made him a

keen supporter of the local football clubs, whilst with the patients

and staff at the hospital ‘Bob’ is most popular, and most energetic

in carrying out his duties.”

Bucks Herald, 19th May 1917

“THE

HOSPITAL:–

Much regret is felt at the removal of Captain A. Holland Wade, who

has been transferred to another military hospital in the eastern

Counties. During the ten months he has had charge of the Tring

Military Hospital, Captain Wade has made many friends in the town,

and his loss will be felt, especially in the organisation of

concerts, for several of which he has been responsible during the

spring and summer, greatly to the benefit of a number of deserving

war charities. Possessing a fine baritone voice, Captain Wade

was always a welcome addition to any programme, and made frequent

appearance at the Y.M.C.A. concerts. The good wishes of all go

with him to his new sphere of labour.”

Bucks Herald, 27th Oct. 1917

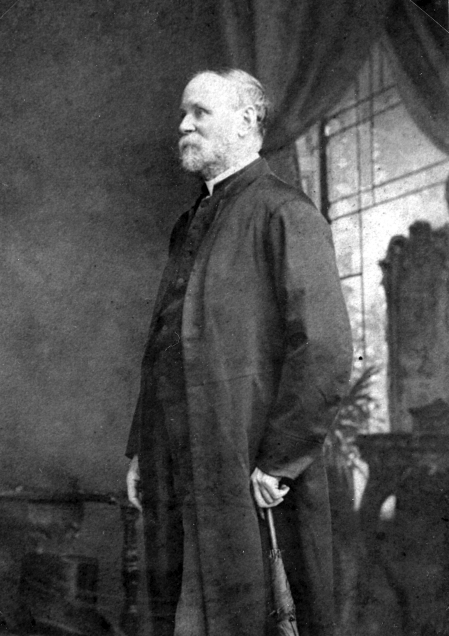

Among those undertaking pastoral duties was the Rev.

Charles Pearce, a local non-conformist clergyman. Later in the

war, in addition to his already considerable duties, the Rev. Pearce

received the distinction of being appointed Officiating Chaplain in

local military hospitals to the Wesleyans, Presbyterians,

Congregationalists, Primitive and United Methodists, and Baptists,

thus filling the unique position of representing all of the Free

Churches.

The Rev. Charles Pearce.

In 1915, Rev. Pearce wrote to the Editor of the

Bucks Herald

acknowledging the efforts of the medical staff at the three military

hospitals (presumably the High Street School, Gravelly School and

the Victoria Hall):

Fernlea, High Street, Tring.

10th November

1915.

Dear Sir,

Much, but not too much, has been

written about the officers and men of Halton Camp and at the Front.

I believe you will think a line or two about our Hospitals worthy a

place in your valuable paper. Neither rose nor rainbow gain

anything from painter or poet, and deeds of mercy require no

flourish of the pen. A simple statement will be enough to show

the skill, sympathy, and success of the doctors, their staff, and

assistants. We have had three Military Hospitals in Tring for

considerably over 12 months (a number of the wounded from the Front

are now here); but, as far as I remember, we have had only three

deaths. Surely this must form a record. Some of these

were very seriously ill before admittance. I have been deeply

touched by the tears in the tone: “We did our very best, but could

not save him”. The men seem to have undoubted confidence in

the medical staff and their helpers. The monotony of indoor

life is just now largely increased by the darkened windows.

But all are hopeful of brighter days.

Yours etc.,

Charles Pearce, Army Chaplain

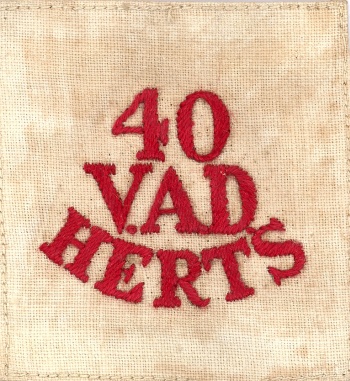

County branches of the Red Cross had their own groups of volunteers

called Voluntary Aid Detachments, whose members came to be known

simply as ‘VADs’. Made up of men and women who had to pass

exams to receive their first aid and home nursing certificates, the

VADs carried out a range of voluntary work including nursing and

transport duties:

“The military hospital at the Victoria Hall is in

charge of the R.A.M.C.,

who are working in conjunction with the Voluntary Aid Detachment . .

. . The result of the recent examination for first-aid certificates

was not satisfactory, only three men being successful. As the War

Office will only recognise a Voluntary Aid Detachment in which there

are at least twelve certified men, it is felt desirable that

opportunities should be afforded to enable others to qualify. A

second course of instruction will be arranged, should a sufficient

numb er of men signify their intention to join. There would be two

meetings a week – one for instruction and one for practice. The

Sergt-Major in charge of the R.A.M.C. Detachment at the Victoria

Hall has promised his help . . . .”

Buck Herald, 17th October 1914

Although the Buck Herald report placed an

emphasis on the need for men, by the summer of 1914, of the 74,000

VAD members, at least two-thirds were women.

Ada Jordan’s VAD

arm-band.

Ada Jordan (aged 17), daughter of Karl Jordan, a

Curator at Tring Museum, when serving as a V.A.D. found that some of

the soldiers in the hospital where she worked refused to be nursed

by her when they discovered that her father was German by birth,

even though a naturalised British citizen.

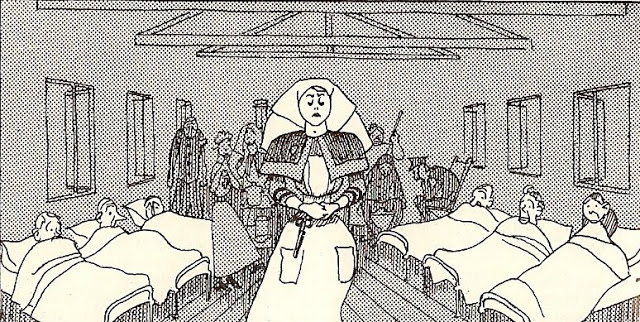

|

Cartoon of Wandsworth

Military Hospital.

Following the commencement of hostilities,

Fanny Girardet,

Tring’s

long-serving indefatigable district nurse, offered

her services to the Red Cross. She was posted to

the military hospital on Wandsworth Common. In

1916, her name appeared in the Birthday Honours List

when she was awarded the Royal Red Cross Medal, a

military decoration awarded in the United Kingdom and

Commonwealth for exceptional services in military

nursing. |

THE LITTLE TRING ISOLATION HOSPITAL

“The

[Town] Clerk reported

that Major Prynne, the principal medical officer of the 21st

Division, had called on him and explained that the Military

authorities desired to use the [Isolation] Hospital at Tring for

scarlet fever and diphtheria, and the Aldbury

[Isolation] Hospital for enteric

[typhoid]. At Aldbury they

were willing to allow use of the hospital for enteric on the same

terms as they charged patients from Tring, viz., 27s. a week; and

were prepared to erect tents or other accommodation if necessary.

Dr. Brown said that Major Prynne stated at Aldbury that the military

authorities did not wish their men to go into tents. In reply

to several Councillors, who pointed out the inconvenience of the

proposed arrangement, the Chairman said he was afraid they could not

help themselves. They would have to do whatever the military

authorities decided.”

Bucks Herald, 17th October 1914

This was an age in which serious infectious diseases such a

diphtheria, scarlet fever and smallpox were at large. Thus,

while continuing to serve the needs of the civilian population, the

Little Tring Isolation Hospital received patients from among the

soldiers billeted in Tring or based at the Halton military camp, and

temporary accommodation (military huts) was erected in the hospital

grounds to house them.

The military were given powers that permitted them to dictate how

the hospitals were to be used with regard to the civilian

population. Following a further meeting with the military the

Tring Urban District Council received a memorandum on the subject:

“The military

authorities desire to use the Tring Hospital for enteric fever

[typhoid], and the Aldbury Hospital for

scarlet fever and diphtheria, and this will necessitate the local

authorities [Tring and Berkhamstead]

using the hospitals in the same way. The only exception to

this will be that if one of the hospitals is standing empty the

military authorities will raise no objection to is being used

temporarily for any kind of infectious disease from its own

district, provided that reasonable accommodation is always kept

available at each hospital for the disease which the military

authorities have arranged should be dealt with there. The

cases at the two hospitals are to remain until discharged in the

ordinary way.”

Bucks Herald, 24th October

1914

A

later press report suggests that the military section of the

Isolation Hospital had its own commandant and did not form a part of

the Tring Military Hospital:

“CAPTAIN

SHAW,

R.A.M.C.:–Eulogistic reference was made in the House of Commons on

Tuesday to the services of this medical officer in the epidemic of

cerebro-spinal fever

[meningitis]

which has occurred among young naval officers at Cambridge. Captain

Shaw is in charge of the Isolation Hospital, Tring, where he has

done splendid work in combating this dread disease, and for the past

six weeks has been lent to the Admiralty for special service at

Cambridge.”

Bucks Herald, 22nd March 1919

Overcrowding appears to have been a problem at times:

“THE

HOSPITAL:–The

[Town] Clerk

reported that complaints had been made as to overcrowding at the

[Tring]

Isolation Hospital. Beds for 40 patients were provided, and 70

men had been taken in. He had written to the Military

Authorities, and told them that the Council could not accept

responsibility for any consequences of overcrowding,–The Matron

reported that 62 patients had been admitted: 22 with measles, 29

scarlet fever and 12 diphtheria cases. Fifty-three patients

had been discharged, and 3 died.”

Bucks Herald, 20th May 1916

The article does

not distinguish the split between military and civilian in the

statistics, but some deaths were reported in the press, such

as that of Private Arthur Baxter, son of Mr. H. E. Baxter, of

Walsoken, Wisbech, Cambs. Arthur is buried in Tring Cemetery

(grave ref. F18):

MILITARY FUNERAL:–A young private

of the Cambs. Territorials was buried with full military honours on

Monday afternoon. He died in the Tring Isolation Hospital, to which

he had been removed from Halton Camp, suffering with scarlet fever.

Bucks Herald, 10th June 1916

|

|

|

Private Heaton Bailey, R.A.M.C. |

Rather more is known about Private Heaton Bailey,

R.A.M.C., son of Mr. and Mrs. J. Bailey, Bolton Road, Silsden,

Yorkshire, who is reported to have died of pneumonia at Tring on the

6th March 1918, aged 19 years. On 25th August 1917 Private

Bailey was transferred to 1st Training Battalion, R.A.M.C. at

Blackpool. Between 14th November 1917 and 19th December 1917

he was admitted to the Military Hospital, Kirkham near Preston with

Influenza. On 10th January 1918 he was posted to No 9

Company at Colchester, then transferred to Aylesbury for

hospital training. After working for some time at the Military

Hospital, he acted as orderly in the isolation ward of a

neighbouring hospital. Whilst there, he contracted scarlet

fever, and after being removed to hospital in Tring (probably the

Isolation Hospital), he had another attack of pneumonia in addition

to the fever. His condition became worse, and his parents were

only able to reach the hospital shortly before he died, although he

was unconscious when they arrived (obituary in the Keighley Boys

Grammar School magazine, edition Nov. 1918).

It appears that the Forces Chaplain (Rev. Pearce)

held the Isolation Hospital’s

long-suffering Matron in high esteem, for he wrote to the Editor of

the Bucks Herald heaping his praise on her:

“We cannot but admire and feel grateful to the Matron

at our Isolation Hospital. She has done well under the most

trying circumstances. She came to a comparatively quiet

resting place, but since the military occupation, and all the new

[in fact temporary]

buildings, the work has been enough to tax the skill and strength of

the most devoted; her ability and love have enabled her to bear the

burden and discharge her duties so splendidly. We have nothing

but praise for all responsible for our hospitals in the town, and we

have never heard a complaint from one of the sufferers under their

charge, but many have expressed their surprise at the patience and

tenderness with which they have been treated.”

Bucks Herald, 3rd June 1916

At an Urban District Council meeting in February

1917, the Matron reported:

“17 patients admitted during the month; 4 discharged;

17 remaining in the hospital. She applied for an honorarium

for extra work since the Hospital had been used for the military.

From 1914 to the beginning of 1917, 266 military patients had been

admitted, and much extra work thereby entailed.”

Bucks Herald, 17th Feb. 1917

Both the

Matron and her nurse later received their honorarium, but in

reporting this the Editor of the Bucks Herald failed (discreetly)

to disclose the amount.

ENTERTAINMENT AND LEISURE

As for the relaxation of patients during their recuperation, there

are numerous reports in the local press of visits and of concerts

organised in the town, often by the military and with a military

input to the entertainment. For example:

“GIFTS

TO SICK SOLDIERS.–On Christmas afternoon Councillors the Rev. C.

Pearce and Messrs. R. W. Allison. Bentley Asquith, and T. H. Hedges

visited the two military hospitals and distributed cigarettes to the

inmates, and also gave the nurses boxes of chocolates. These

gifts had been subscribed for by the townspeople as a Christmas gift

for the strangers within the gate. The recipients were

surprised and delighted with the present, and the generous and

kindly feeling which prompted it, and several grateful letters of

acknowledgment have been received. About 15,000 cigarettes

were distributed, and these, as well as the chocolates, were all

obtained through local tradesmen.”

Bucks Herald,

2nd Jan. 1915

“GRAND

ENTERTAINMENT:–

In aid of the Officer Prisoners of War Fund, an excellent programme

was submitted at the Victoria Hall on Wednesday evening. The

arrangements were in the capable hands of Lieut. A. Holland Wade,

R.A.M.C., medical officer at the local Military Hospital, and it is

not too much to say that in every detail they were perfect, and the

concert in every way a complete success . . . . Lieut. Holland Wade,

whose vocal powers are well known to local audiences, made two

appearances, and was deservedly encored.”

Bucks Herald, 28th April 1917

Added to the entertainments at the Victoria Hall were

occasional outings (note the American contingent):

“HOSPITAL

PATIENTS:–

The patients at the hospital enjoyed a pleasant drive on Wednesday

to Berkhamsted, returning via Ashridge and Aldbury. The men

are grateful to Lady Rothschild for her kindness in making possible

such enjoyable outings. Amongst the party were several

American soldiers, who were much impressed by the beauties of the

surrounding country.”

Bucks Herald, 20th Oct 1917

“HOSPITAL

PATIENTS:–

On Wednesday afternoon the patients at the local military hospitals

had a most pleasant drive in brakes to Aylesbury and home via

Wendover and the Camps. They were accompanied by the Rev.

Charles Pearce, O.C.”

Bucks Herald, 1st June 1918

|

|

|

A soldier

wearing hospital blues. |

During the period that the soldiers of the 21st

Division were billeted in Tring, William Mead, wealthy owner of the

Tring Flour Mill, fitted an annexe to the mill containing two

enormous baths for their use. He also invited wounded soldiers

for drives around the countryside in his steam lorry, finishing with

refreshments and games at the mill; those too ill to attend he

visited in the various local military hospitals.

“HOSPITAL PATIENTS ENTERTAINED:−Through the

kindness of Mr. W. N. Mead, the patients and staff of the Military

Hospital spent a happy time at Gamnel Wharf on Wednesday afternoon.

They were met on arrival by Mr. and Mrs. Mead, who has made every

arrangement for the pleasure of the men. Not the least

interesting item was a tour through the extensive flour mills, where

the work of many machines aroused great interest, which was enhanced

by the explicit explanation of the process by Mr. Mead. A

feature of the outing was a trip on the canal in a decorated barge,

the voyage to the Cow Roast and back, under the direction of Mr.

Mead as skipper, being most enjoyable. Bowls and other games

were provided in the delightful gardens and grounds, in which the

men and the staff took part.”

Bucks Herald,

14th July 1917

The photographs below are an example of the hospitality and

entertainment arranged by William Mead for wounded servicemen.

The soldiers embarking in the bow of one of Mead’s

barges (the Victoria) for a leisure trip on the Grand

Junction Canal are wearing

“hospital blues.”

This form of uniform was intended to ensure that convalescing

soldiers had a uniform they could wear in public, thereby avoiding

the risk of attracting white feathers from zealous armchair patriots

and accusations that they were not doing their bit for King and

Country.

|

|

|

.jpg)

.JPG)

.jpg)

A band of military musicians are seated

under the tarpaulin.

|

THE RETURN OF PEACE

When peace returned, the town gradually regained something

approaching normality, given that the Spanish influenza pandemic and

the coal and rail strikes had first to be endured. In those of

Tring’s buildings that had formed the military hospital, medical

supplies were packed up and sent back to Government stores.

During 1919, children returned to their pre-war

schoolrooms having spent four and a half years in unsuitable and

sometimes cold makeshift conditions. Collections were made in

the cinema (The Empire, Akeman Street) for the King’s Fund for the

Disabled, and books for the wounded were gathered and sent to the

Library Branch of the British Red Cross. A Victory Ball had

been held at the Victoria Hall, the

Bucks Herald reporting that the Hall was “profusely

decorated”; nearly 200 attended, most wearing fancy dress or

uniform, proceeds from the event being donated to the Local Hospital

Supply Depot.

――――♦――――

THE TRING AND AYLESBURY TRAMWAY

that might have been.

by Ian Petticrew

The opening of the Birkenhead Street

Railway Company, 30th August 1860.

George Train is pictured on the top deck with arm outstretched.

The street tramway arrived in Britain in 1860 when American

entrepreneur George Train opened a short line at Birkenhead.

Although his trams proved popular with their passengers, the tramway

suffered the drawback of using rails that protruded above the road

surface, thereby obstructing other road users. These were

later replaced with grooved rails and before

long most of Britain’s cities and towns of any size had trams, which

not only gave passengers a more comfortable ride than horse buses,

but the low rolling resistance of metal wheels on steel rails

allowed a greater load to be hauled for a given effort.

As for Train’s line, it eventually grew into a fairly extensive

street tramway system run by Birkenhead Corporation, which survived

until motor buses eventually took over in 1937.

Grooved tramlines.

Motive power was at first provided by horses, but in the age of

steam it was not long before attempts were made to replace teams of

horses with small steam locomotives, or ‘tram engines’. But

due to their restricted size, steam tram engines were usually

underpowered added to which their heavy maintenance requirement –

lighting the fire, removing ash and soot, periodically replenishing

water and coke (coke because they had to be smoke-free) and

lubricating – added to operational expense. One commentator

writing in 1889 gave the passenger’s perspective: “passengers

are choked with sulphurous vapour and buried in smuts if they

attempt a long journey on a steam-tram.” It is therefore

unsurprising that when electric traction became feasible in

the 1890s (the current being distributed by overhead cables), the

steam tram engine quickly faded from the scene.

However, one steam system did survive and in this area. Opened

in 1887, the 2½-mile Wolverton and Stony Stratford Tramway

brought workers from outlying districts into the London & North

Western Railway’s large carriage works at Wolverton. This

steam tramway ran until 1926, by which time it had earned the dual

distinctions of having the largest trailer cars to run in Britain

(seating 100 passengers) and being our last steam-worked street

tramway.

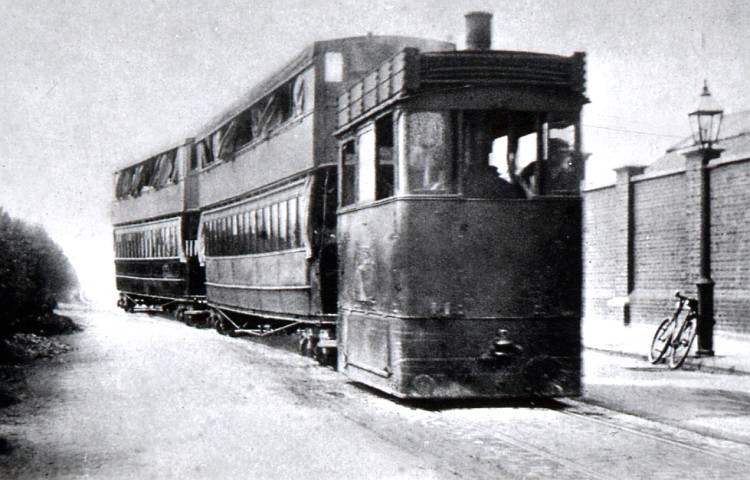

A Wolverton steam tram and trailers.

THE TRING AND AYLESBURY TRAMWAY PLAN: in 1887, reports and

notices appeared in the local press of a plan to build a tramway

linking Tring Station, via the town, with Aylesbury; the notices do

not mention whether that system was to be steam or horse powered,

but taking account of the length of the line and its gradients,

steam seems more likely. At the same time a grander scheme was

announced for a steam tramway linking Hemel Hempstead,

Boxmoor, Chesham, Berkhamstead and Northchurch:

A NEW TRAMWAY. ― A tramway is contemplated from Aldbury and

Tring in the county of Hertford: and Drayton Beauchamp, Buckland,

Aston Clinton, Weston Turville, and Aylesbury, in the county of

Buckingham. A system is also contemplated to connect the towns of

Berkhamstead, Northchurch, Chesham, Hemel Hempstead, and Boxmoor.

Bucks Herald, 22nd November 1887.

Descriptions of the route and its gradients survive in the

Hertfordshire Archive, which show that detailed surveying must have

been carried out before the announcements were made. To

protect the road surface, where practicable the trams were to run on

waste land at the side of the road. The tramway was to

commence opposite the goods entrance to Tring Station, cross the

Grand Junction Canal over the existing bridge and proceed up Station

Road (gradient 1:65) to Tring Lodge, after which there would then be

a short descent (1:20) to Brook Street. The line would climb

steeply at Frogmore Street (1:18) followed by a gradual ascent to

the summit of Tring Hill (1:48) before descending (1:20) to the Vale

of Aylesbury after which the route to the Aylesbury terminus was to

be comparatively level (1:100).

|

Miles |

Halting places |

Miles |

Halting places |

|

0 |

Tring Station |

4.63 |

White Lion PH |

|

1.25 |

Beechgrove House |

5.13 |

Rose & Crown PH |

|

1.50 |

Brook St. |

5.75 |

Vatche Farm |

|

1.75 |

Frogmore St. |

6.13 |

Aston Clinton Village |

|

2.25 |

Britannia Inn |

6.75 |

Broughton Farm |

|

3.38 |

Tring Hall |

7.50 |

Broughton House |

|

3.75 |

Gasworks |

8.25 |

Condensed Milk Works |

|

4.38 |

The

Junipers |

8.50 |

Park St. |

The press reports do not mention to what extent the scheme was

supported by the general public, but there were objectors:

THE TRAMWAY SCHEME. ― A Tring correspondent writes: We

understand that Lord Rothschild, Mr. Williams, and other owners of

property in the narrow part of the High-street have objected on

public grounds to the laying of the Tramway there. Even with

the present traffic the street is narrow and insufficient, and

accidents, especially on market days, are not infrequent. The

promoters will, it is thought, abandon the scheme, without incurring

the expense which opposition at a later stage of the order would

entail upon them.

Bucks Herald, 17th November 1887.

When the Tring Local Board (predecessor of the Tring Urban District

Council) met to discuss the scheme, their main concern was that part

of the High Street was too narrow to meet statutory

requirements:

LOCAL BOARD.― At the meeting of this Board on Thursday there

were present Mr. Butcher (chairman), Dr. Pope, and Messrs. Smith,

Chappell, Humphrey, Grange, Crouch, and Elliman; The Clerk (Mr. A.

W. Vaisey), and the Inspector (Mr. Baines).― The Clerk read a letter

from Mr. Battams, the solicitor to the Promoters of the proposed

tramway between Tring and Aylesbury, with reference to the posting

of the notices; and he also laid on the table the plans and sections

of the proposed line.

A discussion followed on the Board’s position on the matter.

The Clerk read several sections of the Tramways’ Act, 1870, which

referred to the position of the Board with regard to the persons

interested in that portion of the High-street which was too narrow

to allow the required width on each side of the rails.― Mr. Elliman

thought they should not forget that the tramways would give

facilities for getting about, and that they were generally

advantageous to a town. It might be the wish of the

townspeople to have the tramway.― After some discussion, the Clerks

was directed to issue a circular, drawing the attention of the

inhabitants to section 9 of the Act of 1870, which provides for the

case in which the street is too narrow to admit a width of “9 feet 6

inches between the outside of the footpath on either side of the

roadway and the nearest rail of the tramway.”

Bucks Herald, 3rd December 1887.

The Tring and Aylesbury Tramway scheme was finally laid to rest when

its promoters met with Lord Rothschild – Lord of the Manor of Tring

and a substantial and wealthy landowner in the town – whose main

objection to the tramway was that it would not be a financial

success. If true, how this would affect anyone other than the

scheme’s promoters and shareholders is unclear, for they would

probably have been required to arrange a bond to cover the cost of

road clearance should the scheme fail. The following newspaper

report refers to

“other objections”, which presumably included the narrowness of

the High Street (folklore has it that he also objected to trams

running past his residence):

THE PROPOSED TRAMWAYS SCHEME.―

It is stated that Mr. Wilkinson, the promoter of these schemes,

accompanied by the solicitor and the engineer, had an interview with

Lord Rothschild, Messrs. Leopold and Alfred de Rothschild being also

present, at New Court, St. Swithin’s-lane, on Wednesday, as to the

proposed line from Tring to Aylesbury, and that his Lordship having

intimated that the line would not received his support because,

among other objections to the scheme, he considered it was a line

which would not be a financial success, it was decided to abandon

the project. But as his Lordship at the same time intimated

that he felt certain that the line from Chesham to Hempstead would

be supplying a long-felt want to the district, and also prove a

certain commercial success, it has been decided to press forward the

project with the upmost vigour.

Bucks Herald, 24th December 1887.

What is surprising is that the tramway promoters appear not to have

foreseen such predictable obstacles before incurring surveying,

planning, legal and parliamentary costs. To modern eyes it

might also appear surprising that the word of Lord Rothschild should

carry such weight in the matter, but this was an age when the

peerage had considerably more influence than today, as was evidenced

when Robert Stephenson brought the London & Birmingham Railway Bill

to Parliament in 1832, only to have it thrown out – at great

cost to the Company – by Lord Brownlow of Ashridge and a coterie of

peers who objected to railways in general.

As for the Hemel Hempstead steam tramway scheme, it too sank without

trace. Newspaper reports of the time suggest that although it

met with widespread approval among the general public, there were

influential objectors among whom was Sir A. P. Paston-Cooper,

a land owner in the Hemel area (whose ancestor’s objections had

caused the London & Birmingham Railway to be diverted from the Gade

into the Bulbourne Valley). The press reports that Cooper “thought

the tramway horrid. People in London liked to come into the

country to enjoy the peace and quiet there, but would they come if a

beastly tramway were introduced?”

On the 11th August, 1888, a short notice appeared in the Bucks

Herald to the effect that the Hemel Steam Tramways Bill had

received the Royal assent, thereby becoming an Act of Parliament.

But despite having overcome all the legal obstacles to its

construction nothing further is heard of the scheme, which was

probably abandoned owing to lack of finance.

THE STATUTORY NOTICE

Bucks Herald, 26th November 1887.

BOARD OF TRADE ― SESSION

1888.

TRING AND AYLESBURY TRAMWAYS

―――――――――

(Construction of Tramways; Gauge; Motive Power; Tolls; Agreement

with Local and Road Authorities; Amendment of Act.)

―――――――――

NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN,

That application is intended to be made to the Board of Trade in the

ensuing Session for a Provisional Order under the Tramways Act,

1870, for the purpose or some of the purposes following, that is to

say:

To authorise a company to be incorporated in accordance with the

rules and regulations of the Board of Trade, or any other Company or

Corporation, Person or Persons, to be named in the Draft Provisional

Order (hereinafter called the Promoters), to construct and maintain

the following Tramways or some part or parts thereof, that is to

say:

Tramway No. 1, commencing in the parish of Aldbury, in the County of

Hertford, at a point opposite the Goods Entrance of the Tring

Station of the London and North-Western railway, thence passing in a

south-westerly direction over the Grand Junction Canal, and thence

along the road leading to Tring and along the High Street, Tring,

passing Brook Street and Frogmore Street, along the Western Road

leading to Aylesbury, passing Miswell Lane and Chapel Street, and

terminating at a point opposite the Britannia Inn, in the parish of

Tring in the same County.

Tramway No. 1 will be a single line, except at the following places,

where it will be a double line:― From a point 4 chains measured in a

south-westerly direction from the commencement of the Tramway for a

distance of 3 chains measured in a south-westerly direction.

From a point opposite the road leading to Tring Grove, for a

distance of 3 chains measured in a south-westerly direction.

From a point 4 chains measured in a north-easterly direction from

the termination of the Tramway for a distance of 3 chains measured

in a south-westerly direction.

Tramway No. 1 is proposed to be laid that for a distance of 30 feet

and upwards a less space than 9 feet 6 inches will intervene between

the nearest rail of the tramway and the outside of the footpath on

both sides of the road, from a point 1 chain measured in a

south-westerly direction, along the High Street, Tring, from

opposite the entrance to the Parish Church, to a point 3 chains

measured in a north-easterly direction, from opposite the entrance

gate to Elm House, Tring.

Tramway No. 2, commencing at the termination of Tramway No. 1, and

passing thereby in a westerly direction along the road to Aylesbury,

down the Tring Hill, over the Grand Junction Canal, through the

village of Aston Clinton, along the street known as Akeman Street,

past the village of Broughton, over the Grand Junction Canal, and

thence into the town of Aylesbury, passing Exchange Street and

Station Street, along the New Road, and terminating in the town of

Aylesbury, in the County of Buckingham, at a point 3 chains measured

in a north westerly direction from opposite Britannia Street,

Aylesbury.

Tramway No. 2 will be single line, except at the following places,

where it will be a double line:― From a point 2 chains measured in a

north-westerly direction from the centre of the Grand Junction Canal

Bridge, Buckland Wharf, for a distance of 3 chains measured in a

north-westerly direction. From a point opposite the Rose and

Crown Public House, in the village of Aston Clinton, for a distance

of 3 chains measured in a north-westerly direction. From a

point opposite the road leading to Broughton village, for a distance

of 3 chains, measured in a north-easterly direction. From a

point 4 chains, measured in a south-easterly direction, from the

termination of the Tramway for a distance of 3 chains measured in a

north-westerly direction.

The Tramways are proposed to be laid, where practicable, on the

waste at the side of the roads.

The Tramways will pass from, through, or into the parishes or places

of Aldbury and Tring, in the county of Hertford; and Drayton

Beauchamp, Buckland, Aston Clinton, Western Turville, and Aylesbury,

in the County of Buckingham.

To authorise the promoters to construct the Tramways on a gauge of 3

feet 6 inches, and to employ animal, steam, or other mechanical or

motive power for moving carriages or trucks upon the Tramways, but

not to use on the Tramways carriages of trucks adapted for use upon

railways.

To empower the promoters from time to time to make such crossings,

passing places, sidings, junctions, and other works, in addition to

those particularly specified in this Notice, as may be necessary or

convenient for the efficient working of the proposed Tramways, or

any of them, or for providing access to any stables or carriage

sheds or works of the promoters.

To enable the promoters when by reason of the execution of any work

affecting the surface or soil of any street, road, or thoroughfare,

or otherwise it is necessary or expedient to remove or discontinue

the use of any Tramway as aforesaid, or any part thereof, to make in

the same or any adjacent street, road or thoroughfare in any parish

or place mentioned in this notice, and maintain, so long as occasion

may require, a temporary Tramway, or temporary Tramways, in lieu of

the Tramway or part of a Tramway so removed or discontinued to be

used, or intended so to be.

To enable the promoters for the purposes of the proposed Tramways to

purchase by agreement, or to take easements over lands and houses,

and to erect offices, buildings, and other conveniences on any such

lands.

To enable the promoters to levy tolls, rates, and charges for the

use of the proposed Tramways by carriages passing along the same,

and for the conveyance of passengers or other traffic of whatever

kind upon the same.

To empower the promoters to hold and acquire patent rights in

relation to Tramways.

To enable the Local Boards, Town Councils, Vestries, or other bodies

corporate, or persons having respectively the duty of directing the

repairs or the control and management of the said streets, roads and

places respectively, to enter into contracts and agreements with

respect to the laying down, maintaining, renewing, repairing,

working and using of the proposed Tramways, and the rails, plates,

sleepers, and works connected therewith, and for facilitating the

passage of carriages and traffic over and along the same.

To vary and extinguish all rights and privileges which would

interfere with the objects of the Provisional Order, and to confer

other rights and privileges.

The proposed Order will incorporate all or some of the provisions of

the Tramways Act, 1870, subject to such alterations and

modifications as may be deemed expedient.

On or before the 30th day of November instant, plans and sections of

the proposed Tramways and Works, and a copy of this advertisement,

as published in the London Gazette, will be deposited at the office

of the Board of Trade, London, and for public inspection with the

Clerk of the Peace for the county of Hertford, at his office at St.

Alban’s, and with the Clerk of the Peace for the County of

Buckingham, at his office at Aylesbury, and on or before the same

day a copy of so much of the said plans and sections as relates to

each of the parishes and extra-parochial places in or through which

the Tramways are proposed to be laid with a copy of this

advertisement as published as aforesaid, will be deposited in the

case of each such parish with the Parish Clerk thereof, at his

residence, and in the case of each such extra-parochial place with

the Parish Clerk of some parish immediately adjoining thereto, at

his residence.

Printed copies of the draft Provisional Order will be deposited at

the Board of Trade on or before the 23rd December next, and printed

copies of the draft Provisional Order when made, may be obtained on

application at the Office of Messrs. Sherwood and Co., No. 7, Great

George Street, Westminster, at the price of one shilling for each

copy.

Every Company, Corporation or Person desirous of making any

representation to the Board of Trade, or bringing before them any

objection respecting this application, may do so by letter addressed

to the Assistant Secretary of the Railway Department of the Board of

Trade on or before the 15th of January next, and copies of such

representations or objections must at the same time be sent to the

Promoters, and in forwarding to the Board of Trade such objections,

the Objectors or their Agents should state that a copy of the same

has been sent to the Promoters or their Agents.

Dated this 18th

day of November, 1887.

JOHN BATTAMS,

71, Eastcheap, London, E.C.,

Solicitors for the Promoters.

SHERWOOD and CO.,

7, Great George Street, Westminster,

Parliamentary Agents. |

――――♦――――

THE WIRELESS − PRO. AND CON.

We can only consider in a short paragraph the results of “wireless”

from a religious point of view. In favour of it are the facts

that it has enabled thousands of invalid and agèd people to hear a

religious service from which perhaps they have been cut off for

years and the remainder of their life. Many others, also, who

never attend a place of worship have heard a good sermon each week

and a religious service. In the near future, too, probably it

will be possible to broadcast a service to those thousands of our

own country men and women who are living in isolated parts of our

Empire, and who hardly ever see a clergyman.

We are also told by parents that the “wireless” keeps their young

people at home on weekday evenings when without it they have sought

amusement outside the home. Anything which strengthens home

life is valuable. On the other hand, the wireless keeps people

at home on a Sunday evening also when they would have gone to

Church.

Now, listening in an arm chair to a service at your ease, however

much you try to enter into the service, is not the same as going to

Church. No doubt you can hear a better sermon on the wireless

than you get at your own Church, but that is not the point.

Such an arm chair religion is of little value. We ought to go

personally to God’s House regularly not merely to hear a sermon, but

to maintain the public witness to God before the world, but above

all “to render thanks for the great benefits that we have received

at his hands, to set forth his most worthy praise, to hear his most

holy Word, and to ask those things which are requisite and

necessary, as well for the body as the soul.” We have lately

missed some of our regular worshippers. Will they think this

over?

Is such an easy kind of religion as listening to a “service” at home

worth much to you? And is that all you are prepared to give

Almighty God once a week? Religion has got to cost us a great

deal if it is to be worth anything to us at all. The great

insidious danger is that this vicarious kind of worship will act as

a soothing syrup to the conscience and finally put it to sleep.

Above all, no one can plead the sacrifice of the death of Christ and

receive His Body and Blood on the wireless. And that is

“generally necessary to salvation.”

――――♦――――

Ed. − On the 31st December 1926, the British

Broadcasting Company was dissolved and its business taken over by

the non-commercial British Broadcasting Corporation, ‘The BBC’.

Thus began radio broadcasting as we know it today. The

following article from the

Parish Magazine expresses fear about the detrimental impact on

churchgoers of broadcast or ‘arm chair religion’ religion.

Tring Parish Magazine August 1927

Ed. − In addition to BBC broadcasting (previous

article), 1926 also saw the arrival in Tring of mains electricity.

The next article from the Parish Magazine reports on the

replacement of the old electric generating set with mains

electricity. The generator, installed in the Vicarage

gatehouse in 1909, comprised a 4½ h.p gas engine running on coal gas

supplied by the mains (fed by the Tring Gas Light & Coke Company’s

works in Brook Street). The engine drove a dynamo that charged

a bank of lead acid accumulators. Once charged, these could

run the Church lighting system for up to 5 hours.

Tring Parish Magazine, September 1927

――――♦――――

ELECTRIC LIGHTING.

The difficulty about the electric Lighting of the Church has been

most happily solved, as it has been found possible to modify the

current of the public supply to suit our present wiring. By

means of a “transformer” we shall be able to use the system we now

have for 2 or 3 years longer, which will give us time to collect the

money for the wiring which will be required by the full power of the

public supply.

This is a great convenience as the present year has been a heavy

one, and to have found £150 or so before its end would have been a

considerable difficulty. Will people kindly remember the

“Church Electric Wiring Fund” as I believe that it is the intention

of the churchwardens to start such a fund at once? Sometimes when it

is desired to make an “offering” there is doubt as to what it should

be given, and here is something which is a real necessity for our

public religious life and to which it might be suitably devoted.

The Church authorities are most grateful to Mr. and Mrs. Kemp for

the long suffering way in which they have endured our present

private plant upon their premises, until such time as we could

mature plans for being connected with the public supply.

Tring Parish Magazine, November 1927

The faulty condition of the old cable and of other sections of the

apparatus in the Parish Church are the cause of the very poor

lighting, recently, of the main portion of the Church, and it has

become urgently necessary that the substitution of a new cable for

the old one, as well as other necessary work, be taken in hand.

The work to be done now will happily form part of the whole scheme

of re-wiring which must shortly be proceeded with, at an estimated

cost of £150. A fund has been opened and subscriptions are

appealed for without delay that the work may be put in hand as soon

possible. These may be paid into the National Provincial and

Barclay’s Banks, or to the Churchwardens.

The old apparatus has served us for eighteen years, and so it is

apparent that the present state of affairs is by no means

extraordinary.

Tring Parish Magazine, January 1928

The first part of the re-wiring and renewals made necessary by the

connecting up with the public electricity supply has been completed

in an entirely satisfactory manner by Mr. Gilbert Grace, at a cost

of £42, which amount will absorb all the present subscriptions to

the Electric Light Fund, together with the amounts realised by the

sale of the old engine and batteries now no longer required.

The transformer and its fitting have yet to be paid for, and the

greater portion of the work, to complete the rewiring scheme, has

yet to be done. Probably more than an additional £100 will be

required, and an urgent appeal is made to all member’s of the

congregation, and to others who may be interested, to subscribe

without delay to the fund now open at the National Provincial and

Barclay’s Banks. The transformer has a life of 2 years; it has

now been in use for 4 months; it is not paid for; and 4 months so

soon becomes 2 years!

――――♦――――

Tring Parish Magazine,

December 1935

A TALK ON TITHE.

The opening meeting of the new session of the the Men’s Society was

held in the Church House on Monday evening the 4th November, and we

were very fortunate in getting Mr. MacDonald to come and speak to us

on “Tithe,” a subject which in some districts has caused disturbing

incidents, and in general has given rise to a great deal of

controversy.

Mr. MacDonald began by saying that he hoped he would not send us all

to sleep (he evidently was not accustomed to the Church House

Chairs) and then made his audience sit up by stating that there is

now no such thing as Tithe.

He explained that from early times “tithes” or “tenths” of the

produce of the land had been given to the parson, but owing to the

difficulty and inconvenience of collecting the tithes in kind, Tithe

owner and Tithe payer in many cases agreed to a modus or money

payment in lieu of tithe, and that by the Tithe Act 1836 the payment

of tithe in kind was abolished, and land was assessed to tithe

rentcharge according to its then fertility or bearing capacity, the

amount payable varying with the price of corn.

The present Tithe Rentcharge thus became a charge on the land and in

1891 it was made illegal for the Landowner to make his tenant

responsible for its payment.

It could be said on behalf of those who objected to pay “tithe,”

especially in the Eastern Counties where “tithe” is heavy, that when

the tithe rentcharge was assessed in 1835 the land there was good

corn land but that now in many cases it had fallen down to grass,

and the tithe rentcharge perhaps represented more than the present

value of one-tenth of the value of the produce, but it seemed that a

great many of the objectors had bought their land recently with full

knowledge of the charge thereon, and did take, or should have taken,

this into account in arriving at the price paid for the land; so

that in these cases the objection was hardly logical.

Mr. MacDonald explained the difference between small and great

tithes and how the latter were often taken by the absent Rector

leaving only the small tithes for the Vicar of the Parish.

He also gave instances of parishes where there is no tithe, where

there is only Rectorial Tithe, and where there are both Rectorial

and Vicarial Tithes.

Mr. MacDonald’s personal stories and anecdotes in connection with