|

“This is another of the remaining open

trestle post mills. It is in bad condition. One of the sails remains

with its end resting on the ground, and so helping to support the

body of the mill. It ceased working before the war . . . . This is

one of a group of mills with three, instead of two cross-tree

timbers, and six, instead of four quarter bars [Chinnor

being another] . . . . This mill is not marked

on an old map of 1797, and as its appearance suggests a greater age

than one is led to suppose, it may have been brought from elsewhere

and erected on its present site.”

English Windmills, Vol. 2, 1932

Piecing together a windmill’s history

is usually much more of a challenge than locating it,

for windmills rarely attracted much attention during their lifetime and

it is not unusual to find that little or no

documentary evidence survives.

Nevertheless, when taken together, parish records, local trade directories,

newspapers, auctioneers’ catalogues and letters of the period can

sometimes provide a sketchy outline, as this

chapter illustrates. Then there are old books; fortunately, enthusiasts such as Stanley Freese, Rex Wales

and Donald Smith were around when windmills that are now long gone were

still to be seen — even if only their

remains — and they recorded for posterity what they saw and

learned about a windmill’s history, usually from people who could

remember the mill at work, or even worked in it.

Thus, what follows is sometimes little more than a mention of

some of the undoubtedly many windmills that once worked in

north-west Hertfordshire and over the county boundary into parts of

Buckinghamshire.

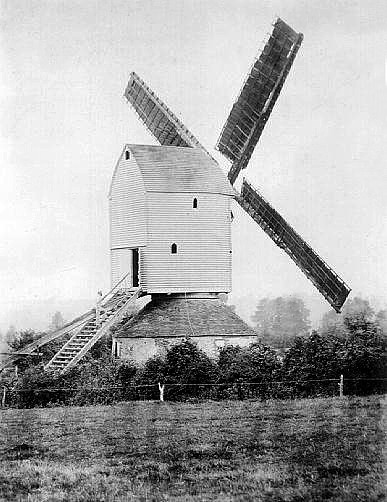

Fig. 14.2: Cuddington

post mill near Aylesbury, seen in 1894.

This post mill was demolished c.1925

TRING

From the time of Domesday until the middle of the 16th century,

streams in and around Tring drove three different watermills; so it

can be assumed that in medieval times there was probably no need to erect any

windmills, or if there were any they are unrecorded. The

watermill at Gamnel was bought by the Grand Junction Canal Company

to acquire its water rights, but when the

other watermills fell into disuse is not known. The first windmill

map symbol for

Tring appeared in 1766 on a map surveyed by the famous

cartographers Dury and Andrews.

Fig. 14.3: c.1766 —a windmill

symbol is at the centre of the map, under ‘New Mill’

(an area of

Tring which has retained that name)

and to the right of the intersection

of the present day

Dundale Road and

Icknield Way.

The windmill depicted on this map (fig. 14.3) was sited three

quarters of a mile north of the parish church, on the Icknield Way

and to the east of what is now Dundale Road; on the map, the area is

called ‘New Mill’, a name that it has retained. A windmill is also shown in this position on the Inclosure map of 1797; valued by the Commissioners at 6s.2d., it is

listed as belonging to Edward Foster’s Trustees. No other records of Tring’s old windmill on Icknield

Way are mentioned in any local records. The late local

historian Bob Grace, who

owned Grace’s Maltings in Akeman Street, claimed that a 3ft ‘Cullin

Stone’ (a name given by millers to black millstones imported from

the Cologne area of Germany) from this old post mill was set into

the courtyard of his premises.

Fig 14.5: Bryant’s Map of

1820. A windmill (unknown) symbol

appears under the “eld”

of Icknield

Before leaving Tring, it is worth mentioning that a windmill symbol appears

on Bryant’s Map of 1820

(fig. 14.5). It is also located on Icknield Way at the

junction with Dundale Road, but further

west than the ‘New Mill’ mentioned earlier. This symbol might

in fact refer to the ‘New Mill’, with either Bryant’s or Dury &

Andrews’ map containing an error as to its location. It is

also possible that Dury’s map might correctly mark the location of

an entirely different mill of

which nothing now is known, or that the ‘New Mill’ was moved.

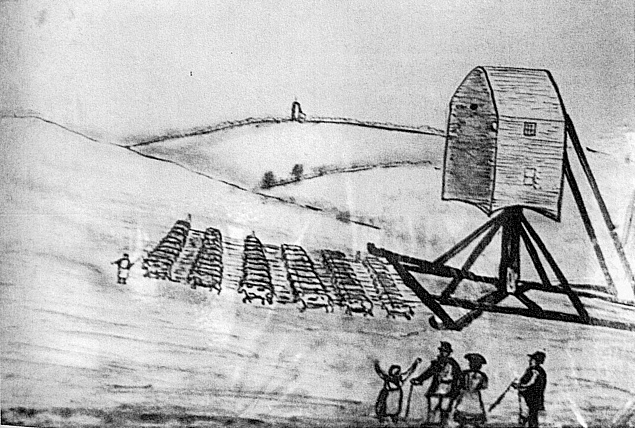

Fig. 14.4: moving a post mill

using a sled hauled by a team of oxen

Although uncommon, windmills were moved occasionally, as this

account of the procedure for bodily removing a post mill illustrates

. . . .

“If the main post and crosstrees were to be retained, they might be

removed complete with the mill carcass; the crosstrees [fig. 2.2]

would be shored up, brick piers demolished, and the trolley run

underneath the structure, which was then let down bit by bit with

jacks and levers. Sometimes in Suffolk two ‘drogues’ (or timber

wagons) were lashed together side-by-side, two arms of the

crosstrees being rested on one, and two on the other . . .”

. . . . and many horses or oxen were then teamed to haul the

resulting load. But were the mill was to be moved any

distance, this could only be achieved by dismantling it; an example

here is the smock mill at Lacy Green, which originally stood at

Chesham. In 1821, it was dismantled and reassembled some

9-miles to the west on its present site at Lacy Green (Chapter

XIII).

ALDBURY

In Aldbury the Open Village, (pub. 1987), Jean Davis, the Aldbury

historian, writes that . . . .

“. . . . in the southwest corner of Aldbury Parish, Great and Little

Windmill Fields recall the mill which would have served Pendley

Manor, but as early as 1354 it was in very bad condition.”

Two maps of Aldbury, one dated 1762 and the other 1803, show a ‘Great

Windmill Field’ and a ‘Little Windmill Field’ in an area about one and

a quarter miles south-west of the church. These fields are near both

the Tring and Wigginton parish boundaries with Aldbury, and an

account of the bounds of Tring Manor in 1650 contains what seems to

be a reference to this windmill site. . . .

“. . . . and soe a longe the highway between Aldbury ffield and

Tringe ffield and soe to Pendley Lockshops and from thence unto

Pendley gate and from thence to Windmill Corner and from thence to

old well . . . .”

These references to known landmarks locate ‘Windmill Corner’ as

adjacent to the ‘Windmill Fields’.

Even more mystery surrounds the second windmill in Aldbury. A rental

document, with an approximate date of 1501, mentions a “wynd Milfelde”, the site being about two-thirds of a mile west-north-west

of the church. Further evidence of a windmill in this position comes

from a map of the Duke of Bridgewater’s estate dated 1762 which

names a ‘Windmill Hill’. On an aerial photograph of 1972, there is a

circular crop mark in the position where it is thought to have been

sited.

A further shred of evidence can be found in the Victoria County

History of Hertford (Vol.2), which states that a windmill was

erected in Aldbury towards the end of the 16th century. In 1589-90,

a licence was asked for by Thomas Kynge to erect a cottage for the

miller “a painfull man in his calling”. This latter does not quite

agree with the other dates, but in discussing matters so long ago, a

difference of one hundred years has sometimes to be expected; all

that is certain is that there has been no working windmill at Aldbury for a very long time.

PITSTONE’S OTHER WINDMILL

The post mill at Pitstone (Chapter VI), now in the care of the

National Trust, is well known and documented. What is less known —

indeed, almost unknown — is that it once had a near neighbour,

another post mill, which was located on land that is now part of the Castle Mead estate.

The sole documentary evidence for this mill lies in an

account written during the 1930s by the windmills author, Stanley Freese. Freese admits that the mill is not shown on

standard maps of the period, “although the early 6in and 25in O.S.

outlined the mill mound without naming it”. However, local

historians at Pitstone Green Museum were able to locate the mill on

an undated tithe map, where it is shown standing adjacent to the course of the former

Marsworth to Pitstone Road.

Freese’s single type-written sheet gives a brief account of an

interview that he had with one John Tompkins, whose family drove the

mill. Tomkins told Freese that his father “had the mill until about

1861” when he left for America and that the mill met its demise

shortly afterwards. In Freese’s words. . . .

“Mr. Tompkins believes that the late Mr. Hawkins, who eventually had

Ivinghoe Mill [the National Trust mill], took the old one from his

father, but in any case it would have been only for a year or two;

for the mill ‘ran away’ in a gale whilst the miller and an old man

named Corkett were in it; and before it could be checked two of the

sails were hurled from the mill. The miller anticipated the

catastrophe and shouted to Corkett to look out, but the latter being

very deaf did not hear the miller’s shout above the gale; and found

the roundhouse, in which he was at work, falling about him, and a

sail coming through the roof. He escaped serious injury however.”

Such were the risks of windmilling, and it is coincidental that

Pitstone windmill was to meet with a similar catastrophe in 1902.

The mystery mill must have been badly damaged, for it was demolished

shortly afterwards. John Hawkins, a local farmer interviewed by Freese, had known old Corkett and although he did not recall the

mill he did remember that its brick piers remained for a time before

they, the mound on which the mill stood and its access path, which

lay adjacent to the old Ship Inn in Vicarage Road, disappeared under

the plough.

The description given to Freese was of a post and roundhouse

structure of average size, but not as big as Pitstone Mill,

nondescript in colour, with four cloth sails and a tail post and

wheel. It was equipped with both wheat and barley stones, side by

side, but it is thought not to have been a flour mill but employed

in grinding animal feed. The mill is believed to have belonged to

the Ashridge Estate and Freese thought it possible that the Estate

later purchased Pitstone Mill to replace it.

CHOLESBURY

Yet another mystery windmill was sited on the east side of

Cholesbury Common. This is shown on Robert Morden’s 1695 map of

Buckinghamshire and also that of his copyist Emanuel Bowen’s map of

1760. About a furlong south of Tring Grange Farm, the position

marked is now just over the Hertfordshire border. According to local

tradition, the exact site was not ‘Windmill Field’, which

would place it on a hillside, but in the next field upon the

hilltop. However, at the time of writing it remains a mystery, for

no remains have been discovered.

HAWRIDGE COMMON

Fig. 14.6: Hawridge smock and

steam mill

In the words of Stanley Freese, a “fine-looking though not well

designed smock mill” (fig. 14.6) was erected on Hawridge Common by

the ‘Norwich Wind and Steam Mill Company’ in 1863, and came complete

with steam engine to supplement the wind; old photographs depict an

impressive brick chimney and, by 1866, a delivery note for half a

sack of flour (at 18s.0d.) was headed “Hawridge Wind and Steam

Mill”. The chimney was pulled down in 1884.

Hawridge smock mill was

unusual in Buckinghamshire in having a square two storey brick base, above which

was a narrow wooden tower whose walls were tarred. The four white

sweeps were of the patent anti-clock double-shuttered type, and the

fantail was six-vaned.

There is no continuous and completely reliable record of the various

millers and owners of Hawridge. The Millers who can be traced through

the census returns are . . . .

|

1861 |

Thomas Moreton, miller, born Nuneaton

Charles Pedel, journeyman miller, born Wendover |

|

1871 |

Joseph

Salt, miller, born Congleton

George Salt, miller, born Warwickshire

George Wright, miller, born Cholesbury |

|

1877 |

William

Wright, miller |

|

1881 |

Harry Wright,

miller, born Tring |

Original documents show that the mill was acquired in 1871 by

Humphrey Dwight, described as a pheasant breeder from Wigginton, who

purchased it from a consortium at Great Windsor. He paid £700, which

included “a messuage, granary and premises”, the legal aspects of

the sale being handled by Smith, Fawdon & Low of Chesham and Shugar,

Vaisey & Co. of Tring.

It seems that Dwight did not prosper, for ten years later the

freehold again changed hands. Dwight (described in the 1881 Census

as a farmer of 140 acres employing 5 labourers, and resident at 24 Bellingdon Road, Chesham) called again on the services of Tring

solicitor, Arthur Vaisey, who prepared on his behalf the following

statement dated 14th February 1881 . . . .

“I the undersigned Humphrey Dwight of Bellingdon near Tring having

been served with a Writ for the sum of £578.5s.2d. due from me for

principal and interest to the executors of the late Mr John Merritt

Shugar which sum is charged upon my freehold mill and premises

situate at Hawridge Bucks hereby authorise and request you to take

the necessary steps on my behalf for selling the said mill and

premises either by public auction or private contract and also to

endeavour to get any further proceedings on the said Writ stayed

pending the sale of the property.”

On 26th February, William Brown & Co. received instructions to

auction the mill, the sale being held at the Rose and Crown Inn,

Tring. The auctioneers described the property as a . . . .

“Free hold Windmill with steam power attached, driving four pairs of

stones, situate on Cholesbury Common, part in the Parish of

Cholesbury, part in the Parish of Hawridge; also capital residence

with garden, yard, and stabling. The property is in the occupation

of Mr Wright, a yearly tenant at a rent of £400 p.a.”

The sale realised exactly £600, which Humphrey Dwight was obliged to

surrender to settle the debt together with a further £20. 18s. 5d. to

cover auctioneer’s and solicitor’s fees.

The mill is believed to have been bought by Daniel, another member of the

extensive Dwight dynasty, who at some time between 1881 and

1883 replaced the smock mill with the tower mill (Chapter

IX) that stands

today. The reasons for demolishing a mill only twenty years old were

given as inconvenient arrangement; poor construction; loading floor

on the ground instead of at cart-level; and no bin floor, resulting

in grain having to be fed directly into the eye of the millstones

instead of being shot down from storage bins in the floor above. These defects probably rendered the mill unprofitable to work, and

might in turn explain the frequent change of millers. But one miller

is known to have given up the mill for an unrelated reason. Joseph

Salt met a tragic death when, helping to right a derailed locomotive

in the neighbouring Tring valley, he failed to let go of a lever

when it was released by the other workmen, and was killed as a

result.

During its demolition, the smock mill’s machinery and other parts

were salvaged to be incorporated in the new tower mill. Today, a

fitting reminder of Hawridge’s old smock mill lives on in the shape

of the logo of the Hawridge & Cholesbury Cricket Club, whose members

are fortunate enough to have a pitch on the beautiful Common.

MARSWORTH

The Domesday survey records three mills in the Manor of Marsworth. By 1292 a water mill existed, valued at £4. 9s. 4d., which descended

through various owners, eventually becoming known locally as Dyer’s

Mill. It stood in the south-west corner of the village, and

according to the Victoria County History (Vol.3), it was “turned

into a windmill”, which seems quite possible since the construction

of the Grand Junction Canal diverted the water, thereby

incapacitating all Marsworth’s watermills.

A reference of 1817 records that a Thomas Sear insured a brick and

timber wind-driven corn mill with no kiln and two pairs of stones

for £600 and an adjoining house for £200, the whole a quarter of a

mile west-south-west of Marsworth church. In 1824, members of the

Sear family leased the premises to William Pickett, shopkeeper of Marsworth. These included “a recently erected windmill on the same

site of the former watermill”.

Twenty years later Thomas Sear sold the mill to a horse dealer,

Charles Gregory, who took over the £400 mortgage. After a few years

it was sold on again to Thomas Clarke, miller of Tring, who in his

turn took over the mortgage and insurance payments, also obtaining a

second mortgage of £1,000 to erect a steam mill “adjoining to the

said Wind Corn Mill”. The Indenture included a requirement to keep

“the wind corn mill insured against loss or damage by fire, and to

run the business correctly”. By 1875 the mortgage was paid off.

Thomas Clarke died intestate, and his property was offered for sale

at the Rose & Crown, Tring; Thomas Mead, a local miller, bought the

entire premises for £1,500. According to the sale advertisement that

appeared in the Bucks Advertiser during January, 1881, it comprised

. . . .

“. . . . a Steam Mill of 5 floors fitted with a 12 hp. Steam Engine,

a 16 hp boiler, 3 pairs of stones with elevators, and all necessary

shafting and gearing, most completely fitted, and all in perfect

order; a SIDE MILL of 4 floors, communicating therewith from each

floor; a bean and drying kiln; a comfortable dwelling house, adapted

for the proprietor with all necessary fittings; a stable for 4

horses, with loft over; various convenient out-houses; good garden;

close of pasture and orchard land, together about one acre, one

rood, and one pole, upon which a lucrative business has for 28 years

past been carried out . . . .”

Thomas Mead already owned a new steam-driven mill at Gamnel Wharf,

Tring, and bought Marsworth windmill possibly as a strategic

purchase to prevent any competition with this new venture. However,

he had no use for the old windmill which was eventually demolished

c.1919.

Elderly residents of Marsworth, when interviewed during the 1930s,

recalled that the windmill’s sails were torn off in a gale in about

1845 and the gear so damaged that for a considerable time the mill

was unworkable. A man who assisted with the demolition remembered it

being built of red brick, four storeys high but without a stage, and

with four patent sweeps and the usual fantail.

OTHER VANISHED WINDMILLS

|

|

|

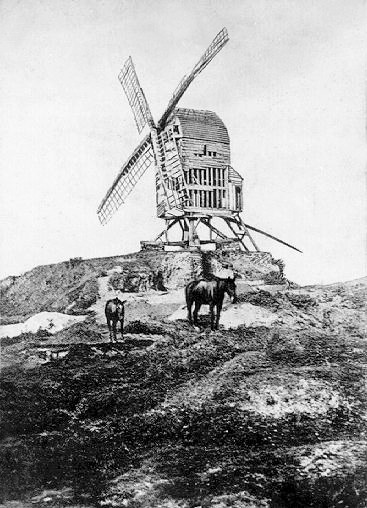

Fig. 14.7:

Parson’s Mill, Brill |

In his book Hertfordshire Windmills and Windmillers, Cyril Moore

refers to several windmills in the broad locality of Tring about which

very little is known. That at Abbots Langley, believed to have been in

the vicinity of Catsdell Bottom, was standing in 1912 in a derelict

condition. There is evidence of two windmills at Berkhamsted, one of

which, a post mill, is depicted in an 18th century view of the town

that places it in the vicinity of Millfield Road. The windmill at

Little Gaddesden probably disappeared in antiquity, with old

references to a “Mill Field” to the south-east of the church being

its last trace.

To the north of Tring, there were windmills at, among other places,

Brill and Quainton — in addition to those that remain at both

locations — and at Wing, Wingrave and Waddesdon.

At Brill, the famous post mill that stands on the Common once had a

near neighbour. Built in 1634 and latterly known as Parson’s

Mill, it stood on the opposite side of the road. Unlike its

neighbouring post mill, Parson’s Mill did not have a roundhouse, but

at the time of its demise and on the grounds of comparable age, the two mills were probably similar in other respects. Struck by lightening in 1905, the mill

was demolished in the following year; the mound (‘tump’) on which it

stood (seen in the photograph) remains visible.

|

|

|

Fig. 14.8:

Waddesdon mill stood on Windmill Hill |

There is no record of when Waddesdon Mill was built, although it was

standing in 1834, for in Cook’s History of the English Turf the

author describes a steeplechase run in that year over a course from Waddesdon windmill to Aylesbury Church, while from a slightly

earlier period the account book of the Aylesbury millwright William

Cooper (Chapter V) records that he undertook work on a windmill at “Wadsdon”;

it is also believed that John Hillsdon of Tring was in some way

connected with the mill. [6] The mill is said to have been a particular favourite of Miss Alice

de Rothschild, who had inherited the great Waddesdon estate from her

brother, Baron Ferdinand. In its latter day this attractive

tile-hung windmill was said to be more ornamental than practical,

for local rumour has it that if the wind was favourable it was set

to work for no better purpose than to greet Miss Alice on her return

to the village after her absences abroad, and she is believed to

have paid for its restoration in the early years of the 20th century

(c. 1905). English Windmills (Vol. 2) records that (c.1930) the mill

was “slowly decaying”; according to Stanley Freese, it met its fate

when “it was dynamited by the Baron’s nephew for no apparent reason

in the summer of 1932”.

The history of the fine tower mill that stands near the village green

at Quainton is

well known; much less is known about the village’s other

windmills, of which there were several over the centuries although

only scant references to the earliest of them exist.

The first windmill about which there is firm information

stood at Blackgrove Farm to the south-west of Quainton village.

Owned by Thomas Anstiss,

who later erected Quainton tower mill (Chapter

XI), ‘Banner Hill Windmill’ opened for business on the 16th May

1797, having been erected in the short space of 57 days. Following

completion of the tower mill, Anstiss sold Banner Mill, which was

later dismantled and moved to Mursley (c.1840) where it continued in operation

until the 1890s, when it burned down in mysterious circumstances.

Another post mill, ‘Curtis’s Mill’, named after its owner Thomas

Curtis,

stood at Quainton on Seech Field near to the railway station.

Built towards the end of the 18th century, she was an open-trestle post mill with four cloth sails,

which drove two pairs of stones (4ft 4ins and 3ft 10 ins) and a

dressing machine. According to the windmill researcher Stanley Freese, “She was a nice

little fast-running mill, she would always go, even when the giant tower

mill refused to start”.

“QUAINTON. — On Wednesday morning last the

old mill belonging to Mr. Thomas Curtis at Quainton, was discovered

to have been broken open, and about four bushells and a half of

flour, with two sacks, stolen therefrom, the property of Mr. W.

Cooper, baker, of Quainton. Information having been given to Mr.

Read, the constable, he was soon on the spot, and found footmarks

near the mill which he traced over the new inclosed fields and quick

sets in a direction for Waddesdon, nearly up to some houses occupied

by Jos. Kibble and F. Cripps, and with the assistance of Mr. Paine,

another constable, made a search of the above houses and succeeded

in finding about the quantity of flour lost lost, when Kibble and

Cripps were apprehended, and taken before the Rev. E. N. Young the

next day, who after hearing the dispositions of the witnesses,

committed then to Aylesbury goal to take their trial for the offence

at the next Quarter Sessions. Mr. Cooper and other witnesses were

severally bound over to appear against them. This mill was broken

open in February last, on which occasions a quantity of meal was

stolen therefrom.”

Bucks Herald,

19th April 1845

The mill was sold at least twice

during her life; in 1854, she was put up for auction together,

with a granary for 100 sacks of flour and stables. Whether she

sold or not is unknown, for the following year a newspaper article

describes an . . . .

“. . . .

excellent supper at the George Inn given by Messrs

Hillsden,

Millwrights of Tring, on closing the works of a new mill belonging

to Messrs Curtis of Fulbrook, on the site of the old mill which

stood for a number of years in Seech Field. Mr Huckvale, the

tenant, presided.”

Bucks Herald,

10th November 1855

One assumes from this that the “old mill” was in a poor state

of repair and was substantially rebuilt, for the “new mill”

was unlikely to have been of the post mill type. In 1870,

Curtis’s Mill was put up for auction, on this occasion as part of a

larger lot:

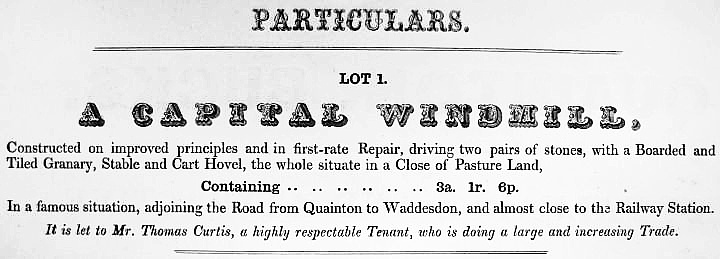

Fig. 14.9: The auctioneer’s

particulars for sale held on the 9th June, 1870,

at the White Lion

Inn, Quainton

In February 1892, the Mill was again put up for Auction — according

to the advertisement, Thomas Curtis remained the “proprietor”)

— and in September 1897 it was advertised to let. Over a

century of milling on the site came to a close at some time around

1900, and in 1912 the mill was blown down in a gale.

Wing’s windmill is marked on the 1770 and 1788 Thomas Jeffery maps

of Buckinghamshire situated on the northern side of Aylesbury Road.

The windmill had ceased operations by 1798 when it was noted as “due

to be taken down immediately” in the Posse Comitatus of that year.

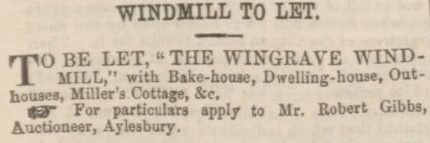

Fig. 14.10: Bucks Herald,

4th July 1863

The smock mill at Wingrave stood at Windmill Farm. It had been moved

from Whitchurch in 1809 and operated at Wingrave until about 1872,

when it was replaced by a steam mill elsewhere in the village. In

December, 1841, the Aylesbury News announced that . . . .

“Wingrave Windmill — the above mill having undergone extensive

repairs and improvements W. Burton begs to inform his friends that

he will work day and night (wind permitting) to fetch up his arrears

of grinding”.

The windmill’s sails evidently came very near to the ground, for it

is recorded that they once killed a passing pig.

At Wendover, a windmill is marked on maps by Jefferys (1768) and by

Andrews and Dury (1809) standing upon the high ground adjoining

Hale Road and almost opposite the east end of Chapel Lane, about a

quarter of a mile north-east of the Parish Church. The name of the

field where the mill stood is Snail Hill, but nothing else is known

about it.

These are just a few of the windmills that once graced our locality

and that gradually fell into disuse and decay as industrialisation

progressed and our way of life changed. An article in the Home

Counties Magazine (Vol. II., 1900) gives a contemporary view of

these romantic, but sadly vanishing landmarks . . . .

“With the increasing application of steam to milling purposes, and

the improved means of transport of foreign flour, it is pretty clear

that the days of windmills, if not quite over, are rapidly becoming

fewer, and at no very distant date most of the numerous picturesque

examples now left in the Home Counties will have fallen victims to

neglect and decay, or have been swept away to make room for more

utilitarian buildings. . . . the old windmill on Mitcham Common is

likely to disappear before long. For so many years it has been one

of the chief landmarks of the Mitcham district, and especially of

the heath upon which it stands, that its removal can hardly fail to

produce that feeling of regret which is inseparable from the

destruction of old and familiar features in a landscape.”

Where a windmill has left any trace at all, it is often in nothing

more than a name, the significance of which has long been forgotten.

Fig. 14.11: Croxley Green

windmill

Croxley Green Windmill was built c.1860. The mill was working

by wind until its sails were blown off during the 1880s, and from

1886 it was worked by steam engine only. The mill was last

used to grind wheat in 1899. The mill was equipped with four

patent sails that drove three pairs of stones. |