|

. . . . AND THOSE AROUND TRING

CHAPTER XIII.

LACEY

GREEN SMOCK MILL

“Loosley Row, situated on the Chiltern

Hills, in the southern part of this parish, is on the side of a

lofty eminence, on the summit of which is a windmill, whence is an extensive

and beautiful panoramic view, including/ Windsor castle and the

Surrey Hills on the south . . . .”

The History and Antiquities of the

County of Buckingham,

George Lipscomb (1847)

.jpg)

Fig. 13.1: Lacey Green (Loosley

Row) smock

mill

Smock mills were most prevalent

in the south-east, particularly in Kent, where ‘Union

Mill’ at Cranbrook has the distinction of being the tallest in the U.K. Although there were other

examples of smock mills in Herts and Bucks, only three are recorded in this

area; those at Hawridge and Wingrave are long gone, but an example

survives at Lacey Green near Princes Risborough, which has the distinction of being the

oldest of its type in the country. [21]

Originally referred to as Loosley Row windmill, the adjacent hamlet

of that name was later absorbed into the expanding village of Lacey

Green. The mill is an exceptionally early example of its

type, being contemporary with the post mills at Pitstone and Brill:

“This is an octagonal mill with a brick

basement and a timber body . . . .

Even before the actual date of Looseley Row Mill (or Lacey Green

Mill as it is now called) was authenticated, the mill was recognised

from its primitive equipment to be of an exceptionally early date,

and there can be no doubt that the massive compass arm brake wheel

and other gear are part of the original machinery with which she was

equipped in 1650. The very existence of smock mills at so

early a date was not previously established, but the deeds leave no

room for doubt in the matter; and they provide us incidentally with

the knowledge that the mill was removed from Chesham, by order of

the Duke of Buckingham in the year 1821 . . . . The numbered timbers

on the tower indicate that it was dismantled for removal and

reassembled. ”

Unpublished manuscript by Stanley Freece (1939),

the Centre for Buckinghamshire Studies.

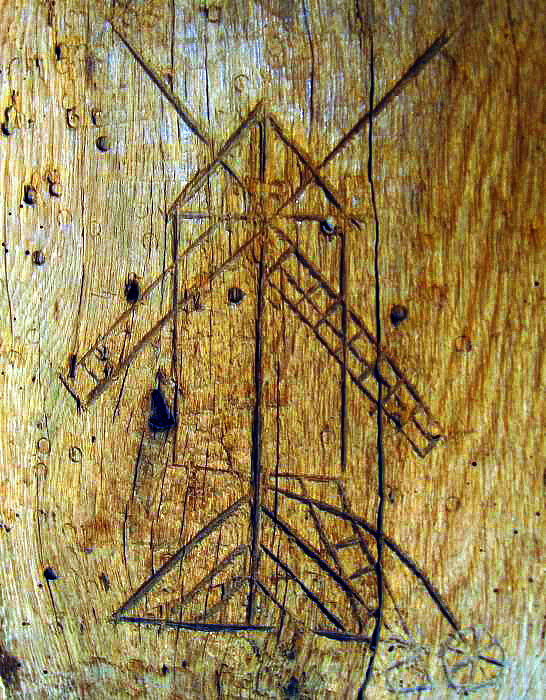

Fig. 31.2: millwright’s

graffiti?

A somewhat odd feature that immediately strikes visitors, is that

entry to the mill is through a basement — in fig. 13.1, the doorway

is on the right of the mill beneath the white sign. The mill’s

brickwork foundation stands about 2½ feet above the ground, but the

floor within is sunk, the basement being entered down a small flight

of steps. Another interesting feature is the carvings in the

windmill woodwork, presumably made by millwrights who at some time

in the distant past worked on the mill. Curiously, that

depicted in fig. 13.2 is an open trestle post mill rather than a

smock mill. |

.JPG)

|

Fig. 13.3: Lacey Green

mill looking up into the cap. On the left is the brake wheel,

at the top the windshaft, and above to the right, the wallower.

The machinery at Lacey Green is wooden, unlike the later mill at

Quainton, iron being restricted to a reinforcing role.

The mill predated the invention of the fantail,

[22] cap originally

being turned to wind by hand using an endless

chain. The existing fantail is a later addition. |

|

“The mechanism has indications of

being rather greater antiquity than is usual in a smock mill.

Both the brake wheel and the great spur wheel are of a type that

must have been becoming obsolete in the seventeenth century.

The brake wheel is large, 9 feet 8 inches in diameter, and this, the

great spur wheel and the wallower are entirely of wood, the spokes

of oak, the rims of elm, the cogs and teeth of beech. Both

wind shaft and the main shaft are of wood, the former being 20

inches in diameter at the brake wheel and the latter — an octagonal

shaft — being 14 inches across the flats.”

English Windmills, Vol. 2, by

Donald Smith (1932) |

.JPG) |

.JPG) |

|

Fig. 13.4: top left is a

‘stone

nut’

driven by the

‘great

spur wheel’

(right). The chute

in the foreground

delivers grain to the hopper beneath, from where it is trickled

into the eye

of the millstones for grinding. See figs

3.8 &

3.9. |

Fig. 13.5: another view of the

mill’s

‘overdriven’

(from above) stones.

Top left is the great spur wheel engaging

with a wooden stone nut.

The metal shaft

drives the runner stone. |

.JPG)

|

Fig. 13.6: looking up into the cap at two of the

centring wheels. Fairly closely spaced roller wheels carry the

cap upon the iron curb, whilst two large eight-spoked centring

wheels are attached to the tail-part of the cap-frame; two others

are at the ends of the sprattle beam and two in between on

projecting spars. |

|

|

.JPG) |

|

Fig. 13.7: the basement of the

mill (the meal floor) showing

the miller’s

desk and the meal bin. |

Fig. 13.8: the

‘upright

(or main) shaft’

above which is the great spur wheel.

The upright shaft revolves in a thrust bearing

fixed to the sprattle beam (the large beam immediately

above). |

|

|

|

Fig. 13.9: in

glory days — two patent and two simple sails. |

|

|

|

Fig. 13.10: Lacey

Green mill, pre-1932. |

In 1895, the mill was badly damaged in a thunderstorm and, at a time when windmilling was in decline, it’s no small wonder that

it survived such a setback:

|

“THUNDERSTORM.

— The storm of the 30th ult. was very severe here, and

did considerable damage to the windmill belonging to Mr.

Geo. Cheshire. The lightning struck the mill,

taking off several boards from the upper part and

tearing up the leaden plates which cover the angle

joints of the boarding all down one side. One of

the sails was destroyed; the chief timber, 10 inches by

10, was split from end to end, about eight feet of it

being splintered to atoms, and scattered far and wide

all round the mill, some of the pieces being picked up

over a quarter of a mile away. The supporting

beam, seven inches square, was also split throughout its

entire length. The copsing iron around the end of

the sail ⅝ inch by 1¼, was cut in half and hurled over a

hundred yards away. The woodwork was blackened,

and had it not been for the heavy rain the mill would no

doubt have been set on fire. The accident is all the

more unfortunate seeing that on March 24th all four

sails were blown down and destroyed by a gale, and Mr.

Cheshire had just had a new set made; in fact, two only

were in position, having been put up a few days before

the storm.”

The Bucks Herald,

8th August 1895. |

The

Cheshire family were the last millers, the windmill last being used for

milling in 1914-15. Following WWI., it was for a time used as

a week-end cottage, but by

1932 it was in a parlous state and in danger of collapse:

|

“The weather-boarding has been

covered with a patent roofing material. The

timbers in the tower are so eaten with woodworm and

attacked by rot that the mill is in imminent danger of

collapse. The cap was originally turned by hand by

use of an endless chain, but a fantail was added later.

This came down with the weight of snow on Boxing day

‘some winters ago.’ It had two common sails and two

patent sails and a fantail. The two common sails

have fallen off, as has the fantail also. The mill

is now leaning badly.”

English Windmills,

Vol. 2, by Donald Smith (1932). |

The Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings organised the

repair and strengthening of the structure, which took place in

1934-5. This work included fitting extra corner posts

bolted to the old timbers and set in concrete foundation blocks,

refurbishment of the cap, and painting the exterior of the mill.

But without a constant programme of upkeep, a wooden structure of

this age inevitably decays, and by the 1960 the mill was again in a very

sorry condition:

|

|

|

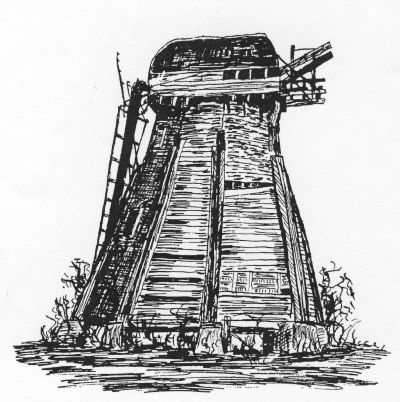

Fig. 13.11: an

artist’s

impression of the mill in 1967 |

“Now used as a store for straw

bales its condition is rapidly deteriorating. The tower has an

increasingly pronounced lean, which suggests that it may be unable

to withstand too strong a wind from any unfavourable quarter.

Any rodents attracted by the straw could be an additional hazard to

its structural integrity.”

Bucks Life, March 1967 |

A survey carried out by Christopher Wallis during

1967-68, established that restoring the mill was feasible. In

1971, the mill was leased by the Chiltern Society for a period of 25

years, and a team of volunteers began restoration, which continued

over the following 12 years. On 23rd April 1983, the mill was

opened at a ceremony conducted by the Actor Bernard Miles.

Since then, the mill has been placed in sail occasionally and flour

has been ground. |

Fig. 13.12: Lacey Green

windmill today, simple sails on all sweeps

――――♦――――

CHAPTER XIV.

|