|

Gilbert Cannan (1884-1955) and Mary Barrie, former wife of writer J. M.

Barrie, were seeking the solitude of the countryside, which Gilbert

thought would have a beneficial effect on his work. In the early

summer of 1913, the Cannans, together with their two enormous dogs,

took up residence in the tile-hung Mill House that stands to the

right of the entrance drive to the mill. But more important to

Gilbert was the windmill, which he intended to turn into his own

private haven and place of work. He wrote to a friend “We’ve taken a

windmill to clear out to in the Chilterns, and I’m to have a study

looking towards the four corners of the Heavens and the earth”. Cannan obviously drew his desired inspiration from

the panoramic views of the surrounding countryside, for during this

period novels, plays, poetry and translations poured from his pen

and he succeeded in achieving a modest literary reputation.

Inside the windmill, the local carpenter was engaged to fit shelves

in the study for the Cannans’ huge collection of books; a tall desk

was installed where he worked — either standing or sitting on a

high stool — and a Russian artist friend painted a frieze around the

walls. Other aspects of interior design were suggested and carried

out by Mary. She decorated the walls of the circular living room

with great flower patterns, cutting out and pasting up each flower,

fern and leaf herself; although not to everyone’s taste, all their

guests admired her originality. A spiral staircase was fitted and a

dado of brightly-coloured frescos adorned the dining room, none of

which now remain.

At first,

the couple enjoyed their rustic life. The garden of the Mill House

was already planted out and Mary acquired part of a paddock

adjoining the mill to enlarge the grounds. A courtyard was laid and

tubs planted with shrubs and flowers. Gilbert joined the local

cricket club and occasionally played bowls in the adjacent The Full Moon

public house, including in the party any of the Cannans’

frequent weekend visitors.

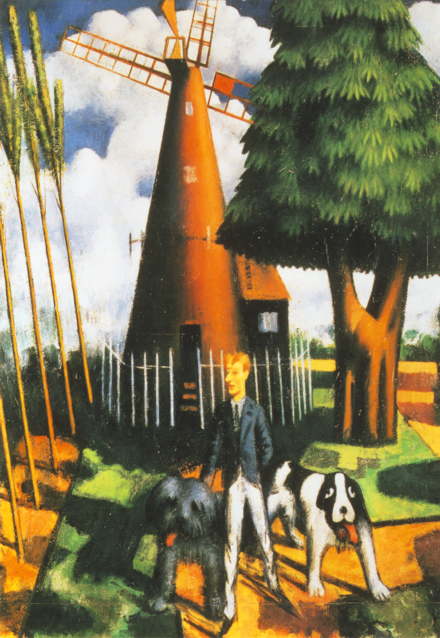

Fig. 9.7: Gilbert Cannan at

his Windmill

Cholesbury has probably never seen such a lively time as the period

of Gilbert Cannan’s occupancy of the windmill. Weekend evenings saw

pastimes, such as poetry readings, playing the pianola,

philosophical talk and performances by the guests of plays written

by Gilbert. The artistic luminaries of the day who stayed there, or

in the village, included writers D. H. Lawrence, Katherine Mansfield

and Compton Mackenzie; and the painters Vladimir Polunin and Mark

Gertler. In Gertler’s colourful painting (fig. 9.7), the tapering windmill flanked by trees provides the

background to the main subject who is depicted standing between his

two dogs, one of which, Porthos, was used as the model for Nana in J.

M. Barrie’s Peter Pan. Reputed to have taken two years to complete,

the painting is now on display in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

But the idyll was not to last. The Great War broke out; Gilbert’s

fragile mental health began to show the first signs of collapse; his

marriage was failing, eventually ending in 1918 following an affair

with their maid, who became pregnant.

Following WWI, Gilbert wrote and translated a great deal. He also

travelled and during an absence in America his mistress, Gwen

Wilson, a radiantly beautiful art student, married the third member

of what had become a ménage à trios, the industrialist and financier

Henry Mond. The result was that Cannan suffered an irreversible

mental breakdown and spent his remaining years confined to a private

psychiatric hospital, where he died in 1955.

THE WINDMILL’S LATER LIFE

|

|

|

Fig. 9.8: Doris

Keane (1881-1945), actress |

Shortly after the Cannans left the mill in 1916, the tenancy was

taken by one of their friends, the American actress Doris Keane, who used the windmill as her country retreat. The

artistic connection continued until the 1930s when a Chelsea

portrait and landscape artist, Bernard Adams (1888-1965), conducted

an art school in the mill. A description of the mill at this time

appears in English Windmills (Vol. 2), although this was concerned

with its structural condition rather than its colourful tenants. . .

.

|

“This is a circular brick mill standing in private grounds behind

the old converted mill house . . . It last worked sixteen years ago,

when it was grinding standard flour. Since it ceased working a

cottage has been built against the mill, apparently incorporating

part of its lower floor. One of the sails was shortened at that time

as its length interfered with the work on the roof.” |

In 1937, the Windmill Section of the Society for the Protection of

Ancient Buildings stepped in to carry out necessary repairs. One

account states that the windmill was transferred to Cholesbury

Parish shortly before the outbreak of WWII., but this seems

unlikely.

Hawridge windmill experienced another change in its fortunes during

WWII., when it was used as a look-out post. What is certain is that it

afterwards fell into disrepair and dereliction. One sail blew off

during a gale in the early 1950s and another collapsed.

The mill had to wait until 1968 to be completely restored by its

then owner, Don Saunders, an engineer at British Aerospace. He

designed and built new hollow steel spars, painted red and white,

which were winched into position to replace the mill’s original

sails.

Hawridge Mill has had several owners since its post-war restoration,

with the artistic connection continuing with Mrs Saunders, a former

Tiller Girl, and Sir David Hatch, a comedian and later Managing

Director of BBC Radio.

Fig. 9.9: what might have been

the flywheel from the mill’s steam engine

The mill is now tastefully furnished as a private home with a

spacious kitchen installed in what was once the meal floor.

Some of the mill’s equipment survives in the cap; the brake wheel, a

substantial iron windshaft and its tail (roller) bearing (plates

16 and 17). That

part of the winding gear comprising the spindle, rack and pinion

together with a hand crank also remains — the fantail fitted today is for purely for show.

Downstairs in the sitting room appears a large cast iron wheel (fig.

9.9), some

eight feet in diameter, propped up against one of the walls. What

purpose it served is a mystery. The fine machining suggests a degree

of precision unlike windmill equipment, while there is no obvious

sign of wooden teeth having been attached. Furthermore, the aperture

for the spindle appears too small to accommodate an upright shaft. What it might have been

— if indeed it came from the mill — was the

steam engine’s flywheel (the 12 hp steam engine at Wendover mill is

recorded as having driven an 11ft diameter flywheel!)

――――♦――――

APPENDIX

TECHNICAL DETAILS OF

HAWRIDGE TOWER MILL

Fig. 9.9: looking upwards from

beneath the curb.

The windshaft and its tail bearing is on the

left,

the rack and pinion winding gear is on the

right

English Windmills (Vol.2), provides the following brief description

of Hawridge windmill in 1932 . . . .

“The four sails are complete, but the shutters have been removed.

The vanes of the fantail are missing, but the staging remains. The

gallery is complete. The cap is of the ogee shape and is apparently

covered with zinc sheeting. The whole of the tower is tarred.”

The ever-helpful writer on windmills, Stanley Freese, recorded the

following technical description (c.1939):

“The reefing gear was controlled by external chain and weights

suspended from a ‘Y’ wheel on the fan stage; and the fly was of the

8-vaned pattern. From this fantail a wormshaft passed horizontally

over the curb to drive a vertical countershaft, at the foot of which

a pinion engaged with the iron cog-ring upon the inner face of the

curb, as at Wendover and Quainton. In common with the latter mills,

Hawridge is provided with a ‘shot’ curb, that is to say a floating

chain of bearing rollers free of both the curb and cap; but in the

present instance the rollers are shorter and more sharply tapered

than at Wendover. They are hollow, with two slots at the end for

positioning the inner casting cone. Two check wheels are suspended

by iron arms to run against the curb beneath the cog-ring; one at

the tail, and one on the right-hand side, to correspond with the luffing gear on the left-hand. The tail bearing of the iron

windshaft is situated in the tail of the small cap, so that the

shaft actually extends back over the curb of the mill; and upon the

shaft is a two-piece eight-armed iron brake wheel measuring only 7

or 8 ft. in diameter, its wooden cogs engaging with an iron wallower

upon an iron upright shaft, but all the gear below the windshaft was

cleared out early in the war [WWI].

“There are believed to have been two pairs of under-driven stones in

the mill, driven by a wooden spur; and an additional two pairs in

the wooden building of the steam mill.” |