|

THE LIDDINGTON FAMILY

About this time William took as his assistant a nephew, 16-year old

Thomas Liddington, who by the mid-1870s had moved his family into

Mill House and had also acquired sufficient experience to be classed

as a ‘master miller’. Thomas worked the mill assisted by Henry Liddington and Harry Robinson, who lived next door. By then milling

was not Thomas’s sole business activity; dealing in corn and

retailing flour and other foodstuffs had also become important.

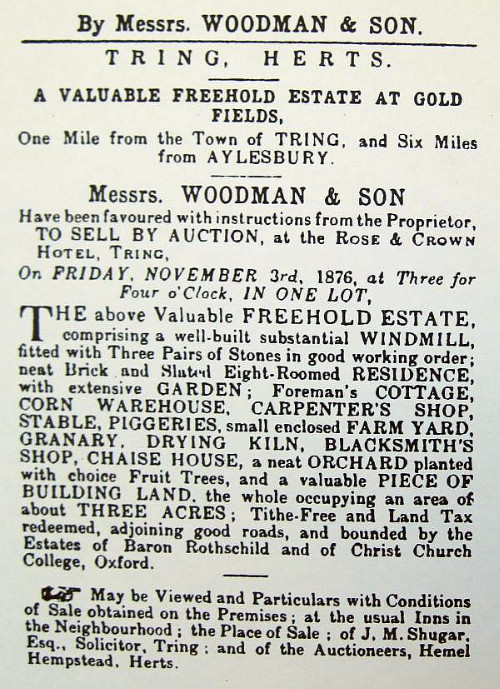

In 1876 the mill was put up for sale by auction, being described in

the particulars as a complex covering a three-acre site . . . .

Fig. 8.3: auctioneer’s

particulars of Goldfield Mill in 1876

Although not recorded, it appears that Thomas Liddington bought the

property. In retrospect, this proved to be a poor investment, for by

then milling was becoming a more highly mechanised trade and as the

years passed Goldfield windmill could not compete favourably in the

flour trade with Thomas Mead’s increasingly modern steam mill at Gamnel Wharf. In 1888 Thomas Liddington was forced to file for

bankruptcy, the application being heard in Aylesbury County Court

where it was recorded that his liabilities amounted to £1,176. 3s. 3d.

with a deficiency of £269. 11s. 7d. Described as a miller and farmer,

Thomas claimed that the causes of his failure were a decline in

trade, bad debts and other losses incurred due to his horse and

cattle dying. But this was not the only disaster to befall the Liddington family, for Henry’s dealings with customers were not

always scrupulously honest (see Liddington in

Chapter IV).

JAMES WRIGHT,

GOLDFIELD’S LAST MILLER

Who held the mill during the next few years is unknown, but after

1888 it was worked by White & Putnam, a partnership that operated

several local mills. At some stage — the records of exactly when are

conflicting — James Wright, the miller at Hastoe steam mill, about a

mile and a half from Tring, took over at Goldfield. He is shown as

being miller at both sites until about 1902 by which time he had

moved to Goldfield.

Being familiar with steam milling it was natural that James should

use auxiliary power at Goldfield and a 6 hp steam engine was duly

installed to work a pair of grinding stones, the windmill driving an

oat crusher to provide animal feed when the wind was favourable.

James Wright’s son, Herbert, born in the Mill House in 1897, is

quoted as saying . . . .

“. . . . when I was ten years of age I was strong enough to stoke

the engine boiler and maintain the water pressure as well as help

the miller dress the stones when they had to be sharpened.”

Herbert Wright goes on relate that during his father’s tenure at

Goldfield, the mill was owned by Thomas Butcher & Son, bankers, of

Tring High Street. How Butcher’s Bank [13] came to own the mill is

unknown, but it seems possible that they acquired it following

Thomas Liddington’s bankruptcy, perhaps as a foreclosure on an

outstanding mortgage.

The two systems of wind and steam power ran in tandem until around

1904 when the sails of the windmill were removed. Even so, it could

be that the milling business was still not yielding sufficient

profit, for two years later the Bucks Advertiser reported that over

an acre of grazing land at Goldfield had been sold for the sum of

£9. 2s. 6d.

The viability of the mill at this time appears to have depended

largely upon a contact with the Rothschild Tring Park estate for

crushing oats as for animal feed on its many farms. The contract

ending in 1908, James left Goldfield to take over the tenancy of

Brook End water and steam mill situated some three miles away on the

border of Ivinghoe and Pitstone, taking its water supply from the

Whistle Brook. He is recorded here in 1911 as ‘miller, baker and

confectioner’, but Herbert Wright records that after

his father took over Brook End watermill, [14] “he was forced to give up”

in 1913, being unable to compete with the large milling firms.

THE WINDMILL ABANDONED

Goldfield mill was then put up for auction by William Brown & Co.,

The Bucks Herald reporting that . . . .

“Considerable interest was manifested in Tring and the surrounding

district regarding the sale of Goldfield Windmill, one of the most

well known landmarks in the neighbourhood. The property comprised

the windmill; two dwelling houses; numerous outbuildings; and a

valuable meadow of about two acres, with a long frontage to Miswell

Lane. The property stands at a high and healthy elevation and

commands most perfect scenery of the Vale of Aylesbury and the

Chiltern Hills, and the downs and woodlands of the Ashridge estate. Messrs. W. Brown & Co. submitted the whole property by auction on

October 30th but the bidding did not reach the reserve figure and is

now to be dealt with privately.”

In 1911 Brown & Co. again advertised the complex, but the outcome is

unknown. It is likely that milling had ceased following James

Wright’s departure, for by this time small milling concerns saw

their business dwindling in the face of competition from much larger

and more efficient roller mills. However, the living accommodation at Goldfield continued to be used

and Miriam Wright, who in the period 1916-21 lived with her parents

in one of the cottages, remembered that during WW I soldiers used

the top windows of the mill for signal practice.

Fig. 8.4: Myril Smith, a land

army girl, ploughing during WWI.

Goldfields Mill is in the

background.

Myril lived at the ‘Hollies’ in Brook Street, now long demolished

RESTORATION OF THE GRANARY

AND COTTAGE

In 1919, the entire complex was eventually sold — it is believed for

£1,000 — to a Mrs Cunningham from Rhodesia. This lady then

constructed a dwelling for herself and her family in the granary

and attached cottage, later turning the barn into a bungalow for her

daughter. When Mrs Cunningham died in 1955, the house passed to

Peter Bell, a journalist for the British Farmer and Stockbreeder

magazine, but the windmill continued in its state of dereliction.

In 1946 the tenancy of the adjacent Mill House cottage was acquired

by a well-known local lady, Phyllis Thomas, librarian at the Akeman

Street Zoological Museum, who lived there for many years until

forced to leave by her increasing frailty (she died in 1990 aged

102). In 1973 she wrote a letter to Hertfordshire Countryside

magazine in which she said . . . .

“. . . . I remember Herbert Wright as a small boy helping his father

. . . . My sisters and I would frequently walk up Miswell Lane (in

very truth a country lane in those days where one could gather

primroses and blue and white violets) to purchase eggs and other

farm produce from Mrs Wright. It was a great treat to be allowed to

climb the ladder-staircase of the mill, all white with flour dust,

and gaze through one of the little windows, at the lovely, unspoilt

Chiltern countryside . . . . [15] All around were meadows and farm land

and, directly in front, the famous ‘goldfields’, a sheet of yellow

buttercups.”

The Mill House and its adjoining granary now form a single dwelling,

one that has been sympathetically restored and modernised by its

present owners. Some of the original fittings have been

incorporated, including internal doors (complete with their

latches), cupboard doors, wooden beams, iron brackets and a

brick-lined cellar. The cast iron pump from the granary remains,

while the old well it tapped into is hidden beneath the kitchen

floor. Outside, old bricks have been re-used in some of the paved

areas and two of the windmill’s grinding stones now make attractive

garden features.

Fig. 8.5: the miller’s

cottage

During the 1960s, when new housing was being built in the Icknield

Way area, Tring Council ensured that the sad-looking old windmill

would not be forgotten entirely by naming three new roads Windmill

Way, Mill View Road, and Fantail Lane.

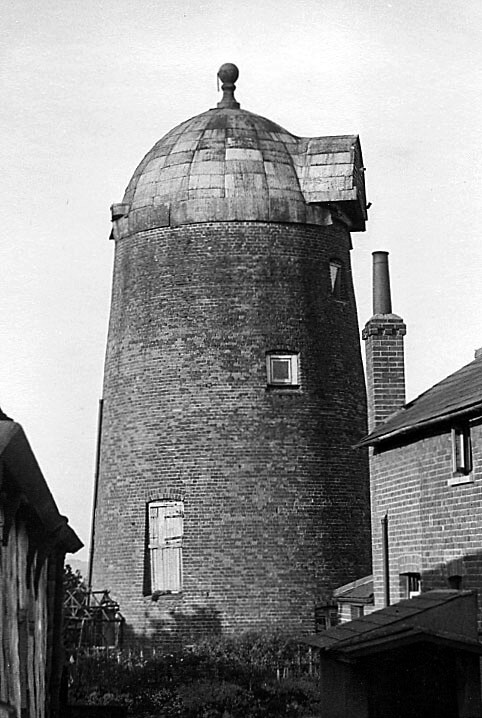

RESTORATION OF THE WINDMILL TOWER

Fig. 8.6: the mill prior to

restoration

The windmill’s fortunes improved some years later when an American

artist applied for permission to convert both the windmill and

adjacent barn to a dwelling and to add an extension to form guest

accommodation. But conversion of an old building is not a simple

matter, and this was explained in one of a series of articles

featuring unusual homes that appeared in the Post Echo of

September 1979 . . . .

“. . . . the previous owner gathered in the barns and milking sheds

which huddle around the old mill and made the whole thing into a

place of rambling spaciousness. There’s a good reason for this. A

windmill may be very stout — walls start at two and a half feet

thick at the bottom and taper to one and one and a half at the top —

and snug, but it’s a problem to put water pipes in. On outside walls

they disfigure the place: same goes for the inside walls.

So the builder left them out, which ruled out a kitchen and bathroom

in the tower . . . . The original lead cap is now an ornament in the

back garden. The man who converted the mill was so concerned with

retaining the original effect, and so unconcerned with the expense,

that he put in a glass fibre replacement, impregnated with copper

crystals. . . .”

When the windmill was again offered for sale in 2004, the sales

particulars described five circular rooms, some with the old beams

and timber cog wheels, and a tower room with spectacular views.

Goldfield windmill now claims the distinction of Grade II listing,

as well as being the only remaining tower mill in Dacorum.

Fig. 8.7: aerial view of Goldfield

Mill |