|

. . . . AND THOSE AROUND TRING

CHAPTER II.

TYPES OF WINDMILL

Setting aside prairie wind pumps, wind turbines and other recent

developments, traditional windmills fall into three broad

categories, the ‘post mill’, the ‘smock mill’ and the ‘tower mill’.

POST MILLS

|

Fig. 2.1: A post

mill could be revolved around its central trestle to

face the sails into the wind using the tail pole

(protruding at the rear), an action called “winding”.

This open trestle post mill stood on Bledlow Ridge near

Chinnor. It was damaged and ceased working

in 1913, and was pulled down in 1933. |

Post mills were the earliest type of windmill to reach Britain,

probably late in the 12th century. They are so named because the

body of the mill is supported on and revolves around an upright

post. This enables the mill to be turned to face into the wind ― a

task called winding or luffing ― where its sails can generate the

most torque. [2] Many examples remain throughout Western Europe, those

at Pitstone (plate 1), at Brill (plate 4) and at Chinnor (plate 7)

being nearest to Tring.

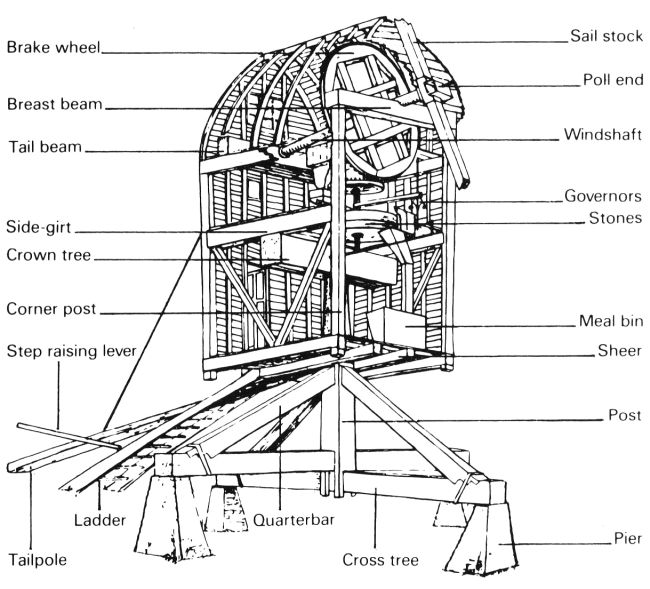

Fig. 2.2: the parts of an open

trestle post mill

The mill’s supporting post needs to be a substantial piece of timber

to carry the weight of the mill’s superstructure and machinery. That

which supports Pitstone mill was cut from a single tree, some 17

feet long by 33 inches diameter at its base, comparable in girth to

a sailing ship’s mast. The post is capped with a bearing,

which permits rotation and, via a massive wooden

cross-beam called the ‘crown tree’, supports the full weight of the

mill.

In fig. 2.2, the post appears to rest upon the cross-trees beneath

it, but this is not so. Were it to be, the entire weight of the mill

would bear down on their centre, which would eventually fracture

under the pressure. Thus, the post is suspended slightly above the

cross-trees by four ‘quarter bars’, which are mortised into it and

which also maintain its vertical position. By this means the mill’s

weight is transferred downwards evenly through each of the quarter

bars and onto the four

brick piers. The cross-trees, which are held in a permanent state of

tension by the outward thrust of the mill’s weight, prevent the

quarter bars from spreading, a clever resolution of forces.

Fig 2.3: main post, Pitstone

Mill, Buckinghamshire

Fig. 2.4: base of main post and cross

trees, Pitstone post mill, Buckinghamshire

Many post mills eventually had a brick roundhouse built about their

base (plate 4) to protect their timber supports from the

weather and to provide a covered loading bay. Those without a

roundhouse are usually described as ‘open trestle’.

Fig. 2.5: open trestle post mill at

Brill -

it later acquired a

roundhouse

SMOCK MILLS

Due to its distinctive sloping sides, usually six or eight in

number, this type of windmill came to be named after the canvas and

cotton smocks worn by farm labourers of the time. As with the

earlier post mill, the sides of a smock mill are clad with

horizontal weatherboarding, although there are some examples of

vertical cladding. The mill’s wooden body sits on a brick base to

protect it against rot and to provide support for its upright posts. The base can be a substantial structure, that supporting Union Mill

(fig. 2.6) being a four-storey building.

Fig. 2.6: Union Mill, Cranbrook,

Kent, Britain’s tallest smock mill -

built in 1814, it is now open to the public

The main internal structure of a smock mill consists of its cant or

corner posts (plate 11), which extend to its full height, converging

as they go up. The cant posts are secured at the bottom to a wooden

sill, which is fixed firmly to the brick base. This joint between

post and sill poses a problem; because the cant posts lean inwards

they throw the mill’s weight outwards at the sill, where a weak

joint can result in posts slipping away and toppling the mill.

Unlike the post mill, in which the whole body of the mill needs to

be turned to wind its sails, only the top, or cap, of a smock mill

needs to rotate. The small cap also allows better airflow around the

sails, which contributes to a more efficient and stable source of

power, especially when winding is performed automatically by a small

windmill at the rear of the cap known as a fantail (see fig. 2.6).

Because the body of the

mill doesn’t have to be rotated, it can be larger than a post mill, thus allowing

more space for machinery.

Smock mills are found throughout Western Europe; in the U.K. they

were particularly common in Kent. The nearest smock mill to Tring is

at Lacey Green near Princes Risborough (Chapter

XII.).

TOWER MILLS

|

|

|

Fig. 2.7: Quainton tower

mill prior to restoration |

The earliest record of a tower mill in Britain dates from the late

13th century and refers to a mill at Dover, possibly at the Castle.

In that age, windmills were sometimes built on the sides of castles

and of towers in fortified towns to protect them from attack.

A tower mill differs from a smock mill in that it is of brick or

stone construction and usually round in shape, although there is a

fine example of an octagonal tower mill at Wendover (plate 22). Because of its masonry construction, a tower mill requires

increasingly massive walls towards its base to support the weight of

the upper storeys; those at Wendover mill are three feet thick at

the base. It is therefore unsurprising that tower mills were much

more expensive to construct than wooden post and smock mills, and

probably for this reason they did not become prevalent until the

18th and 19th centuries. However, this type of construction offers

the advantage of a more robust frame that can support larger sails

and resist harsher weather.

In common with the smock mill, the tower mill is topped by a

moveable cap, that at Stembridge Tower Mill at High Ham, Somerset,

being the last example of a thatched cap.

The nearest tower mill to Tring is Goldfield Mill (Chapter

VIII) on Icknield Way, near to the junction with Miswell Lane. Slightly

further afield are examples of tower mills at Hawridge (Chapter

IX)

and at Wendover (Chapter X). These three mills have been converted into private

dwellings, but the tower mill at Quainton (Chapter

XI) has been restored to

working order and is open to the public. |